This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

Cheap cider, drunken brawls and Paul Gauguin

Cheap cider, drunken brawls and Paul Gauguin

3 Sep 2018

It’s 1889, and we’re in a tiny Breton village, at the bottom of a valley guarded by thick forest. The people are dressed in traditional caps, bonnets and aprons. They are deeply superstitious, and practice medieval rituals. The hills roll around us. We are a world away from the thrum and heave of an industrialised Paris.

Paul Gauguin (1848-1903) Bowl of Fruit and Tankard before a Window, c.1890 National Gallery, London. Bequeathed by Simon Sainsbury, 2006

But listen. You’ll hear the sound of a drunken skirmish curdling the milkmaid’s ditty. The forest is filled with rakish men in velvet, working at easels en plein air. One feeds his pet monkey. Their canvases bark with colour, little resembling the landscape before them.

Since the 1850s, the village of Pont-Aven had been an artists’ colony at the forefront of the avant-garde. Fresh from stints at the schools in Paris and Antwerp, painters flocked to the countryside, where the landscape was unspoilt by industrialisation. The living was cheap, the cider was plentiful and nature was at hand. Paris, the art capital of Europe, could be reached by train or coach in a day, and painting materials and artworks could be transported by the same means. The locals became willing and patient sitters; their ‘primitive’ existence and often-bewildering customs a source of great inspiration.

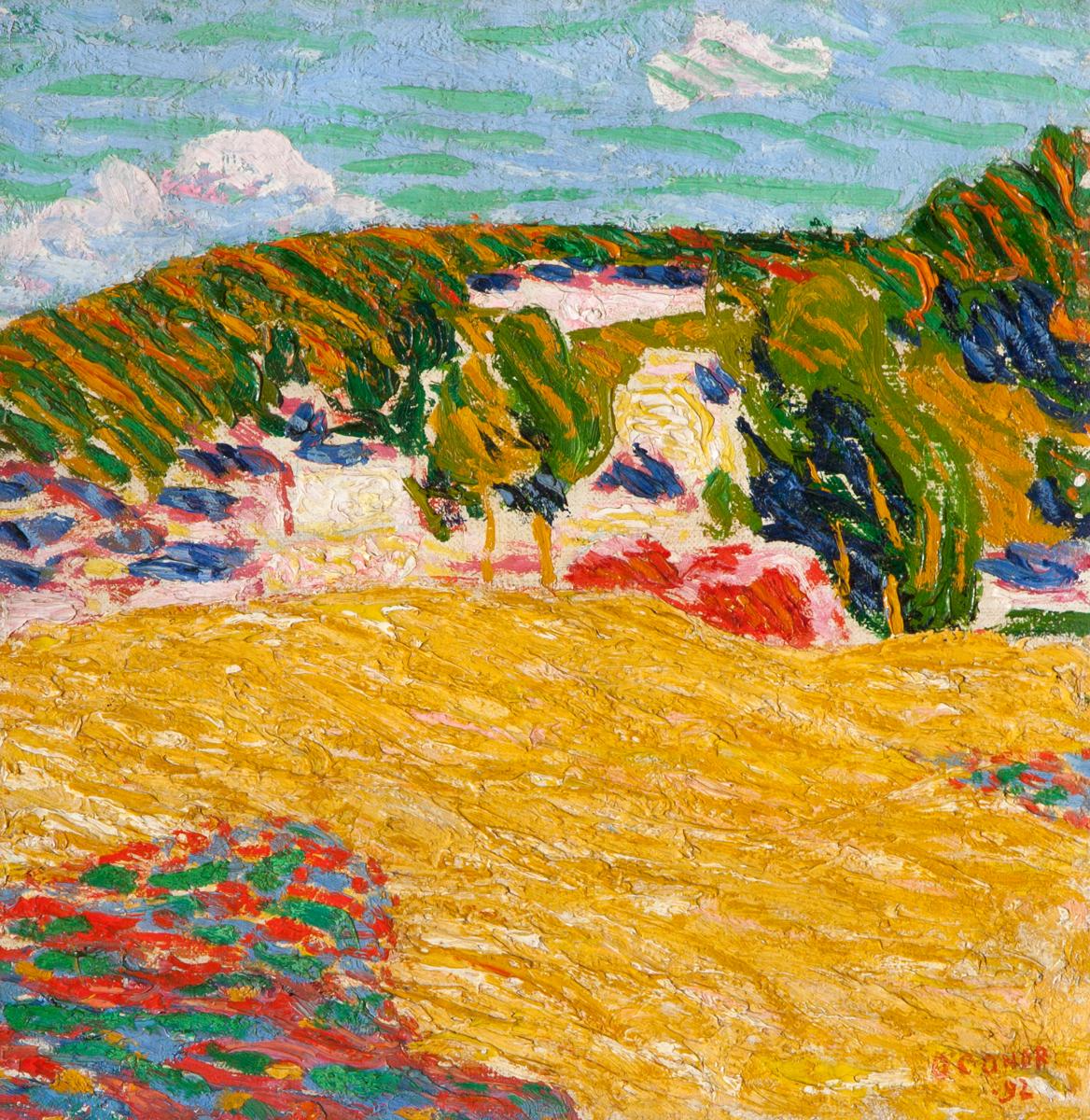

Roderic O’Conor (1860-1940) Field of Corn, Pont-Aven, 1892 © National Museum NI. Collection Ulster Museum

The greatest commodity that this commune had to offer, though, was the exchange of ideas. The local hostelries provided an unparalleled artistic network. They were hotbeds of friendship and rivalry, played out in frank exchanges over long walks in wheat fields. New arrivals could bring news from Paris, and more experienced artists offered lessons. Whole styles would spring up and develop, as artists aped the styles of the most prepossessing among them. In the late 1880s and early 1890s, these included Maurice Denis, Paul Sérusier and Vincent van Gogh, who was a virtual presence by way of frequent exchanges of letters, drawings and paintings with the Pont-Aven residents. The undisputed king of the hills, though, was Paul Gauguin.

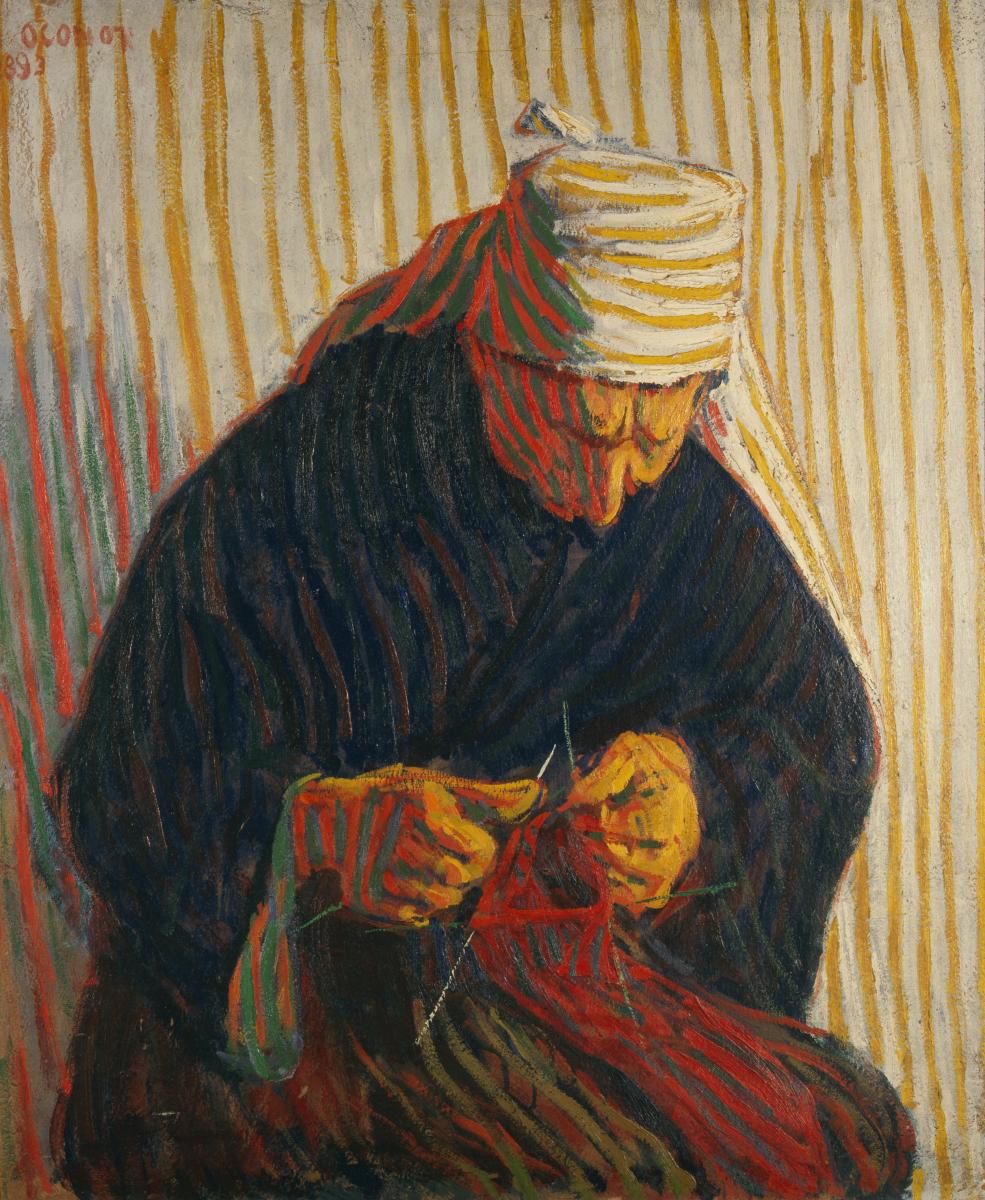

Roderic O'Conor, Breton Peasant Woman Knitting

Gauguin adored Pont-Aven. As he wrote to his friend, Émile Schuffenecker, in 1888: ‘I love Brittany. I find a certain wildness and primitiveness here. When my clogs resound on this granite soil, I hear the dull, matt, powerful tone I seek in my painting.’ Gauguin’s influence on the artists at Pont-Aven cannot be overstated. His clear outlines and bold, counter-intuitive palette of reds and yellows swept through the commune. He taught his fellow residents to abandon the naturalism they had been taught in the academies, telling Sérusier: ‘How do you see these trees? They are yellow. So, put in yellow; this shadow, rather blue, paint it with pure ultramarine; these red leaves? Put in vermilion.’

One of Gauguin’s closest friends and greatest acolytes at Pont-Aven was Roderic O’Conor, the lone Irishman in a sea of French and Belgian artists – and the subject of a new exhibition at the National Gallery of Ireland, Roderic O’Conor and the Moderns: Between Paris and Pont-Aven. The two artists often painted side by side, and, indeed, looking at their paintings side by side where they hang at Roderic O’Conor and the Moderns, you cannot deny the similarities. O’Conor abandons a naturalistic palette and opts instead for shocking reds and pinks, electric blues and orange, applied thickly with a knife.

Roderic O'Conor, Bretonne, c.1903-1904

O’Conor painted in distinctive parallel lines, a feature that he borrowed from the late landscapes of Van Gogh, and you’ll find a great many stripes in the exhibition – both from the Irishman, and from an acolyte of his very own, Cuno Amiet. This show hosts a gaggle of Modernists by whom O’Conor was inspired: Armand Seguin, Émile Bernard, Denis and Sérusier, as well as, of course, Gauguin and Van Gogh.

Nowadays, the village of Pont-Aven has fallen back into its former, desperately picturesque slumber – with the addition of a few more chocolatiers. It is pleasing to think that, for a brief while, it housed and fostered the most radical art the world had ever seen.

Roderic O’Conor and the Moderns is at the National Gallery of Ireland until October 28.

About the Author

The Arts Society

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition