This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

An interview with artist Linder Sterling

An interview with artist Linder Sterling

26 Mar 2018

In an exclusive Q&A with Sue Herdman, editor-in-chief of The Arts Society Magazine, post-punk artist Linder Sterling talks about her Chatsworth House residency, feminism and bellringing.

Photo: Emile Holba. Linder, as an homage, wrapped in fabric that she designed for the fashion designer Richard Nicoll, with whom she collaborated and who died, aged 39, in 2016. She hopes to feature an aspect of their collaboration in the Nottingham Contemporary exhibition.

Known for her influential work in collage, the artist (often known simply as Linder) first came to attention in 1977 when she created the cover art for punk band Buzzcock’s single ‘Orgasm Addict’. Since then, her work has been exhibited nationally and internationally. Five of her pieces are in the Tate, and last year she was a recipient of the UK’s largest art prize, the Paul Hamlyn Foundation Award.

Over the past six months, Linder has been the first artist-in-residence at Chatsworth House. You can see the resulting exhibition Her Grace Land at Chatsworth from 24 March until 21 October 2018 – and a major retrospective of her art, The House of Fame, at Nottingham Contemporary from 24 March until 24 June. Here, Linder talks charm, menace, feminism and rummaging through the attics at Chatsworth House.

How would you describe your art?

I work, in the main, in collage; sourcing found photographs dating from the early 20th century to the present day. With those images, I utilise the technique of photomontage, creating new imagery and fresh meanings that are distinct from the source material. The montages, in turn, are frequently incorporated within other disciplines, including ballet, performance, film, interior design, even cosmetics. My work has been described as carrying both charm and menace; some of the images I use are taken from pornographic magazines, others from fashion or interiors and domestic publications.

It sounds as if you’ve been creating a type of collage of Chatsworth itself?

The body of work is of different parts. I have made new collages; one is based on a portrait of Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, who died in 1806; and one is of her friend, Lady Elizabeth Foster, with whom she lived in a curious ménage à trois with the Duke of Devonshire.

I’ve also been making a new bank of images, which will be a resource for future photomontages. I’ve created a film, based on the relationship between Chatsworth’s founder, Bess of Hardwick, and the captive she watched over for years: Mary, Queen of Scots. I’m interested in the embroideries that they worked on together, which included symbols of critique, such as a cat with fur the colour of Elizabeth I’s hair. The subversive stitch will always fascinate me.

Working with Chatsworth’s gardeners, we’ve harvested larch turpentine to create an incense based on the woods. I like the idea of bringing the garden into the house – creating olfactory portraits and landscapes within the house with the incense, which is, itself, a form of collage. Working across a range of senses, I can – now that the residency is complete – send ‘biopsies’ of Chatsworth’s sights, sights and aromatics all over the world.

Does sound play its part in this body of work?

I’ve collaborated with my son, Maxwell Sterling, who is a film composer. He has been capturing oral histories from the people here, and weaving them with sounds from Chatsworth. With these we have made a sonic cadavres exquis for the Sculpture Gallery.

We’ve also worked with local bellringers: at Midsummer, a bell symphony will take place with all the church bells on the estate ringing at once, along with hand bells ringing out in the gardens. It should be quite a moment.

Have any particular spaces at Chatsworth fired your imagination?

I love the attics. The rest of the world falls away up there. Even the indefatigable curatorial team can’t be sure of the background stories of some of the pieces, so we spin suppositions as we pick spiders’ webs from our faces.

You’ve also been curating your exhibition at Nottingham Contemporary. Tell us more…

It is a retrospective of my 40-year practice and will feature some 100 works by more than 50 figures who have influenced my work. I’ve called it The House of Fame – a steal from the title of a Ben Jonson masque from 1609. Jonson, in turn, stole the title from Chaucer’s poem of the same name from approximately 1380. The four galleries at Nottingham Contemporary will each be imagined as a house within The House of Fame.

You want overlooked female artists to be placed to the fore in the show. Who are they?

I’ve included textile works by the Swedish artist Moki Cherry, which have never been seen in the UK before. I was aware of her in the late 1970s, via her husband, the jazz musician Don Cherry. He incorporated Moki’s textiles in his performances, album sleeves and poster design. I saw a small retrospective of her work at Moderna Museet last year and was struck by its vibrancy and reach.

Surrealism will always hold me in its thrall and I’ve been researching the life and practice of the Surrealist Ithell Colquhoun. Colquhoun lived in Cornwall from the mid-1950s until her death in 1985. Two of her paintings will be included in the exhibition, as will a work by another Surrealist, Marion Adnams.

Other women whose work will also feature are Isabel A Cowper, the first female official photographer at the V&A and the Swiss avant-garde artist Heidi Bucher.

As a feminist, will you be drawing on the 2018 anniversary of The Act of Representation of the People?

As part of Glasgow International festival 2018, the Glasgow Women’s Library has commissioned me to create its inaugural ‘film and flag’ in April. The flag will be unfurled at dawn on the first day of the festival and the film will be looped within an alcove in the library all year.

I’ve also been a part of Art on the Underground’s commissions for female artists, including Heather Phillipson, Geta Brătescu, Marie Jacotey and Njideka Akunyili Crosby, as well as myself. I have been invited to design a cover for the London Underground map, which is something that I’ve always wanted to do.

I’ll also be working on an ambitious commission for Southwark tube station, which is doubly exciting now that I know that the interior is based on Friedrich Schinkel’s stage set for the Arrival of the Queen of the Night for Mozart’s Magic Flute.

You are a recent recipient of the Paul Hamlyn Foundation Award: what does this represent for you?

It’s too early to describe the contours of the creative possibilities ahead, especially being in the midst of the residency here, which is already taking my work to a far larger scale. The Paul Hamlyn Foundation Award will allow my inner Busby Berkeley to surface over the next few years, though.

When you went to art school in 1973, you were the only member of your family who had received an education beyond the age of 14. What would you like to see happen to enable more young people to pursue a career in the arts?

When I went to art school my parents were both proud and very protective of me. They’d survived grotesque poverty as children and they were determined that their own offspring would never come anywhere close to the same dire economics. They wanted me to have ‘a trade in my hands’, so I opted to study graphic design rather than fine art.

I think that the world we live in is becoming economically and socially precarious in so many ways; a lot of young people are shying away from careers in the arts. I’d love to see galleries and museums reaching out to schools and colleges even more, so that the role of the artist becomes as legible as that of a plumber.

What have been your key influences – and why?

Surrealism, feminism, glamour – they all have to do with skewing perceptions of the everyday. Women who ‘threw a glamour’ were often accused of witchcraft and subsequently hanged, so I never approach the subject lightly.

Finally, what’s next?

A solo show at Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge in 2019, and after that, more unpredictability, I hope!

Look out for the full profile feature on Linder Sterling in The Arts Society Magazine spring 2018. Follow Linder on Instagram @lindersterling for more of her work.

Images:

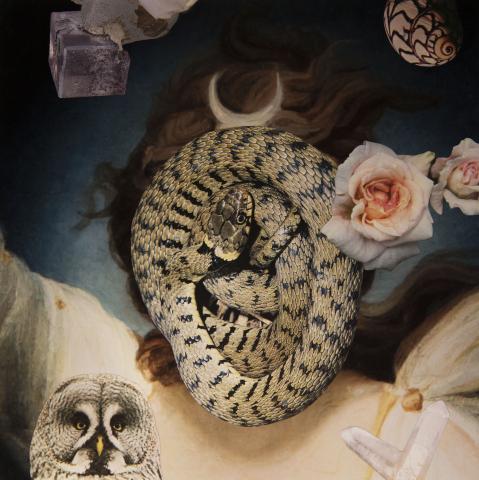

Untitled, 2018, courtesy of the artist and Stuart Shave/Modern Art. Devonshire Collection, Chatsworth

Untitled, 2017, courtesy of the artist and Stuart Shave/Modern Art. Devonshire Collection, Chatsworth

Chatsworth House Trust

About the Author

Sue Herdman

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition