This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

The Lure of Wonderland

The Lure of Wonderland

21 May 2021

Is Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland one of the art world’s biggest influencers? As a major new exhibition explores the tale, Arts Society Lecturer Elizabeth Merry peers through the looking glass for evidence

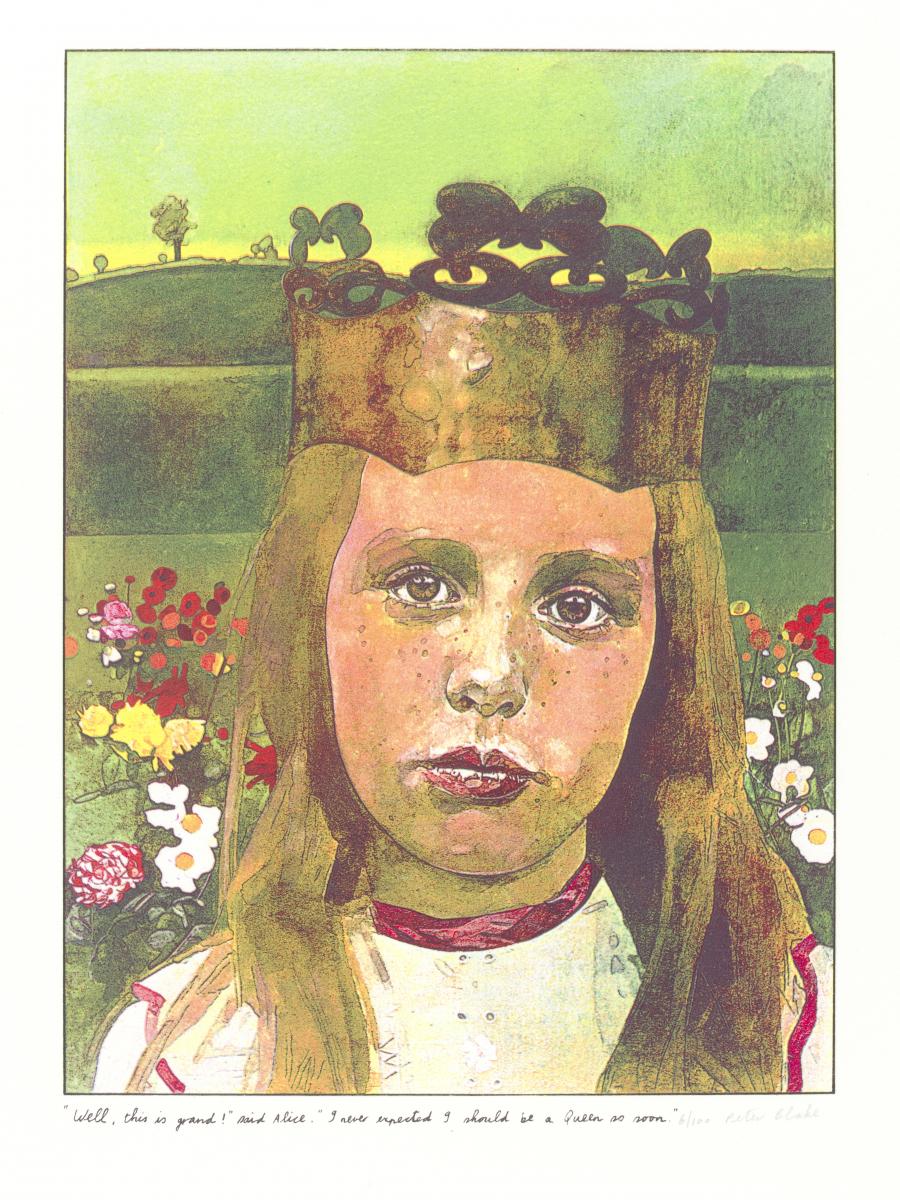

Print by Peter Blake from a suite illustrating 'Through the Looking Glass and What Alice Found There'. 1970. © Peter Blake. All rights reserved, DACS 2019

Print by Peter Blake from a suite illustrating 'Through the Looking Glass and What Alice Found There'. 1970. © Peter Blake. All rights reserved, DACS 2019

‘Curiouser and curiouser,’ says Alice, finding herself ‘opening out like the largest telescope that ever was’, after consuming a cake labelled ‘EAT ME’. Curiouser and curiouser has been the impact of Charles Lutwidge Dodgson’s two ‘Alice’ tales, written over 150 years ago to entertain and amuse young Alice Liddell. Never out of print, they’ve been translated into over 170 languages and have inspired art and sculpture, stage and screen, ballet, opera, fashion and musicals.

The first pantomime performance was in 1886; Dodgson himself was in the audience. Since then both books have undergone intense and detailed scrutiny, encompassing a gamut of disciplines and theories. These include psychoanalytical expositions ranging from sexuality and perversion to insanity and psychosis; the unpicking of perceived symbolism in Dodgson’s writing – both content and format – and a multitude of visual interpretations by a huge number of artists.

‘WHEN ALICE’S ADVENTURES IN WONDERLAND CAME OUT OF COPYRIGHT IN 1907 ARTISTS RUSHED TO GET IN ON THE ACT’

The books offer rich and fascinating resources for pictorial inspiration. The initial illustrator was Dodgson himself – not yet world famous as Lewis Carroll – a maths don at Oxford, whose original handwritten illustrated copy was his 1864 Christmas present to Alice Liddell. He planned to print it privately, providing himself with a stock of books to give away as presents. However, when Macmillan & Co agreed to publish he decided the quality of his draughtsmanship was inadequate.

Enter John Tenniel. The successful Punch cartoonist, initially reluctant, was won over by the fantasy and originality of the story. His illustrations remain the most familiar: meticulous, detailed images, which became inextricably identified with both books. There’s grotesquery aplenty, hidden caricatures of public figures of the day, and a little blonde Alice, who became both a prototype for several future illustrators, and a model for performance adaptations of the tales. For many people still, Tenniel’s pictures are as integral to the books as Dodgson’s narratives.

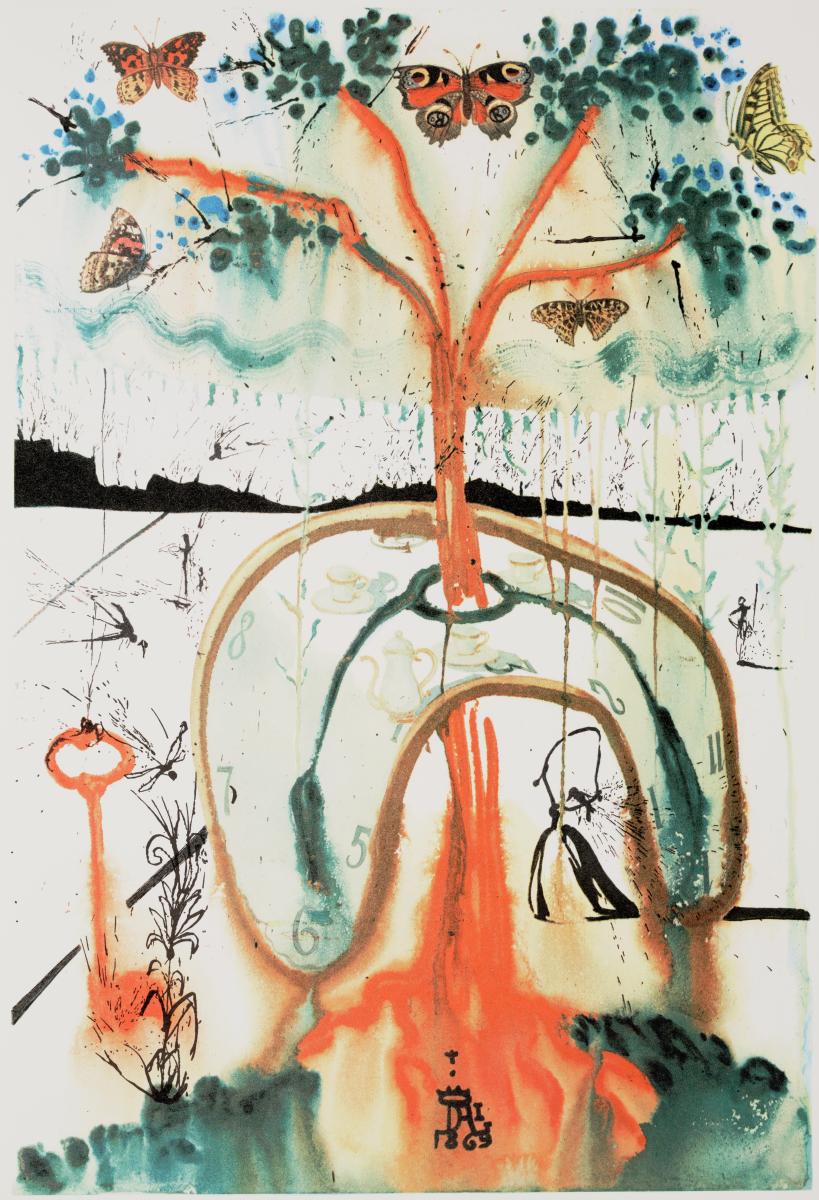

Salvador Dali, A Mad Tea Party, 1969, © Salvador Dali, Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, DACS 2019

Salvador Dali, A Mad Tea Party, 1969, © Salvador Dali, Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, DACS 2019

THROUGH THE GLASS

When Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland came out of copyright in 1907 artists rushed to get in on the act. Trawling through some of these early-20th-century illustrators provides a fascinating glimpse into the artistic trends of the time, with insights into the styles and preoccupations of their creators. Arthur Rackham, already established as a children’s illustrator, portrayed an Edwardian Alice. Older than her Tenniel predecessor, she is calm and composed despite Rackham’s disturbing world of gloomy woods, gnarled trees and strange, scary creatures. Rackham glances back at the Pre-Raphaelites, but is also influenced by Art Nouveau. His style, however, is very much his own – imaginative, complex images invoking the darker fantasies of traditional folklore.

Rackham’s contemporary, Charles Robinson (brother of William Heath Robinson) was another early illustrator. He produced accomplished drawings owing something to the aesthetic Art Nouveau works of Aubrey Beardsley. Robinson’s pictures contrast large areas of black and white with intricate detail and fine line; like Beardsley, he designed them in full-page layout with decorations bursting out of the frame.

Anna Gaskell, Override#25 (Override), Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum © courtesy of Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne

Anna Gaskell, Override#25 (Override), Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum © courtesy of Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne

Even before copyright ran out, the first Alice in Wonderland film arrived, all nine minutes of it, galloping through incidents in the story and starring 18-year-old actress May Clark as a rather mature Alice. Since then there have been some 40 more, including Walt Disney’s 1951 cartoon – a ‘feel-good’ movie to brighten up post-war austerity – and Jonathan Miller’s 1966 BBC version, which he described as: ‘A Victorian fantasy about the perils and pains of growing up.’ Miller’s Alice is a serious, fey child, verging on puberty, drifting through a series of surreal, Neo-Gothic set pieces and encountering odd people, for Miller’s animals are eccentric Victorian grown-ups.

As the century advanced, child psychology moved centre stage. Hitherto uncritical admiration of the books yielded to some disturbing suggestions, notably Dodgson’s perceived obsession with little girls. A few illustrators of the 1940s reveal some unease in their pictures. Mervyn Peake, creator of the Gormenghast trilogy, produced his Alice illustrations in the post-war years. His grinning Cheshire cat is terrifying; Alice looks anxious and fearful. Peake suffered a nervous breakdown during the war; for him Alice’s dream was like a nightmare.

Zenaida Yanowsky as The Red Queen in Christopher Wheeldon's ballet Alice's Adventures in Wonderland. The Royal Ballet. ©ROH, Johan Persson, 2011. Sets and costumes by Bob Crowley

LAND OF DREAMS

Dreams are fundamental to Surrealism, exploring through art the realms of the subconscious, irrational and imaginary. Painter Dorothea Tanning and her lover then husband, Max Ernst, produced pictures influenced by Alice. In Tanning’s 1943 Eine Kleine Nachtmusik the background is a set of doors – portals to the unknown – mirroring Alice’s arrivals in that series of strange settings in Wonderland. Ernst created artworks reflecting the illusory imagery of the looking glass, also displacement and escape (he had once been on the run from the Gestapo). And Salvador Dalí’s 1969 work, A Mad Tea Party, shows the familiar Dalinian melting clock as a tea table – depicting the mastery of time and how it devours itself and everything else; no time for tea, because everyone has to keep moving round the table.

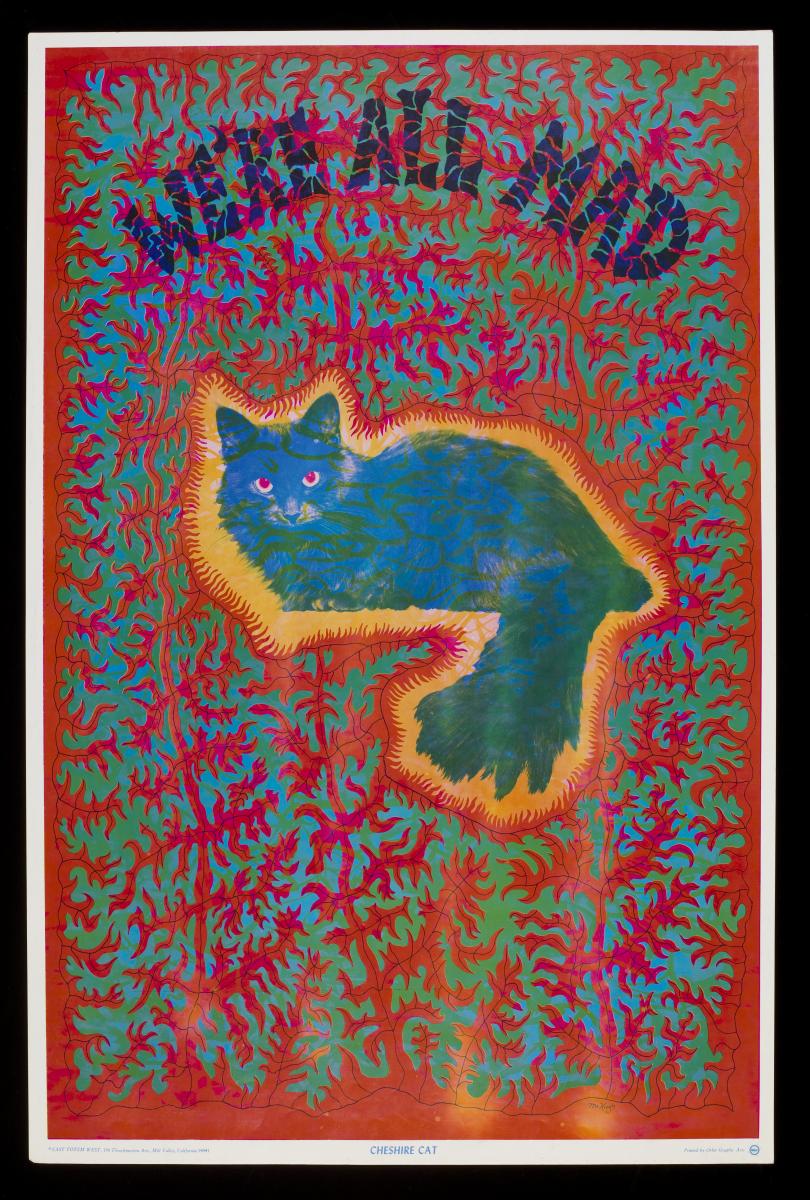

'Cheshire cat', psychedelic poster by Joseph McHugh, published by East Totem West. USA, 1967. Purchased through the Julie and Robert Breckman Print Fund. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

'Cheshire cat', psychedelic poster by Joseph McHugh, published by East Totem West. USA, 1967. Purchased through the Julie and Robert Breckman Print Fund. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Back to realism, social and political cartoonist Ralph Steadman turned his attention to Dodgson’s text in 1967. His pictures are audacious and dynamic – a contemporary spin on the social satire of the original – with the White Rabbit as an irate commuter with bowler hat and umbrella. During the 1960s, decade of flower power and the summer of love, Alice’s dream adventures converted her into a hippy-trippy icon. Joseph McHugh’s psychedelic Cheshire cat poster, Jefferson Airplane’s song White Rabbit and the Beatles’ I am the Walrus all draw on Dodgson’s stories. The Beatles deemed him such an important influence that he’s among the faces on Peter Blake’s 1967 photo- montage sleeve for Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. Blake himself created a set of screen prints in 1970 for new editions of both books.

Today Alice continues to fascinate. Just some of the current artists who’ve produced their own interpretations include rapper P Diddy, author and illustrator Anthony Browne, artists Maggie Taylor, Nalini Malani and Annalies Štrba, and photographers Annie Leibovitz and Tim Walker. The latter’s 2018 Pirelli calendar recreated Wonderland with an all-black cast including drag artist RuPaul and Naomi Campbell. Seemingly, this little girl, intelligent and rational, self-questioning and brave, wasn’t just revolutionary in her own era, but has become an icon for all time.

OUR EXPERT’S STORY

• Elizabeth has more than 35 years’ experience lecturing at universities, summer schools, literary societies and museums, and has been an Arts Society Lecturer for over 10 years • She is fascinated by the links between the different branches of the arts, the social and cultural trends underpinning them and how they influence one another

• Among the talks she gives is Illustrating Alice – some views of Wonderland

SEE

Alice: Curiouser and Curiouser

Opens 22 May at the V&A

This feature first appeared in the summer 2020 edition of The Arts Society Magazine, available exclusively to Members and Supporters

About the Author

Elizabeth Merry

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition