This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

Leading light: Dr Chila Kumari Singh Burman

Leading light: Dr Chila Kumari Singh Burman

9 Apr 2021

Agnish Ray speaks to the acclaimed artist about the beauty of everyday objects, illuminating Tate Britain and reclaiming the streets

The artist in front of her installation at Tate Britain. Photo: © Tate 2020/Joe Humphrys

The artist in front of her installation at Tate Britain. Photo: © Tate 2020/Joe Humphrys

Hanging on the wall behind Dr Chila Kumari Singh Burman, as she speaks to me from her north London home, is what looks like an ornate print, with birds, butterflies and flowers scattered across a field of shimmering gold. I wonder if the work is one of the artist’s own creations, but she informs me it is just a piece of wrapping paper.

Don’t knock it just yet. Recycling everyday objects like this was fundamental to the Arte Povera Movement that emerged in the 1960s, and Burman applies the same philosophy by finding meaning in simple, ubiquitous items like flowers, kitsch jewellery and cheap accessories. ‘All my junk,’ as she puts it.

Winter Commission/ Chila Kumari Singh Burman. Photo: © Tate (Joe Humphrys)

Winter Commission/ Chila Kumari Singh Burman. Photo: © Tate (Joe Humphrys)

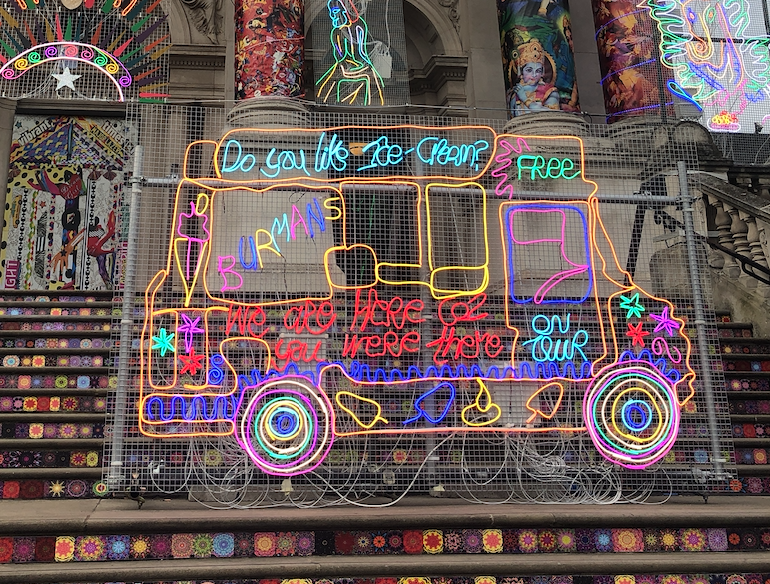

With a career spanning four decades of printmaking, painting, photography and even a dabble in punk rock, Burman is currently sought after by the likes of the Museum of the Home (formerly the Geffrye Museum) in London and the dynastic Jindal family in Mumbai. Late last year, her installation for Tate Britain’s Winter Commission – occupying the facade of the building – swapped Christmas for Diwali, featuring Hindu deities, fireworks, peacocks and a fluorescent ice-cream van. As the country went into its second, and then third, lockdown, the work conveyed a powerful message of hope amid the darkness, in the true spirit of the Hindu festival of lights.

Fans of Burman’s work may have recognised the wacky auto rickshaw adorned with objects like rakhis, bindis, plastic eyelashes and Swarovski gems – before Tate, there was a similar one displayed at the Science Museum’s Illuminating India exhibition in 2017. More recently, Netflix viewers may have spotted the artist’s blinged-up SUV in the new film The White Tiger, which tells the story of a young entrepreneur fighting class and caste inequality, in a rags-to-riches journey with dark and violent consequences.

Installation detail. Photo: © Holly Black

Installation detail. Photo: © Holly Black

The tale of The White Tiger struck a chord with Burman because it reminded her of her father’s own entrepreneurial trajectory, which took him from Punjab to Liverpool. Like so many Indian immigrants of his generation living in Britain, Burman’s father was a self-made man. His business-savvy spirit reflected those emerging from colonisation with a sense of freedom and a vision for upward mobility.

There were few Indians around while Burman was growing up in Merseyside. ‘I was the only Indian girl in school,’ she tells me. ‘Whenever my dad saw an Indian person at a bus stop, he’d tell them to come over to the house for dinner.’ Yet Burman recalls little racism back then. On the contrary, communities from different backgrounds supported each other. ‘The street brought us up,’ the artist explains. ‘My mum had arrived from India with three kids and she couldn’t speak English. The working-class families of Liverpool took us under their wing.’

Courtesy Netflix

Courtesy Netflix

It was later, in her university days, that race became an unavoidable issue. Following a wave of immigration from countries that were part of Britain’s colonial rule, people of colour were suddenly the subject of contempt in the UK. Burman became involved with various black and Asian activist groups opposing racism in Britain, moving in circles with artists like Eddie Chambers, Claudette Johnson, Marlene Smith and Keith Piper.

‘MY MUM HAD ARRIVED FROM INDIA WITH THREE KIDS AND SHE COULDN’T SPEAK ENGLISH. THE WORKING-CLASS FAMILIES OF LIVERPOOL TOOK US UNDER THEIR WING.’

Now, as the artist prepares a new public art commission for Covent Garden’s West Piazza, her spirit of activism is more alive than ever. Expect neons, collages, text and bright colours: ‘Punjabi hits meets Bollywood meets a Hindu temple,’ she says. The installation is planned for September, when the streets might once again be full of people to admire it.

As the pandemic has taught us, a lot can happen in a year, and if Burman’s Tate installation captured a mood from the time, the work she is preparing for autumn must reflect a new world. However, it may not be the post-pandemic utopia that so many are dreaming of. On the contrary, other urgent and troubling concerns have arisen this year, following the murder of Sarah Everard in London and the findings on violence against women in the UK that since emerged.

Installation detail. Photo: © Holly Black

Burman is no stranger to tackling difficult subjects head-on. In 1976, she helped set up an Asian women’s refuge in Chapeltown, Leeds. The following year, she took part in the Reclaim the Night march organised in response to the Yorkshire Ripper murders. In 1981, she created a work in protest against police brutality during the uprisings in Brixton, close to where she was living at the time. All these years later, similar subjects seem to be resurging, and the public safety of women is, again, an unavoidable subject.

‘I want to say something about what’s happening right now,’ says Burman, who used to live on Poynders Road, the spot in south London where Everard was last sighted before her murder this March. ‘I can’t not,’ she continues. ‘It’s too close to my heart.’ A public installation in one of London’s most iconic squares is, after all, yet another chance to reclaim the streets.

Read more about Dr Chila Kumari Singh Burman in the spring issue of The Arts Society Magazine, available exclusively to Members and Supporters.

Agnish Ray is a freelancer writer based in Madrid

About the Author

Agnish Ray

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition