This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

Curator's Choice: Enchanted Interiors of the Gilded Cage

Curator's Choice: Enchanted Interiors of the Gilded Cage

30 Apr 2020

We are all experiencing an unusual period of enclosure at this time, but the idea of women being trapped in a domestic setting is far from new. One particular subject has caught the imagination of artists for centuries – that of the ‘gilded cage’, where women find themselves trapped in a luxurious yet restricted environment.

Guildhall Art Gallery explores this theme throughout history in the exhibition The Enchanted Interior, presenting works from the Pre-Raphaelite Movement to contemporary feminist interpretations. Gallery curator Katherine Pearce has selected five of its highlights, and reveal their stories.

Evelyn De Morgan (1855–1919), The Gilded Cage, 1900–19

© De Morgan Collection, courtesy of the De Morgan Foundation

© De Morgan Collection, courtesy of the De Morgan Foundation

Evelyn De Morgan was a painter of the late Pre-Raphaelite Movement and a passionate supporter of women’s suffrage, clearly reflected in this painting of a woman yearning for freedom.

The young wife of an older man is shown longing for escape into the revelry of the outside world. Her jewellery has been abandoned on the floor, showing that she refuses to value material wealth over independence. Victorian audiences would have recognised the metaphor of the ‘gilded cage’ (made literal in the top-right corner) as relevant to contemporary women, not as a relic of some distant medieval past.

De Morgan knew the importance of creativity and independence from a young age, writing: ‘No one shall drag me out with a halter round my neck to sell me!’ She married fellow artist and ceramicist William De Morgan, who shared her views on equality, and they established a collaborative relationship.

Ethel Sands (1873–1962), Interior with Mirror and Fireplace, early 20thcentury

Guildhall Art Gallery, City of London

Guildhall Art Gallery, City of London

American-born Ethel Sands was at the centre of artistic society in early-20th-century London. She was forbidden from joining the Camden Town Group by its founder, Walter Sickert, because she was a woman. He was hostile towards her depiction of elegant interiors.

However, Sands continued to use the highly decorative spaces of her home as subject matter, rendering quaint interiors sites of subtle rebellion. She lived with her life-partner, artist Anna Hope Hudson; the unseen presence of their relationship also renders such scenes quietly subversive.

As a wealthy unmarried woman, Sands was able to own her own property. Paintings such as this show the pleasure and attentiveness with which she pictured every detail of her space, where she could indulge her interests, exercise her mind and conduct her private life.

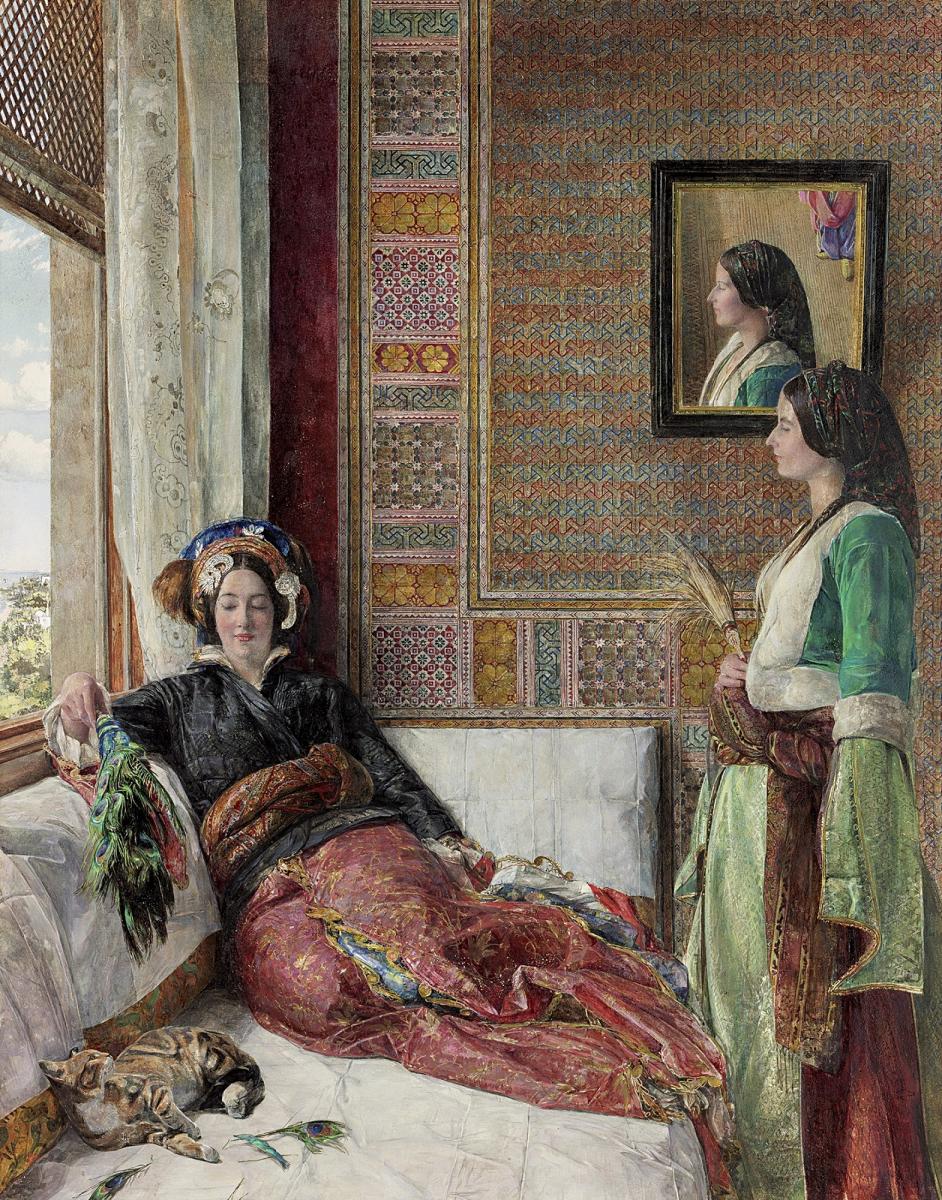

John Frederick Lewis (1804–76), Hareem Life, Constantinople, 1857

© Laing Art Gallery

© Laing Art Gallery

The harem was a favourite subject of the Orientalists, promising a glimpse into a forbidden space that fascinated Victorian audiences. Unlike many artists who never visited the places they claimed to depict, Lewis lived in Egypt for nearly a decade.

However, his paintings are ‘a harem of the mind’. The setting is a studio reconstruction, using materials and costumes that he acquired on his travels. His models were white European women. In this case, his wife, Marian, plays the role of the standing attendant. The details of the interior also have European references, such as the wall decoration inspired by the ceramic tiles of the Alhambra Palace in Granada in southern Spain.

The work tells us more about Victorian values and tastes than it does about life in the harem, but it does draw a parallel between the constrained lives of women in his constructed setting and the Victorian middle-class home, highlighting similarly patriarchal societies.

Sir George Frampton RA (1860–1928), Lamia, 1899–1900

© Royal Academy of Arts, London

© Royal Academy of Arts, London

This sculpture is based on the mythic figure Lamia as she appears in John Keats’ poem of 1820: a tragic half-serpent creature that assumes female form to win the love of a mortal, but vanishes when her true nature is revealed. In only depicting her bust, Frampton leaves her mysterious lower half to the viewer’s imagination. The large opal symbolises misfortune, and the severe headdress suggests that Lamia is a prisoner of her fate.

Her remarkable presence caused a sensation when the sculpture was first shown at the Royal Academy in 1900. She was said to have caused ‘a silence in the room’ and still has the power to enchant. Frampton’s Lamia is a figure of dualities; her face is uncannily life-like, yet also reminiscent of a death mask. Viewers may struggle to place her date of creation. She sits at the threshold of modernity to become a timeless figure, forever on the verge of transformation.

Martha Rosler, First Lady (Pat Nixon), from series House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home, 1967–72

Courtesy the artist and Galerie Nagel Draxler, Berlin/Cologne

Courtesy the artist and Galerie Nagel Draxler, Berlin/Cologne

American photographer Martha Rosler has been at the forefront of the feminist art movement since the 1970s. Her House Beautiful series collaged scenes from glossy interior design magazines with documentary images of the Vietnam War.

Rosler draws attention to the home as a site implicated in violence. In response to the potential to ignore atrocities happening far away, she brings harrowing imagery into the most privileged interior, that of the White House, where we see the smiling figure of First Lady Pat Nixon, whose husband, President Richard Nixon, was heavily criticised for his handling of US involvement in the Vietnam War.

The Enchanted Interior exhibition was curated by Madeleine Kennedy. Katherine Pearce is the curator at Guildhall Art Gallery

Please note, Guildhall Art Gallery is currently closed

Stay in touch with The Arts Society! Head over to The Arts Society Connected to join discussions, read blog posts and watch The Arts Society at Home - a series of films by Arts Society Accredited Lecturers, published every fortnight.

About the Author

Katherine Pearce

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition