This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

Five beginnings for the new year

Five beginnings for the new year

30 Dec 2022

As 2023 starts, Ciaran Sneddon explores five artworks that each showcase a different kind of fresh beginning

We welcome 2023 and the first days of a new revolution around the sun. Though the day itself may seem an arbitrary place to launch a new year – coming, as it does, in the middle of a season – it is often used as the hook, the launch pad, the inspiration for a change of tack.

Resolutions may not last forever, but new beginnings can set the course for years to come. In honour of the new year, we present five artworks that show how a fresh start can lead to all sorts of end results.

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

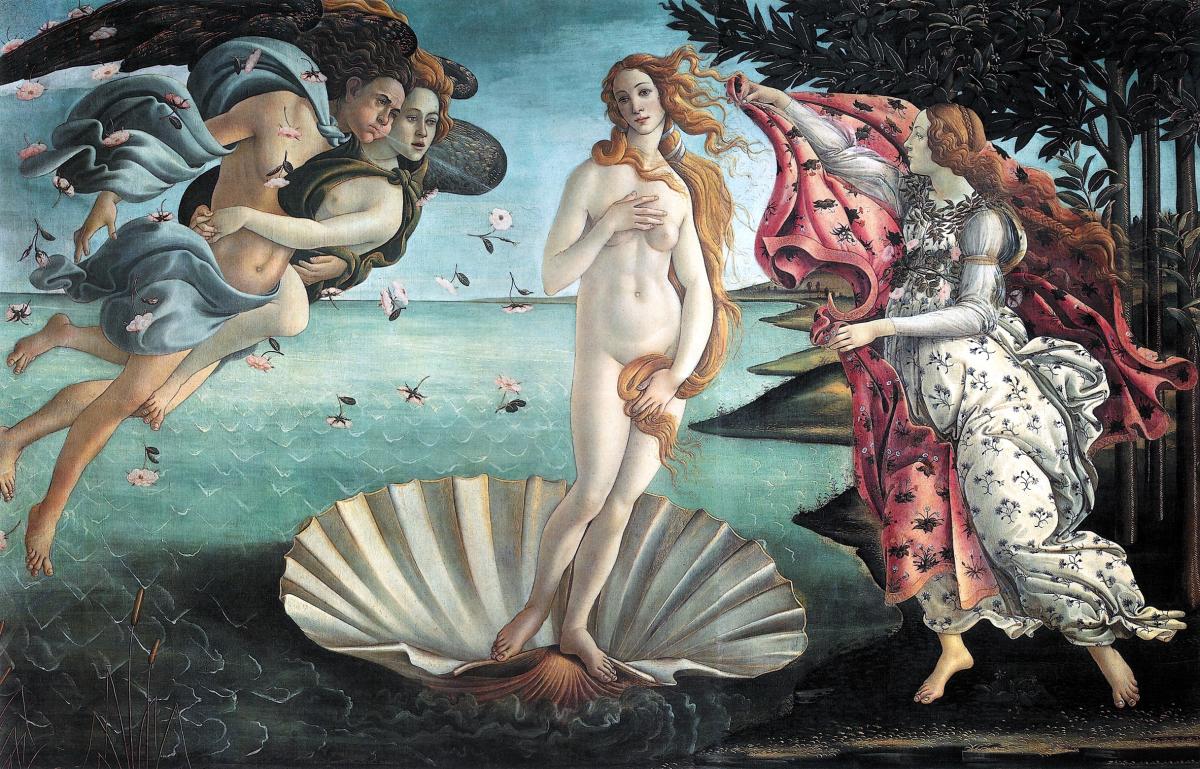

Birthing beauty

Here it is, then, the most famous painting of a new beginning – or newborn – ever put to canvas: The Birth of Venus by Sandro Botticelli, c.1480s. In a Gothic and Greco-Roman style, it depicts the arrival of Venus to shore. According to the legend, the Roman goddess of love, beauty, sex and fertility emerged from the sea as a fully grown adult. Various iterations of her origins exist, and this particular take is rooted in Venus Anadyomene (the Greek word meaning ‘rising from the sea’), which includes the scallop shell seen here.

While there are improbabilities and impossibilities in the work – Venus’s body shape and position would not survive if real-world physics were at play – it moves beyond any need for realism. Indeed, it even evades the need for overt analysis: its victories are obvious, and its story easy to unpick. If anything, the unadulterated grandeur of the image is what has allowed it to endure; the original canvas is a healthy 173 x 279cm in size.

Smithsonian/Gift of Charles Lang Freer, c.1806–11

Smithsonian/Gift of Charles Lang Freer, c.1806–11

Japanese rituals

This print duo from the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Asian Art demonstrates two new year traditions from Japan. Titled New Year Custom: Makeup on the New Year Morning and New Year Custom: Wish for a New Year’s Auspicious Dream, they were painted by Katsushika Hokusai. The artist was best known for playing a pivotal role in turning the ukiyo-e art form from one that only depicted certain officials and performers to one that could showcase wildlife and landscapes.

The first print is of a woman cleansing herself of evil spirits, while the second woman is fixing an image of the Seven Gods of Good Fortune to her pillow, so that she might have a successful new year. It’s thought that the panels were produced in the early 1800s, placing them some two or three decades before the high point of Hokusai’s career: Under the Wave off Kanagawa.

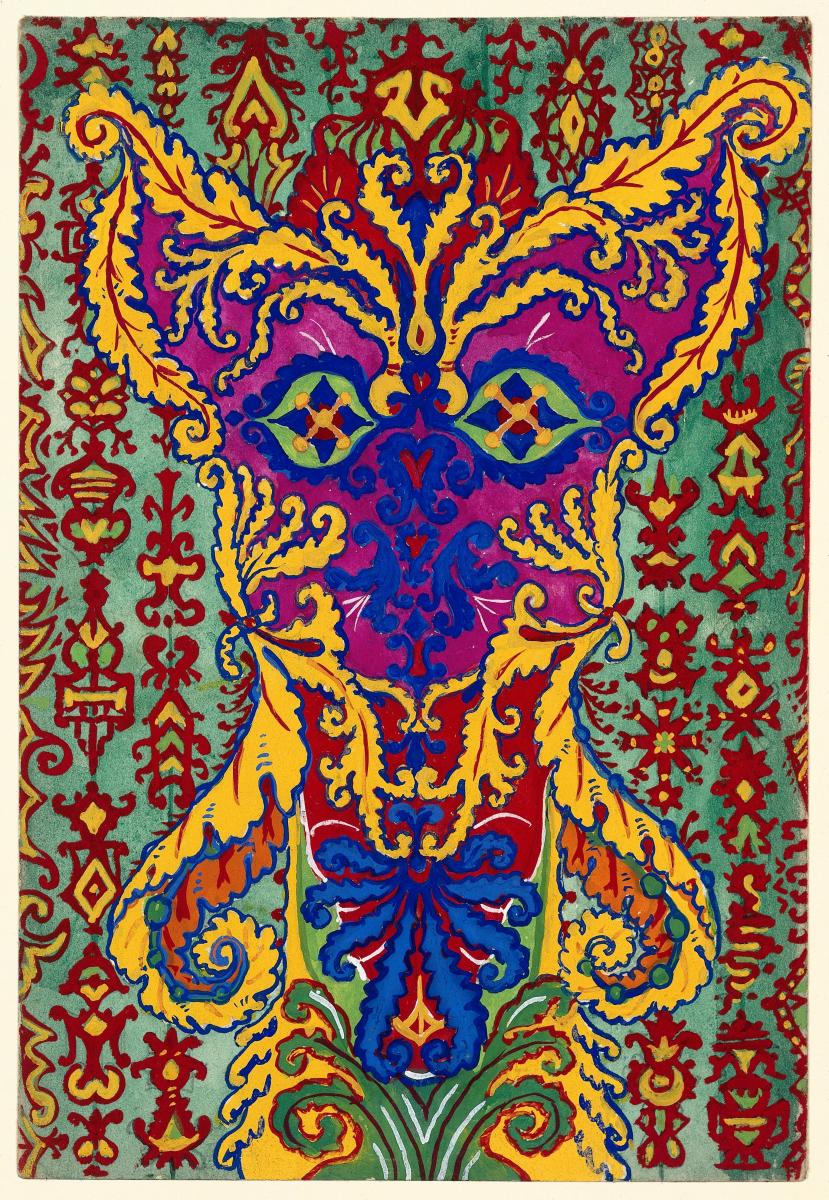

A cat standing on its hind legs, formed by patterns supposed to be in the ‘Early Greek’ style, by Louis Wain, c.1925-39. Image: Wellcome Library

A cat standing on its hind legs, formed by patterns supposed to be in the ‘Early Greek’ style, by Louis Wain, c.1925-39. Image: Wellcome Library

New directions

Louis Wain, in many ways, had a career with one constant: cats. Over the course of his lifetime (1860–1939), he dug his claws into the painting of anthropomorphised felines and refused to let go.

The earliest of these cats were cartoonish and depicted going about everyday human tasks. However, after the death of his wife, Wain began to use increasingly abstract techniques, as seen in this image. While some believe this is proof that Wain had schizophrenia, others argue this diagnosis is wrong and that he was simply trying new styles. He was committed to a hospital on the basis of erratic behaviour, and his final years were spent drawing cats and other animals for pleasure.

The Statue of Liberty by Gustave Eiffel, Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi and Richard Morris Hunt, 1886

The Statue of Liberty by Gustave Eiffel, Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi and Richard Morris Hunt, 1886

Fresh starts

Arguably the most iconic statue of all time, at some 93 metres high, Lady Liberty has become an unshakeable symbol of New York and the United States. With a goal of designing the sculpture in time for the centennial of the Declaration of Independence in 1876, it was actually dedicated in 1886, representing the hopes and values of a new nation. With its position above New York Harbour, it has gazed down on millions of arrivals to the nation, hoping to start a new life.

While the Statue of Liberty unarguably looks forward to the future, in terms of design she is rooted firmly in history. Her iconography evokes several ancient figures, including Isis of Egypt, the Virgin Mary of Christianity and Columbia of the Romans. The other representations are all too clear: a torch for enlightenment, the seven spikes on her crown representing seven continents, a tablet for the laws of a new nation, and the broken shackles at her feet showing freedom from oppression.

National Gallery of Art/Phillips Family Fund

National Gallery of Art/Phillips Family Fund

Dawn views

What better beginning than dawn itself? This is Dawn Landscape with Classical Ruins, by Jean-Baptiste Lallemand, c.1760s. Lallemand, or Lallemant as he sometimes called himself, painted sumptuous landscapes with delicate colours. The French artist never hit dizzying heights of success, but his portfolio – much of which is contained in the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Dijon in the east of France – makes for inspiring viewing.

This particular piece (from the collection of the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC) features an unidentified location harkening back, perhaps, to Babylon or a similar ancient city. The muddy tones of the bottom left contrast with the sky blue of the top right, which itself merges into the darker blues of the river. Given the natural beauty of dawn, it is little surprise that Lallemand and countless other artists have turned to its soft colours for inspiration.

About the Author

Ciaran Sneddon

Ciaran Sneddon writes for The Arts Society

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition