This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

Curator’s choice: Exceptional botanical art from around the world

Curator’s choice: Exceptional botanical art from around the world

20 Nov 2020

Emma Nicolson shares highlights from a major new exhibition at Climate House in Edinburgh.

Ellie Harrison, Early Warning Signs, 2011. Installed outside Inverleith House, 2020

To celebrate Inverleith House’s transformation into Climate House, we asked Emma Nicolson, head of creative programmes at the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh (RBGE), to share some of the highlights from the institution’s latest exhibition Florilegium: A Gathering of Flowers. This major show comprises work by over 40 contemporary and botanical artists, all of which celebrate the power of flowers.

From common weeds to exotic cultivars, flowers are deeply embedded within our lives and have long been an inspiration to artists. This visually stunning exhibition reveals how flowers can elicit cultural, historic, geographic, social and scientific ideas. Botany, the doctrine of plants, is a basis for the exhibition, drawing together work by botanical illustrators from across the globe alongside contemporary artists who explore our wider relationship to flowers and nature. The exhibition aims to shed light on the living collections of the RBGE and human behaviour through the lens of art.

A florilegium is a book of flowers. It is commonly a group of botanical paintings depicting a particular collection. The collection may represent an exploration of a garden or perhaps a plant family. The RBGE Florilegium project, initiated in 2019, recognises the need to expand the garden’s important collection of botanical illustrations in a planned way to ensure that plants being grown and studied by RBGE staff will feature as new works in the collection. RBGE botanists identify, describe and name new plants and continue to rely on botanical illustration and herbarium specimens as important reference material.

Installation view, photo Tom Nolan

Installation view, photo Tom Nolan

Featuring plants that can be seen growing in the RBGE glasshouses – and others of significant scientific value – the exhibition includes works by artists from Edinburgh to Australia via Italy, Spain, Austria, Taiwan, India, the USA, Russia, Slovenia, Japan, Brazil, Singapore, Qatar, Nepal and Thailand. In addition to established practitioners such as Mieko Ishikawa, Dianne Sutherland and Sansanee Deekrajang, it is a unique opportunity to showcase the works of those less well known.

The artistic depiction of plants has an ancient history and was originally deployed as a means of identification, although, by the end of the Renaissance, botanical painting had also come to be appreciated as an art form in its own right. In Scotland one of the earliest books recording scientific illustrations of plants was in Robert Sibbald's Scotia Illustrata in 1684. Sibbald was the first professor of medicine at the University of Edinburgh and a founder of RBGE. The botanical illustrator’s eye for detail continues to play an important role in RBGE’s 350-year history, bringing together scientific scrutiny and artistic skill to highlight the beauty and diversity of rare and endangered plants and helping to communicate the vital message of conservation.

Thutploy Kaewpradub, Caryota urens

The composition of this watercolour work provides a perfect sense of scale to this solitary fishtail palm tree. This large long-lived tree builds up all its nutrients to produce one flower and fruit before it dies. The artist has depicted the fruits nestled into the tree in two stages with considerable skill and obsessive detail. Once trimmed and dried its leaf can be used as a fishing rod, seen here with all its striations and tears, and there is a clever variation in the greens, helping to lead your eye into the work. The plant’s fruit is easily deconstructed, since its parts are not joined as they would be in nature; lined up here they provide valuable botanical information as well as balancing the page.

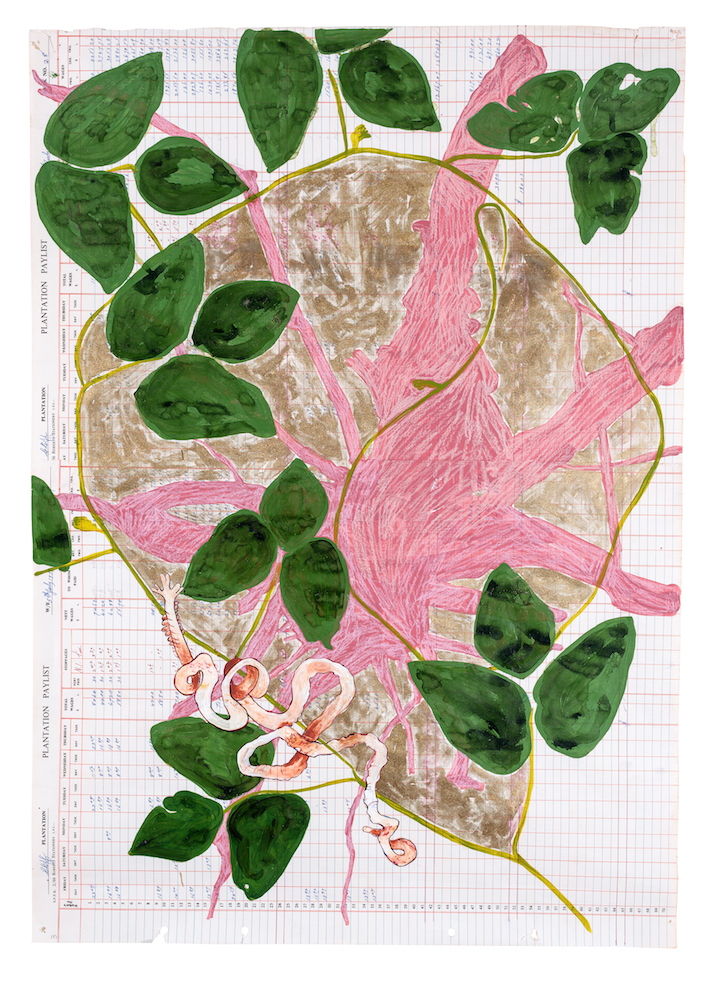

Annalee Davis, one of eight mixed-media drawings, As If The Entanglements Of Our Lives Did Not Matter

Photo Daniel Christaldi

Photo Daniel Christaldi

Annalee Davis is a visual artist living and working in Barbados. Inspired by the concept of phytoremediation – a process whereby plants remove toxins through their root structure – her work unpacks the plantation from the ground up. This drawing on plantation ledger paper bears witness to the colonial and economic complexities of her island home. Layered across accounting sheets, pink roots combine with parasites and wild botanicals to offer healing, including vermifuges – the treatment of wounds and heartache, among other ailments. Davis views wild plants as active agents in the process of decolonising fields, performing quiet revolutions by asserting themselves against an imperial, monocrop landscape. A proliferation of wild plants and trees growing in abandoned sugar cane fields have contributed to greater biodiversity in Barbados since the late 17th century.

Işık Güner, Gunnera tinctoria

Photo: Tom Nolan

Photo: Tom Nolan

This iconic architectural plant has been captured here with the most extraordinary commitment, describing a plant in watercolour with presence and super-fine detail. Its scale (leaves can be up to 2.5 metres across), lush foliage and inflorescence are portrayed in exquisite scientific detail while also capturing an impressive sense of depth, drama and fecundity that this giant of a plant commands. The clever composition echoes the growth of the plant, with its umbrella leaves that form a canopy over the flower stalks and younger shoots. This work is one of 39 illustrations created by the artist for the RBGE on the plants from the woods and forests of Chile.

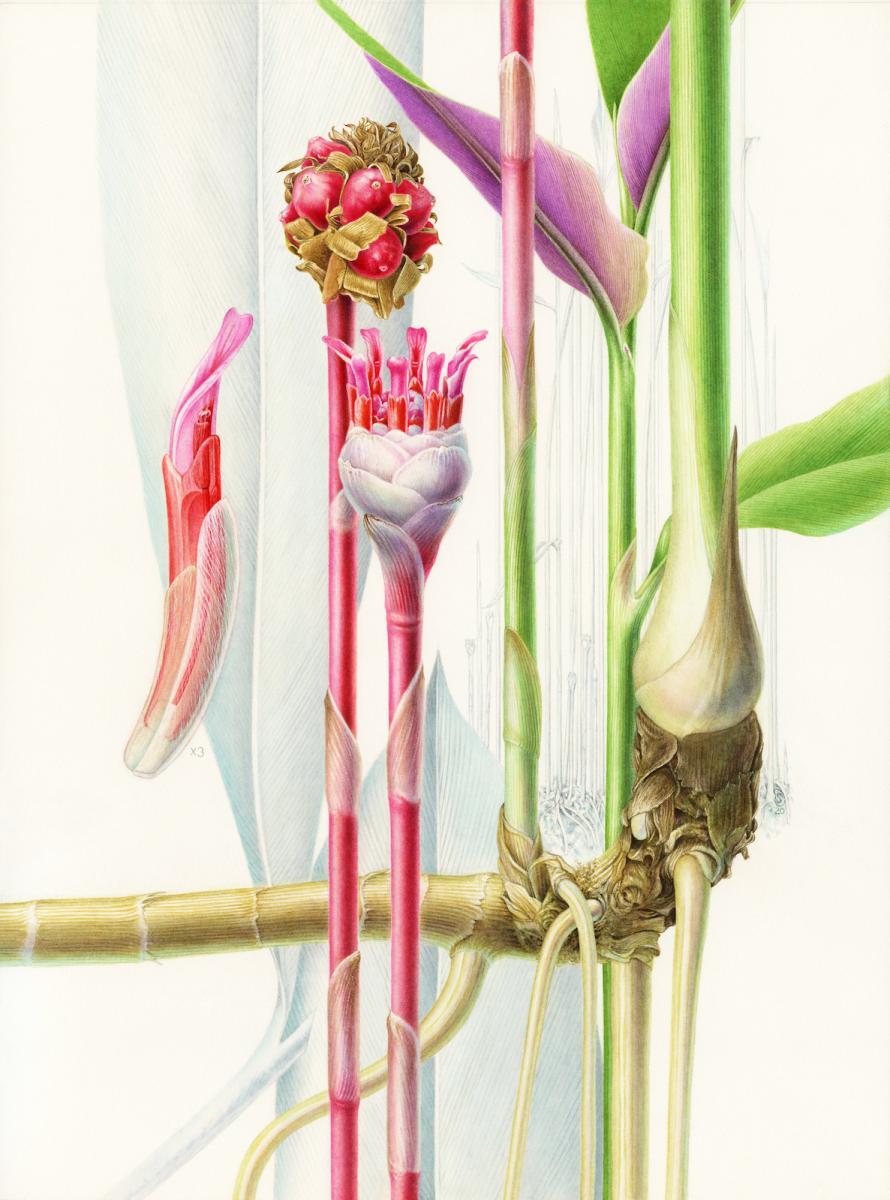

Sandra Doyle, Etlingera maingayi

Also known as the Malay rose, this striking work represents a member of the ginger family – a key area of research for the RBGE. The unusual composition hints at the stature of the plant and highlights the flower, bulb and root. The monochrome leaves in the background give additional detail without the image feeling cluttered and draws attention to the beautifully observed lustrousness of the red flower.

Mariko Ikeda, Pandanus utilis

The screw pine is a palm-like woody evergreen native to the tropics. It is also known as the Christmas palm due to its shape and the fruit that hang like decorations. Painted in July 2020, this beautiful work on vellum has a timeless luminosity to it. The artist has captured the complex three dimensionalities in the prism-shaped fruit by juxtaposing deep tones with striking highlights. The monochrome detail and softness of the flowers stand out against the razor-sharp leaf and scales.

Tapita Yomnage, Xanthoria parietina

Rendered in exhaustive detail, this artwork features a yellowy-orange-coloured leafy lichen, which is one of the most overlooked and common species around. The yellow chemical xanthorin is thought to be produced as a defence against UV radiation to which the plant is exposed in its normal habitat – cement-tiled roofs, exposed twigs and branches etc. The wonderfully convoluted and complex shape of this organism has been recorded to describe the effect of algae turning the plant from green to translucent green-yellow.

Wendy McMurdo, Indeterminate Objects (Flora)

McMurdo’s new series of images was inspired by the flowers growing in the garden beyond her studio. The cycle of germination, growth and renewal that she witnessed from her window seemed in direct opposition to her world inside and online. She has applied software predominantly used to create the virtual shapes in computer games to intervene in her photographs. Taking images of the flowers at various stages in the growing season, she then froze them twice – once in the taking of the shot and then again in reshaping these natural forms through the algorithms of fractal-generating software. The theme of time in relation to the still life – where both growth and decay are often collapsed together into a single picture – is explored. The image of the flower is presented as transient and mutable and symbolic of both life and death.

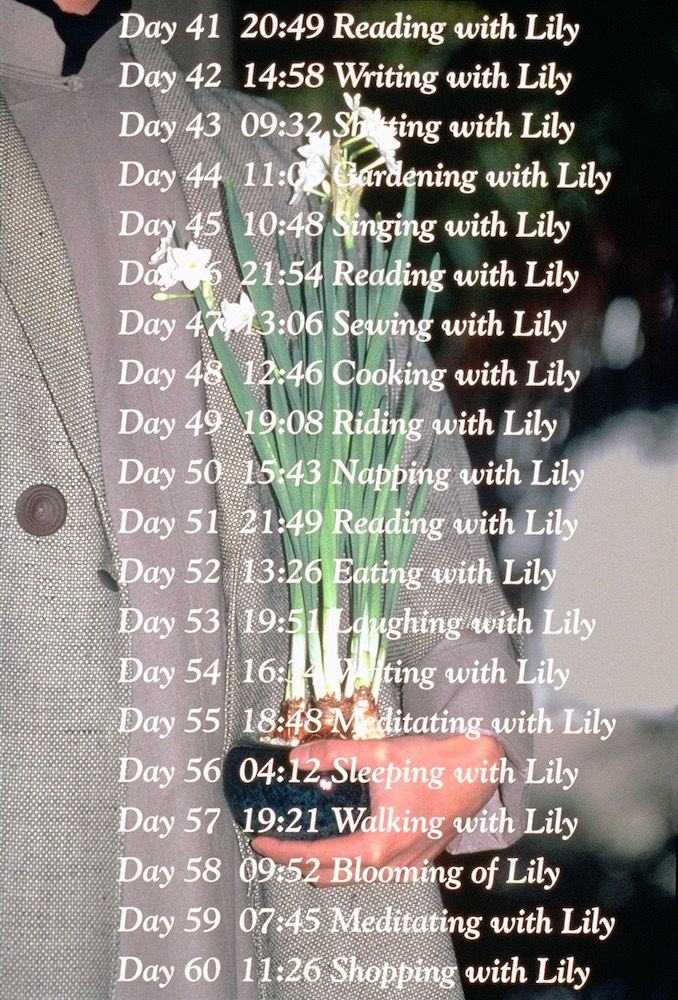

Lee Mingwei, 100 Days with Lily

Courtesy of Lee Studio

Courtesy of Lee Studio

This lyrical litany reminds us of the shortness of time and what connects us to the world. In Lee Mingwei’s works, immaterial gifts such as song, conversation or contemplation are given and received. Many of his projects begin with his personal encounters, which are then transformed into installations. 100 Days with Lily (1995) is a photographic portrait of a project in which Lee cultivated and raised a single lily from seed to death. In response to grieving his grandmother’s death, Lee spent every moment with this flower until it too died.

SEE

Florilegium: A Gathering of Flowers at Climate House, Edinburgh

Until 13 December 2020

About the Author

Emma Nicholson

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition