This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

Become an Instant Expert on William Morris's Beautiful Wallpapers

Become an Instant Expert on William Morris's Beautiful Wallpapers

15 Apr 2021

Artist, poet, conservationist, designer – William Morris was also a master colourist and a one-man pattern-making phenomenon. The wallpapers he created fulfilled his ambition to bring art and beauty into anyone’s home. Arts Society Lecturer Joanna Banham takes up the story

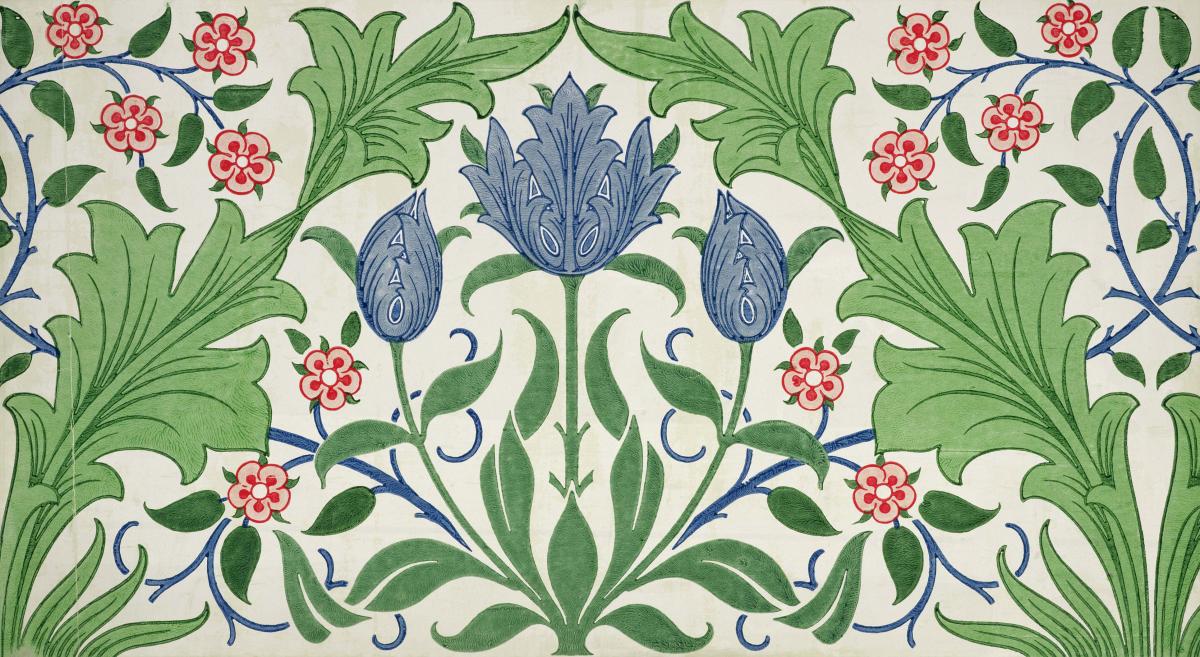

One of William Morris's floral wallpaper designs

One of William Morris's floral wallpaper designs

‘WHATEVER YOU DO THINK FIRSTLY OF YOUR WALLS’

William Morris in 1870, painted by George Frederick Watts

1. THE EARLY DESIGNS

William Morris created over 50 different wallpaper designs, with the first being in 1862, during the intensely creative period when he was decorating his home, Red House, near Bexleyheath, Kent. That project also provided the catalyst for the founding of his company Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co.

The firm initially focused on making expensive, one-off pieces of painted furniture, embroideries and stained glass. But Morris’s move into wallpaper design underlines his early understanding of the importance of making economical, more mass-produced work that could reach a wider audience.

All his wallpapers contained stylised fruit, flowers and foliage motifs. These expressed his love of nature, but his first designs also reflect his interest in medieval sources at the time.

Daisy, for example, featured a simple pattern of naively drawn meadow flowers copied from an illustration in a 15th-century version of Froissart’s Chronicles. Trelliswas inspired by the rose trellises in the Red House garden, as well as the medieval gardens seen in illuminated manuscripts. Even more significantly, both patterns marked a radical departure from the highly naturalistic, brightly coloured floral patterns and the more geometric and stylised Gothic Revival designs that had dominated mid-Victorian wallpaper design to this point.

Daisy, a design from 1864 and featured in Emery Walker's House in London

2. A LABOUR OF LOVE

Given Morris’s general hostility to machine production, it is not surprising that he rejected the use of modern, steam-powered machines to print his designs. Instead, his wallpapers were printed by hand, using traditional techniques that had changed little since their inception in the 17th century.

The design was engraved onto the surface of a rectangular wooden block, leaving the areas that were to print standing out in relief. The block was then inked with pigment and placed face down on the paper for printing. Each colour was printed separately along the whole length of the roll; it was then hung up to dry before the next colour was applied. Pitch pins on the corners of each block helped to ensure that every element of the design registered accurately.

Multicoloured patterns required many different blocks and could take several days to print. The work was time-consuming and labour-intensive, but Morris greatly admired the density of colour and the slight irregularities that resulted from block-printing.

It is these elements that gave his wallpapers a richness and character that could not be achieved by machines.

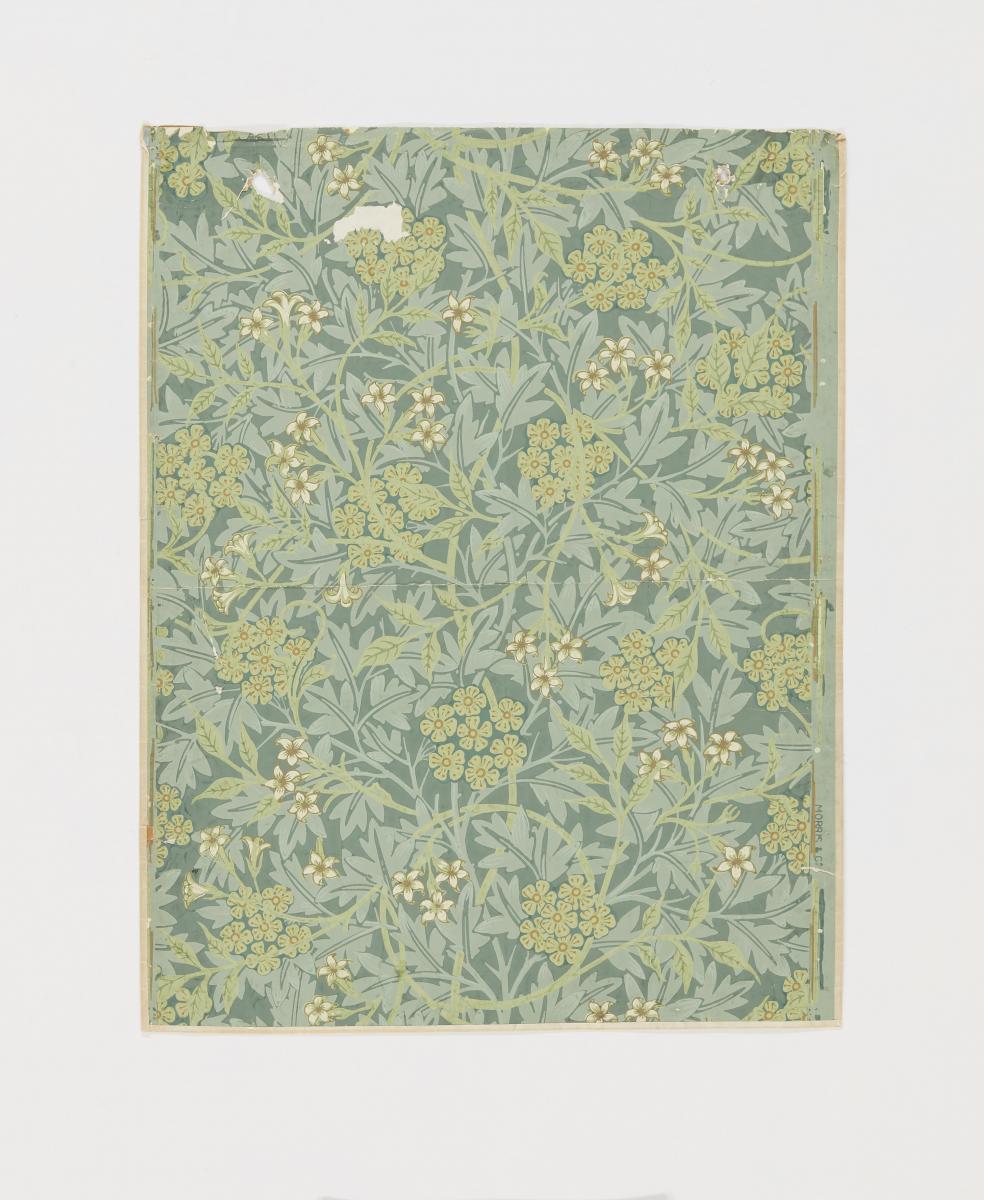

The Jasmine design, created in 1872

The Jasmine design, created in 1872

3. STRUCTURE AND MEANING

By the early 1870s Morris had fully mastered the art of creating complex repeating patterns. As a result, his designs often featured a distinctive structure that involved superimposing one pattern over another.

In his intricate Jasmine, for example, a scrolling tracery of delicately defined jasmine flowers and stems is laid on top of a background formed by an all-over silhouette of hawthorn branches and leaves. The aim of this layering device was to create a sense of variety and depth, and to disguise what he often described as the monotony of endlessly counting the repeats.

Morris always insisted that the test of a successful design was that it provoked thoughts of something beyond itself. ‘I must have unmistakeable suggestions of gardens or fields in my patterns,’ he wrote in his essay on Some hints of Pattern Designing in 1884.

He particularly liked to use the indigenous plants that grew wild in the hedgerows and along the riverbanks of the English countryside. The Willow Bough pattern (1887) was based on drawings that he made of the willow trees growing near his country home, Kelmscott Manor in Oxfordshire – the elegantly intertwining branches and leaves in the design attesting to his abiding love of natural forms.

The Acanthus design of 1875

The Acanthus design of 1875

4. ACANTHUS AND TULIPS

Morris’s patterns of the later 1870s were more stately and several featured the luxuriantly curving leaves of the acanthus plant. Acanthus was the first of a series of large-scale, densely patterned and richly coloured wallpapers. It used two layers of closely interweaving and overlapping leaves to emphasise the vigour of the scrolling acanthus forms. Originally designed for the Speaker’s House in the Palace of Westminster, the pattern required 30 blocks to print and was the most expensive of the company’s wallpapers.

By the 1880s, Morris’s designs had become even more stylised and he increasingly came to accept the mechanical nature of his pattern repeats. Many, like Wild Tulip (1884), also reflected his growing interest in weaving; they used the strong, diagonal, meandering stems that appeared in the 15th-century Italian silks and brocades that he studied at the South Kensington Museum (now the V&A).

Morris had also begun to use stylised devices like small dots, made by the blunted ends of copper pins driven into the surface of the wooden blocks, as a decorative feature within the leaves, stems and flowerhead motifs.

Multiple Morris designs in the home of the designer’s friend, Emery Walker

5. GETTING THE LOOK

Ironically, Morris himself was always somewhat ambivalent about wallpaper.

He described it as a ‘makeshift’ decoration and a cheap substitute for the richer embroidered hangings, tapestries and woven textiles that he preferred to use in his own homes. Nevertheless, his wallpapers proved extremely popular with a fashionable, middle- and upper-class clientele.

Many of his earliest customers were artists and wealthy patrons. His friend, the artist Edward Burne-Jones, requested 55 rolls of Morris papers when he moved into his home, The Grange, in Fulham in 1875; and George, Earl of Carlisle and his wife, Rosalind, ordered large quantities of wallpaper for their country homes, Naworth Castle in Cumbria and Castle Howard in Yorkshire.

From 1877 less exalted customers could buy wallpapers from the company’s new Oxford Street showrooms. There they were displayed alongside other products, including textiles and furnishings, to suggest how a range of Morris items might be combined.

Perhaps the best example of a more ‘ordinary’ Morris interior can be seen in the recently restored Emery Walker's House on Chiswick Mall, London, where the decoration includes the subtle layering of different patterns in wallpapers, curtains and upholstery that was so characteristic of the Morris look.

OANNA’S TOP TIPS

Morris for your home

Morris’s work continues to inspire designers and decorators today. After the demise of Morris & Co in 1940, the blocks for his wallpapers were acquired by Arthur Sanderson & Sons and many are still available in a variety of original and new colours from The Style Library. One of the most recent iterations is architectural and interior designer Ben Pentreath’s updated version of Morris’s Willow wallpaper – vivid proof, if it were needed, of the enduring vitality of Morris’s designs. See here for more.

Places to visit once lockdown lifts

-

Red House in Bexleyheath, Kent, the home Morris conceived when just 24 and designed by his friend, the architect Philip Webb

-

Kelmscott Manor, Oxfordshire, Morris’s country home and his ‘Heaven on Earth’. Currently undergoing conservation, check with the website for future opening

-

Wightwick Manor, near Wolverhampton, a stunning Arts and Crafts house decorated in Morris & Co designs and holding a prime collection of Pre-Raphaelite art

-

The William Morris Society Museum, based in the Coach House and basement of the privately owned Kelmscott House, Hammersmith, once Morris’s London home. Check with their website for details on this and The William Morris Society

-

The William Morris Gallery, Walthamstow, London. Based in Morris’s childhood home, this gallery is devoted to his life and works

-

Emery Walker's House, Hammersmith, London. Walker, an expert typographer, was a friend of Morris’s and his home was close to Kelmscott House. It is filled with Morris & Co designs

Good reads

For the definitive read on the life of William Morris, see William Morris: A Life for Our Time by Fiona MacCarthy, published by Faber.

Images (top to bottom): Floral wallpaper © The Stapleton Collection/Bridgeman Images; George Frederick Watts painting © Stefano Baldini/Bridgeman Images; Daisy © Emery Walker's House; Jasmine and Acanthus © Morris & Co; Emery Walker interior © Emery Walker's House.

IF YOU ENJOYED THIS FEATURE...

Why not forward this on to a friend who you think would enjoy it too?

Stay in touch with The Arts Society! Head over to The Arts Society Connected to join discussions, read blog posts and watch Lectures at Home – a series of films by Arts Society Accredited Lecturers.

About the Author

Joanna Banham

Article Tags

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition