This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

Beyond the Wall

Beyond the Wall

15 May 2017

For a band who put the mind-altering mayhem of psychedelic music on the map, the entrance to Pink Floyd’s first international retrospective seems surprisingly literal. But the Victoria and Albert Museum’s eagerly awaited exhibition celebrating one of the most influential and successful groups of our times defiantly begins in the Bedford van that Syd Barrett, Nick Mason, Roger Waters and Richard Wright took on their very first tour in the 1960s. Those early days of Pink Floyd might sound rather prosaic. But just a decade later they released a multimillion-selling concept album, Animals. On its sleeve is the image of a pig that literally – and iconically – flew over Battersea Power Station. Pink Floyd: Their Mortal Remains attempts to make sense of how Pink Floyd went from a fixture of London’s nascent underground psychedelic scene in 1967 to, with The Dark Side Of The Moon (1973) and The Wall (1979), recording some of the best-selling albums of all time.

The show - and it is a show - is as much an exploration of how their attitude to design and performance was as important and groundbreaking as their music. It is an immersive, sensory and theatrical exploration of the Pink Floyd universe.

Senior curator Victoria Broackes said when the exhibition was announced: “Pink Floyd occupied a distinctive experimental space, consistently pushed artistic boundaries and produced some of the most iconic imagery in popular culture.”

The band’s interest in marrying sound and image wasn’t something they gradually grew into. Come out of the Bedford van, and exhibition visitors will be immediately immersed in the UFO Club, where Pink Floyd regularly played 50 years ago to a backdrop of Peter Wynne-Willson’s experimental light shows. The lighting designer went on to be internationally recognised.

Their 1967 gig at Queen Elizabeth Hall in London – the 50th anniversary of which coincides almost to theday with the opening of this exhibition – was famous for being the first-ever surround sound concert, where a quadrophonic speaker system blasted footsteps, birdsong and laughter across the auditorium. Meanwhile, members of the band chucked potatoes at a gong, set off a bubble machine and watched amused as a crew member dressed as an admiral lobbed daffodils into the crowd.

True, it still sounds ridiculous, but there’s a distinct lineage from this experimental show to what is expected from contemporary bands – for instance, during Coldplay’s arena tour, cannons blasted confetti at an audience wearing individual LED bracelets that pulsed light in time to the music. As Syd Barrett said in 1967: “In the future, bands are going to have to offer more than a pop show. They are going to have to an offer a well presented theatre show.”

Barrett wasn’t unused to hyperbole. But he was right. Curator Broackes noted that “as well as amazing their audience, their performance that day significantly raised expectations of live rock shows. It was a major turning point for the band and a major turning point for rock music in general.” As was the sleeve for Pink Floyd’s second album, 1968’s A Saucerful Of Secrets. In 2017, it almost seems cliched in its psychedelic tropes; the wild colours, the spacey, ethereal shapes. An appreciative magazine review called the cover an attempt to mirror three “altered states of consciousness” – religion, drugs, and Pink Floyd music. But the cliche came from everyone else copying it. Unlike the debut album, The Piper at the Gates of Dawn (1967), there were no headshots of the band – nor even the name of the record. Instead, the first ever album design from their friends Storm Thorgerson and Aubrey Powell had a distinct sense of intrigue.

Thorgerson and Powell’s design company, Hipgnosis, would go on to impart a similarly enigmatic visual identity to Led Zeppelin, Genesis, 10cc, AC/DC, Black Sabbath and Wings. But no sleeve of theirs had quite the impact of that of the prism dispersing light into colour for Pink Floyd’s The Dark Side of the Moon (1973). Mention that record today and it’s likely that the album cover flashes into the mind as readily as the singles Money and Us And Them - and yet there is no text on it whatsoever.

The design spooked record label EMI, but because Thorgerson and Powell were employed by the band, they were free to unleash their creative genius. As band member Dave Gilmour (who replaced Barrett in 1968) put it, Hipgnosis would come up with their own “atmospheric link” to the music.

The record was undeniably fantastic. The Dark Side Of The Moon would never have sold 45 million copies worldwide simply on the basis of a nicely designed sleeve. But the stark cover undeniably lent a sense of mystique to the whole undertaking, which fed into the sense that this was exciting and important music.

When Storm Thorgerson died in 2013, Gilmour said “the artworks that he created for Pink Floyd from 1968 to the present day have been an inseparable part of our work.” It was telling that British rock band Muse, when they wanted a cover to represent a concept album, got in touch with Thorgerson. The results on the sleeve of 2003’s Absolution, unsurprisingly, are excellent.

Excitingly, Aubrey Powell has helped to curate the exhibition, lending not just a sense of authority to the proceedings, but fidelity to the look and feel of Pink Floyd, too. It will be fascinating to see how he celebrates The Wall, Pink Floyd’s 1979 concept album and subsequent tour - not least because the record sleeve was designed by illustrator Gerald Scarfe after Roger Waters had fallen out with Thorgerson. Once again there was no text on the original sleeve: literally just a white brick wall. Scarfe’s handwritten lettering was later added as a sticker or wrap.

When the band toured the record, Scarfe’s animations were projected onto a wall constructed as the show progressed. Meanwhile, huge puppets intended as 3D representations of his characters moved around the auditorium.

It remains one of the most iconic and boldly ambitious moments in pop history – and it was the vision of architect Mark Fisher, whose company Stufish would go on to design most of the grandstanding rock spectaculars of our times, from U2 to Madonna to The Rolling Stones. Interestingly, the whole exhibition space is being designed by Stufish themselves, who promise to bring the same kind of innovation to the V&A as they did to the Pink Floyd albums and live shows.

And yet, for all that Their Mortal Remains is a celebration of the way music dovetailed with image and performance, the question of what an archetypal Pink Floyd design looks like will probably remain unanswered – little connects a blank wall with a cow in a field (the cover to Atom Heart Mother) or a pig above a power station (Animals).

Perhaps their lasting legacy is less about a coherent design ethic and more a wildly ambitious desire to push the envelope, to be unafraid of innovation. It’s a neat coincidence that just a few weeks before the Pink Floyd show opens, a new record is released by Gorillaz – Damon Albarn’s ‘band’ that exists entirely as a series of illustrations, whose albums have concepts and augmented reality apps, and whose performances have included holograms. Pink Floyd, surely, would be proud.

'The Pink Floyd exhibition: Their Mortal Remains' will be on display at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London until 1 October 2017.

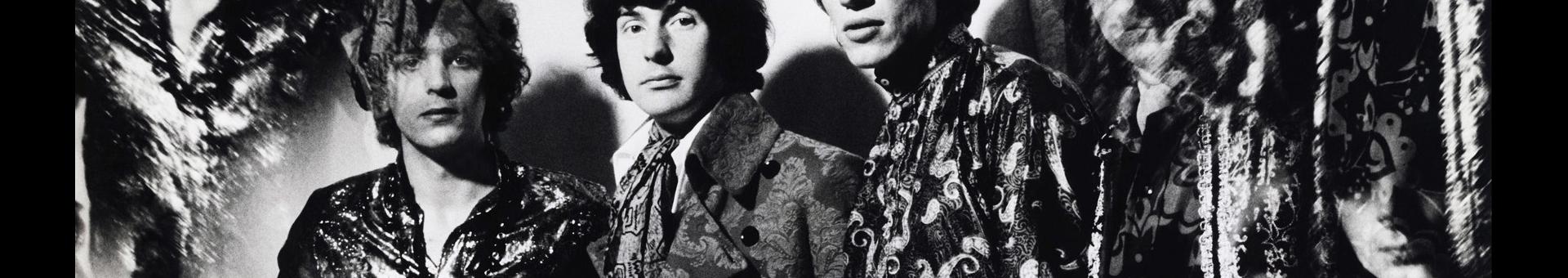

Image: Pink Floyd in 1967, courtesy Victoria and Albert Museum, London

About the Author

Ben East

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition