This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

The murky world of art crime

The murky world of art crime

9 Jan 2023

If you’ve ever wondered how the world of art crime works read on, as we pose key questions to Arts Society Lecturer Will Korner

How does art crime manifest itself?

The first thing that comes to mind when talking about ‘art crime’ is Hollywood-style heists from museums, yet these make up a tiny percentage of such crime. Art crime is more varied – both in terms of types and objects stolen – and can have a darker side to it, from home break-ins and high-street smash-and-grabs, to jewellery and metal thefts for their base materials, to more idealogical destruction or damage. All this comes before one also considers the historic legacy of theft and looting in times of war and unrest, including that during the period of the Nazi regime and, more recently, tales of cultural property being stolen or targeted around the world.

How does this type of crime work?

The majority of art crimes are driven by opportunism and a financial motive. A thief sees value in an artwork and tries to derive financial gain – but realising that value is more difficult than it appears. If an artwork is stolen, there is little intrinsic value, unless it is attributed to an artist and has good provenance. The only way to realise some value is to pawn off the object for a fraction of its price as an unattributed work; sell it to someone who does not know much about the work; or take a risk and try to sell it to an art dealer, or through an auction house. Even if the thief manages to find a buyer, the new owner is likely to put it up for sale publicly without knowing the object’s true history, which of course leads to the work being found.

Why are masterworks stolen when resale is impossible?

Stealing famous artworks from museums is different to thefts from private homes (which are more opportunistic). But, while thieves might plan the heist of a masterpiece from a museum, there are limited opportunities to sell it, rather than a lesser-known stolen artwork. A common misconception for both thieves and the public is that there are ‘Dr No’-style collectors desperate to have stolen masterpieces in their secret private collection. Furthermore, such thefts are almost always well publicised, and law enforcement, the art trade and the general public are usually aware and keeping an eye out for such works. While a sale is not impossible, these artworks often, sadly, end up with gangs involved in other criminal areas and may well be badly stored and held for ransom.

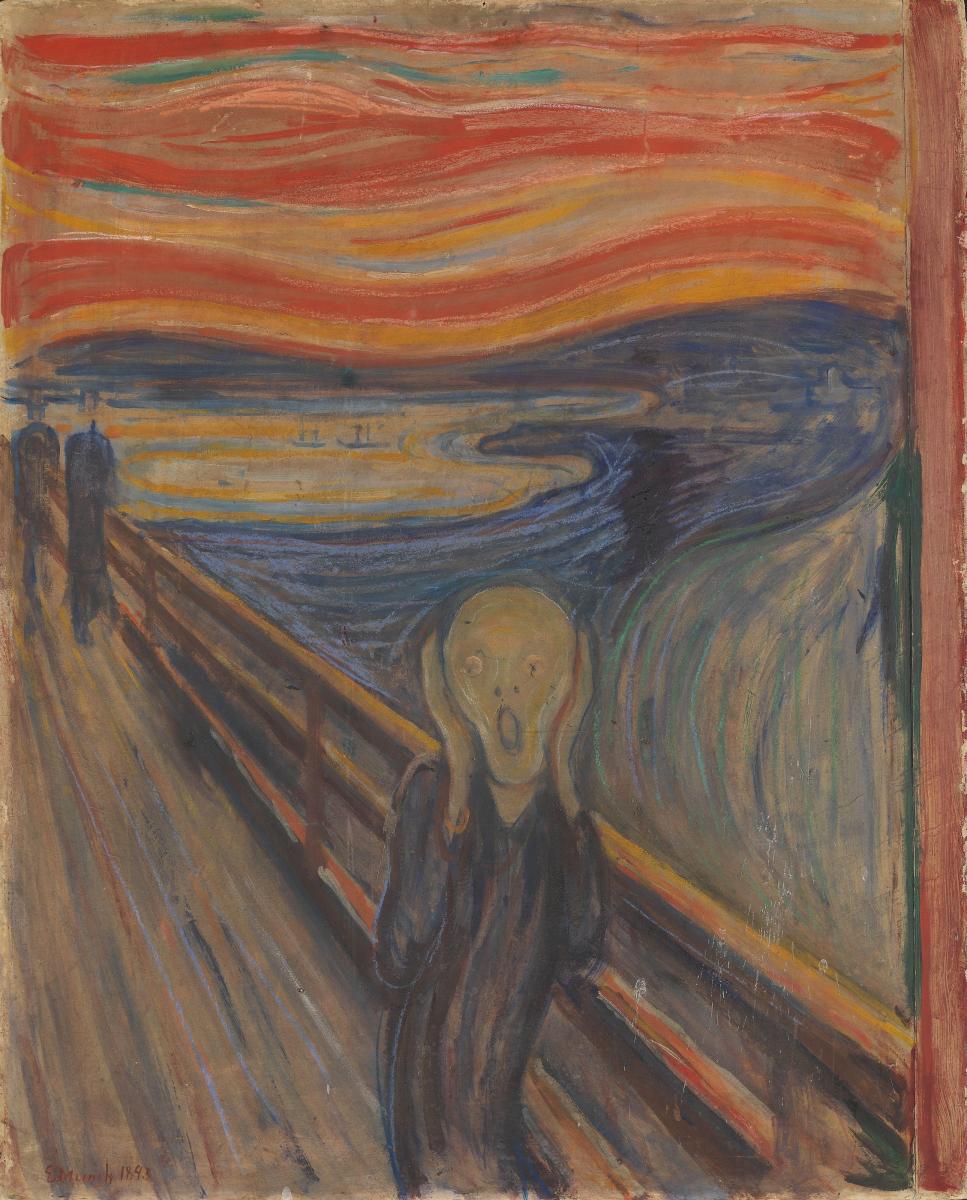

The Scream by Edvard Munch, 1893; one of Munch’s versions of this work has been stolen not once but twice. The version shown here is safely on view in the National Museum in Oslo (nasjonalmuseet.no/en ). Photo: Nasjonalmuseet/Høstland, Børre

What have been the most audacious steals of all time?

Perhaps the most infamous theft was of 13 important artworks from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston, USA in 1990, valued at some half a billion dollars. It included masterpieces by Vermeer and three works by Rembrandt.

Sadly, after 32 years, none of those artworks have ever been recovered, despite a $10m reward offered by the FBI. The frames still hang, empty, in the museum today in the hope they will one day be returned.

Beyond that theft, the 2019 heist from the Dresden Green Vault is probably the largest and most audacious of recent times. It saw precious 18th-century royal regalia, weapons and jewellery adorned with 4,300 diamonds taken – apparently to the tune of some €1bn.

In terms of famous individual paintings that are still missing, there is Caravaggio’s Nativity with St Francis and St Lawrence, stolen in Sicily in 1969; while the most famous artwork still missing from World War II is Raphael’s Portrait of a Young Man, possibly last seen in a forest in Poland in 1945.

Two of the best-known artworks in the world have been the subject of snatches; the Mona Lisa was taken from the Louvre in 1911, which had a major impact on its subsequent fame, and Munch’s The Scream (or, rather, one of the three versions of the painting) has twice been stolen in Oslo – and thankfully recovered both times.

How many treasures remain missing?

A huge number, ranging from paintings to furniture, porcelain, ancient objects, clocks, jewellery and watches, to name just a few. The main international database of stolen art, the Art Loss Register, includes more than 700,000 items reported as missing.

Is there an art crime myth that should be busted?

Apart from the ‘Dr No’ collectors myth, which has little base in fact, another common misconception is that artworks are ‘stolen to order’ – that is extremely rare. Art theft is far more often an opportunistic crime.

What legacy does art crime have?

Many see art crime as exciting or ‘white collar’ crime, and therefore harmless, but it is important to remember that much of this crime is aggressive or destructive to individuals or entire communities, leaving a long legacy.

We see that in newsfeeds on the erasure of monuments or cultural objects during war and genocide, but it is far closer to home than you might think.

Take, for example, just a few of the political events at the National Gallery alone. There was Mary Richardson’s slashing of Velázquez’s The Rokeby Venus as part of the suffrage movement in 1914; and the morally driven theft of Goya’s Duke of Wellington in 1961. There are also actions of climate protestors as recently as this year, when targeting artworks.

One overriding fact is that art crime is capable of long reach. I have worked on hundreds of cases of stolen art. Some have been financially or historically ‘higher value’ artworks. Others have been worth a few thousand or a few hundred pounds but with a deep emotional or personal connection to their former owner. Art crime, after all, can affect us all.

For more art stories

See The Arts Society Magazine, available exclusively to members and supporters of The Arts Society (to join, see theartssociety.org/member-benefits). You can also receive arts stories directly by signing up at theartssociety.org/signup

About the Author

Will Korner

Will Korner is an art crime specialist, having assisted on hundreds of cases with law enforcement, governments, cultural ministries, archaeologists and others internationally to recover stolen art and repatriate cultural property. He currently works as the global fairs project manager at TEFAF, the world’s leading art and antiques fair. He is also an Arts Society Accredited Lecturer; among his Arts Society talks are Art crime: myth and reality and The destruction and looting of cultural property – a global legacy.

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition