This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

A magical exhibition for Halloween

A magical exhibition for Halloween

25 Oct 2018

My mother was a witch, or so she said, and her affinity for associating eerie and mysterious tales with what were regarded as everyday objects fascinated me when I was a child.

Apart from the obvious, such as horseshoes and four-leaf clovers, I was alerted to the potential folkloric power of objects such as a ‘hag stone’ – a stone with a hole through it. These are viewed by some as a powerful protective amulet and a window to the fairy realm. In retrospect, I feel that my mother’s ‘supernatural’ insight largely broadened my horizons and fostered an inherent interest in what makes us ‘believe’ or ‘not believe’ in magic.

I have continued to explore this interest through objects – particularly objects imbued with a sense of myth and folklore. As a result, I was keen to see Spellbound, the Ashmolean’s exhibition which, through 180 objects, explores the centuries-old relationship between the human condition and magic, ritual and witchcraft.

Two ‘unicorn’ horns, in fact narwhal tusks, from the 13th to 15th century © New College, University of Oxford

I had some expectations: these were mainly related to items that I thought should not be omitted from the exhibition, under any circumstances. Yet, I was also aware that I was likely to be presented with objects outside of my experience, both physically and spiritually.

Arriving at the show, I was faced with a choice. A challenge. There was a ladder against the wall; this felt like an obvious way of testing every visitor’s ability to deal with the power of superstition – whether to fly in its face and gain strength from the perversity of defying its effect or, alternatively, to play safe. I walked underneath it, but I observed that most walked around it. The ladder was a minor symbol of our modern propensity for perpetuating old superstitions and, as that, it proved difficult for most people to flout.

‘Some might say that it’s easy for us “modern humans” to dismiss the mumbo-jumbo of our medieval ancestors, who were ruled by their perception of a world inhabited by spirits and demons’

The medieval manuscripts that came after were bound to startle.

Among the 15th- and 16th-century works on ‘microcosmic man’, ‘zodiac man’ and ‘planet man’ were works of contextually almost incalculable power. Some might say that it’s easy for us ‘modern humans’ to dismiss the mumbo-jumbo of our medieval ancestors, who were ruled by their perception of a world inhabited by spirits and demons, but Spellbound immediately presents some powerful material – and none more so than the censored magical volumes for raising demons such as Astaroth, the Great Duke of Hell. The missing pages and redacted words felt like the thin line between everyday normality and eternal damnation. I was mesmerised by their historic power. So, too, the sigils or Sigillum Dei (Seal of God), a talisman designed to ‘grant the operator’ the ability to ‘force spirits to appear in an attractive and docile form’.

In the same space several hundred padlocks, or ‘love locks’, from the Leeds Centenary Bridge are displayed. These padlocks are a more modern practice, whereby inscribed locks are attached to the railings of a bridge or structure and the key cast into the water. The symbolism is obvious, but why display them here? The answer is obvious too. We may have a different concept of the world around us, but the same fears still inhabit our minds: the need to be loved, our fear of evil, and the need to protect our families and homes.

Contemporary love lock on Leeds Centenary Bridge, 2016. Courtesy of Leeds City Council

In this respect, the exhibition strikes an emotional chord. It sets out these essentials in the form of inscribed medieval gold posy rings, talismans and magic squares, desiccated cats and witch bottles. There is much to identify with here; daisy wheels, the compass-drawn protective symbols that appear in many old buildings on stone, woodwork and even furniture, are represented on a 19th-century Duchampesque barn door, from Suffolk. The sculptural quality of this piece seems at home with the modern installations by contemporary artists that also feature in the exhibition. I have to admit to jumping clean out of my skin as I entered the darkness of the chimney-like space of sculptor Katharine Dowson’s Concealed Shield, unexpectedly finding myself face-to-face with another visitor.

‘I have no doubt that this was a difficult exhibition to curate, perhaps bordering on the taboo for some, yet this is what makes it all the more enticing’

Spellbound is an exhibition of some parts, but with a cohesive theme. The compelling diversity of its content is enthralling and emotive, perhaps even a little contentious. I was thrilled so see many exhibits that were loaned by my colleague on the Antiques Roadshow, Geoffrey Munn, and also to peer into Dr John Dee’s (advisor to Queen Elizabeth I) obsidian scrying mirror, an object from the British Museum, without which the exhibition would not have been complete.

I have no doubt that this was a difficult exhibition to curate, perhaps bordering on the taboo for some, yet this is what makes it all the more enticing. Perhaps it is also why my favourite object of all was not in the exhibition – a Hand of Glory (the preserved left hand of a hung felon). Whatever the case, whether you are propelled to visit on the basis of an interest in witch ducking or the ritual deposits of ancient folk custom, it may well be the power of these words that persuade you to go. I can highly recommend it.

Spellbound: Magic, Ritual & Witchcraft is at the Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology, Oxford until 6 January 2019; ashmolean.org

The other contemporary artworks in the exhibition have been created by Ackroyd & Harvey (ackroydandharvey.com) and Annie Cattrell (rca.ac.uk/more/staff/annie-cattrell/)

Human heart in heart-shaped lead and silver case. Found concealed in a niche in the pillar in the crypt beneath Christ’s Church, Cork, 12th or 13th century. 2.3 x 1.6 cm © Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford

Human heart in heart-shaped lead and silver case. Found concealed in a niche in the pillar in the crypt beneath Christ’s Church, Cork, 12th or 13th century. 2.3 x 1.6 cm © Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford

Henry Fuseli (1741–1825), The Witch and the Mandrake c. 1812, Graphite and chalk on paper, 8.7 x 6.6 cm © Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford

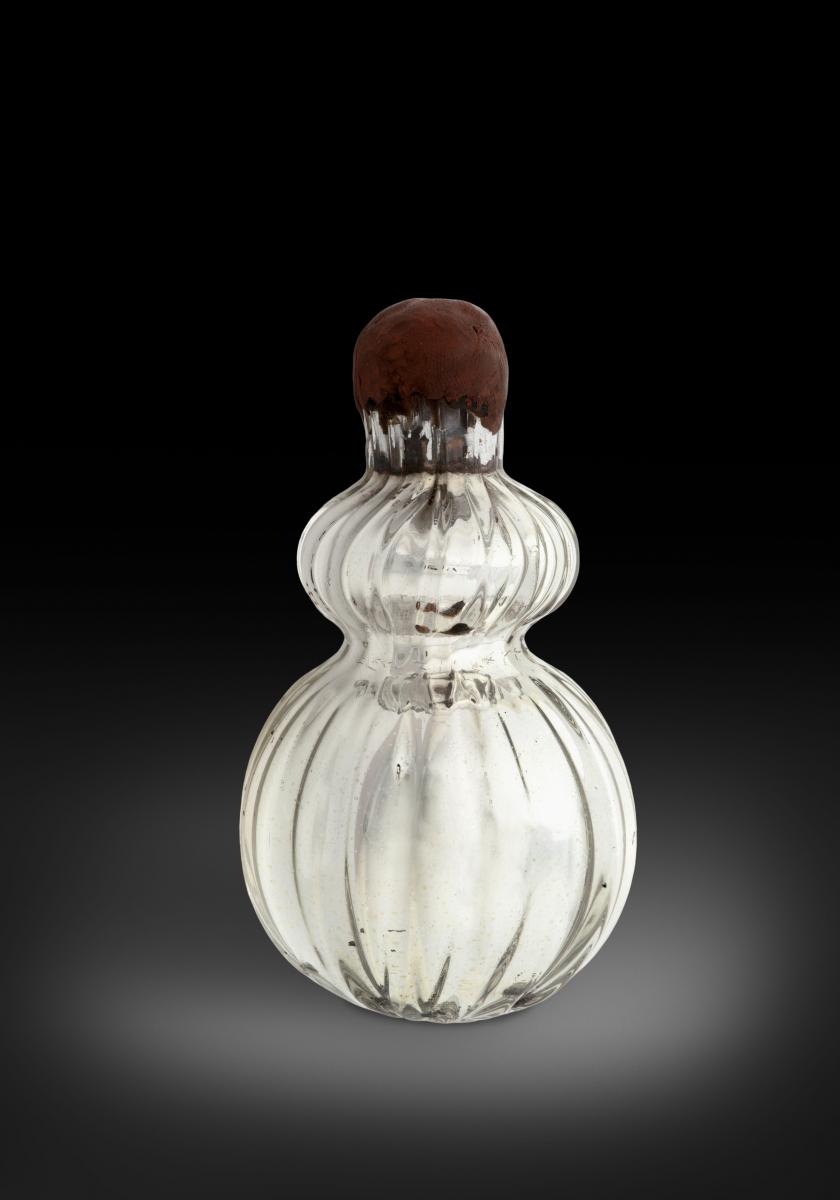

A witch trapped in a bottle, England, c. 1850, Glass, silver, cork and wax © Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford

About the Author

Marc Allum

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition