This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

Become an Instant Expert on Leach Pottery

Become an Instant Expert on Leach Pottery

23 Jun 2020

This year the Leach Pottery is marking its centenary. Considered by many to be the birthplace of British studio pottery, it was founded in 1920 by Bernard Leach with help from his friend, the Japanese potter Shoji Hamada. Our expert tells us the story of the pottery and its creator.

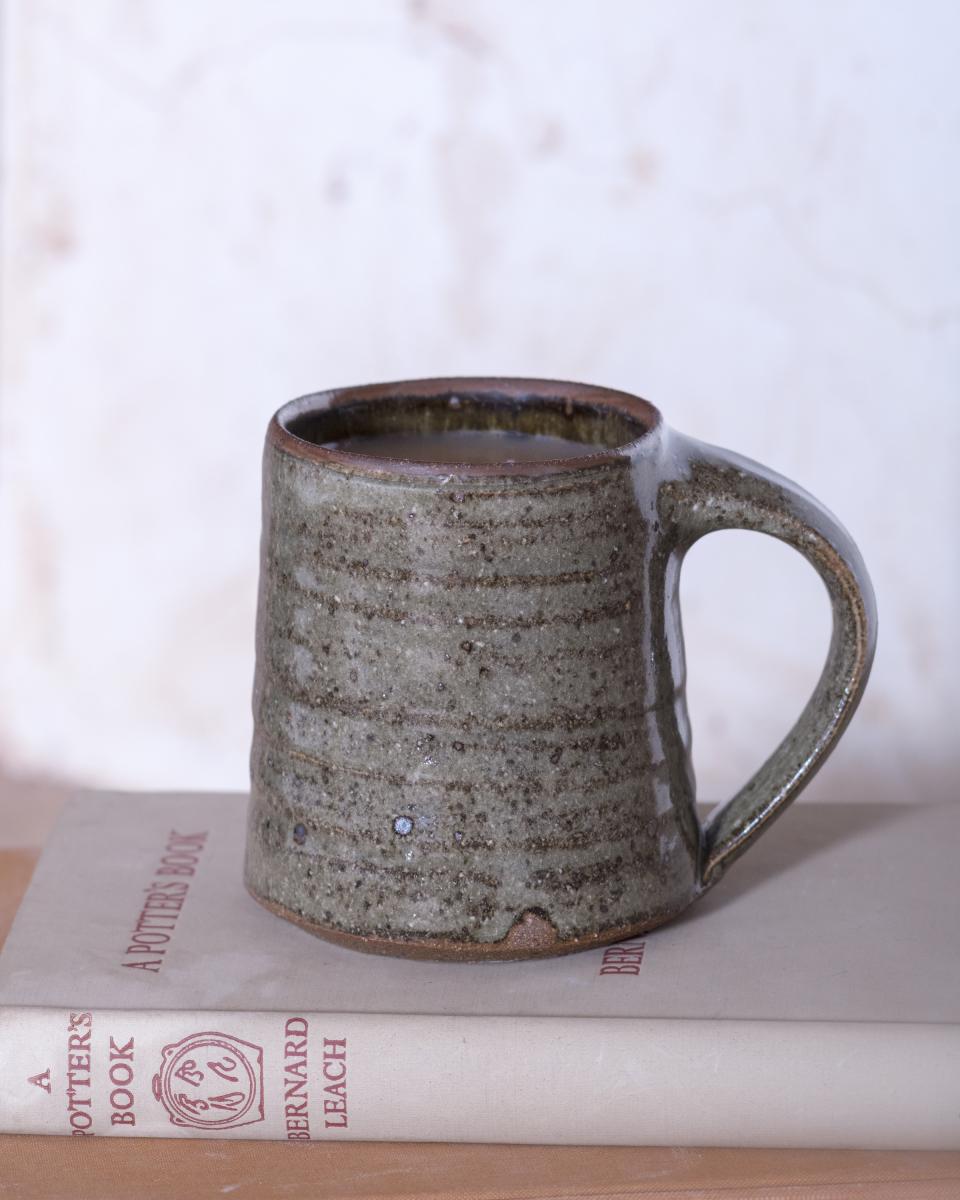

Large Leach Standard Ware Mug in Ash Glaze © Matthew Tyas

Large Leach Standard Ware Mug in Ash Glaze © Matthew Tyas

1. LESSONS FROM JAPAN

Potter and writer Bernard Leach (1887–1979) remains one of the most important figures in the history of British ceramics. Widely considered the father of British studio pottery, Leach is credited with revitalising the tradition of handmade pottery in England, in contrast to ceramics made industrially in factories.

Born in Hong Kong to British parents, Leach spent part of his early childhood in Japan. He later studied at the Slade School of Art and School of Art in Kensington, London, where he was taught etching by artist Frank Brangwyn.

In 1909, Leach returned to Japan to pursue life as an artist, initially as an etcher, but an experience at a ‘raku' party, at which guests decorated pots and watched as they were rapidly fired in a portable kiln, was to transform his life.

Spurred by what he’d seen, Leach took lessons in pottery, learning the art of throwing, glazing and traditional Japanese calligraphic decoration. After nine years in Japan and achieving moderate success with his pottery there, he was ready to return to England.

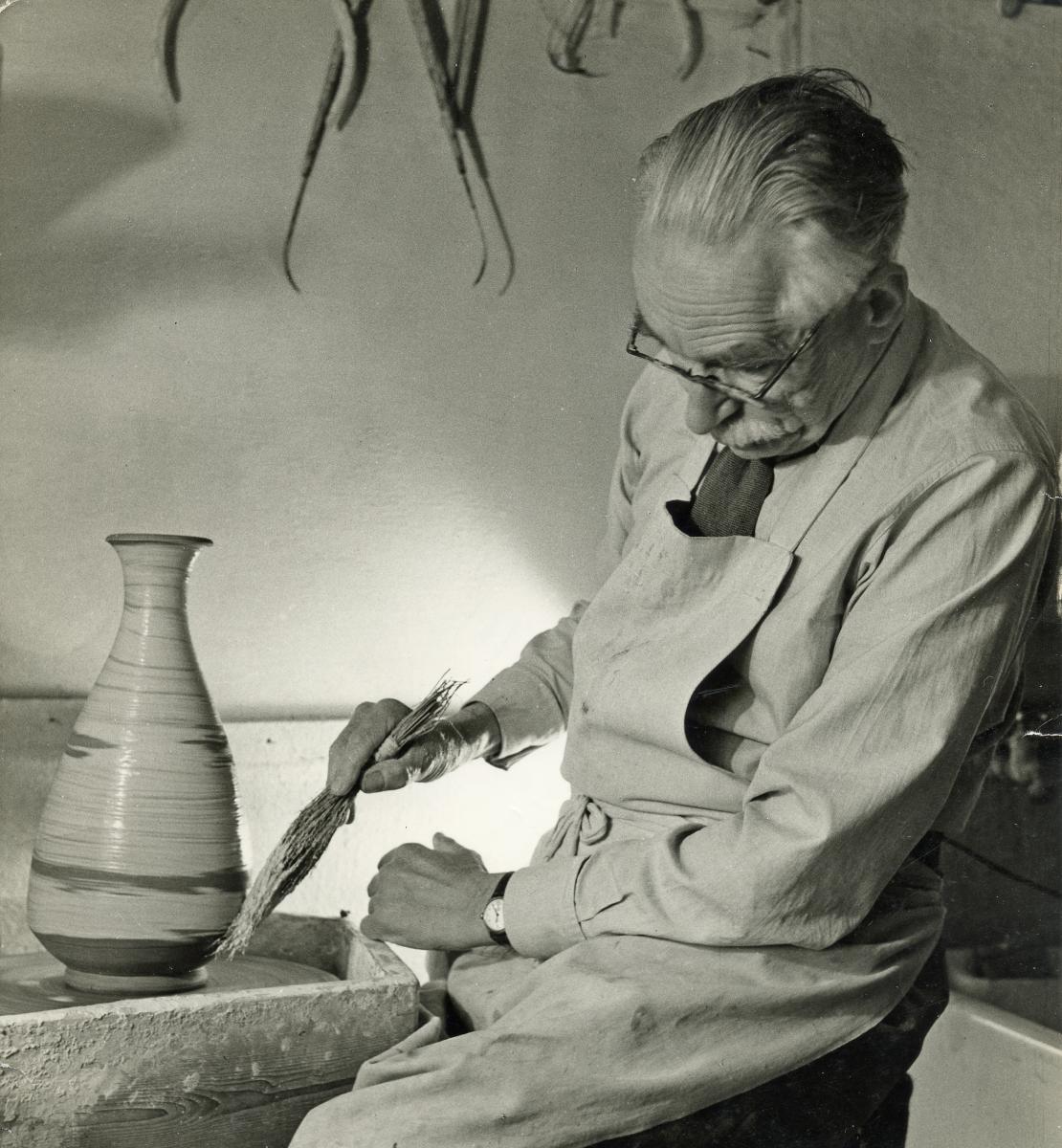

Portrait of Bernard Leach, The Crafts Study Centre, University for the Creative Arts © The British Travel and Holiday Association

2. A NEW ENDEAVOUR: THE LEACH POTTERY

In 1919, Leach received an offer of a loan that would enable him to set up a small studio pottery in St Ives, Cornwall, to complement a new Guild of Handicrafts there.

In 1920, he returned to England with his good friend, skilled Japanese potter Shoji Hamada (1894–1978) who, over the next three years, helped him build the pottery in this unlikely location, away from rich supplies of clay or wood to fuel the kiln. After teething problems, the pair began to produce porcelain, slip-decorated earthenware (reviving the tradition of 17th-century British slipware) and ash-glazed stoneware, inspired by the Japanese and Chinese ceramics that Leach had encountered and collected abroad.

By the 1920s, Japanese and Chinese pottery was viewed as the pinnacle of ceramic achievement, especially stoneware made during the Chinese Song dynasty (960–1279), which had become popular with European collectors. It was seen as a gold standard by which modern ceramics could be compared.

Leach copied glazes and forms, but not slavishly. Although initially gallerists and critics were more interested in the work of some of Leach’s more cosmopolitan counterparts, his free and expressionistic brushwork decoration was always a source of praise.

Fireplace pre-restoration © Matthew Tyas

3. LEACH'S IDEAL OF THE ARTIST-POTTER

Based loosely on Arts and Crafts ideals, Leach argued for the importance of ‘artist-craftsmen' who were ‘the chief means of defence against the materialism of industry and insensibility to beauty’.

In opposition to industrial pottery, he viewed the creation of ceramics as a craft ideally suited to a rural environment, resulting in beautiful handmade objects for everyday use. Leach was committed to the studio model of working, employing a series of pupils and apprentices who went on to become successful potters, including Michael Cardew and Katharine Pleydell-Bouverie.

During the 1930s the pottery nevertheless struggled to make a profit. Leach left it mostly in the hands of others while he travelled, taught and spent a short time establishing a pottery at Dartington.

He also turned his attention to writing and published his first full-length work, A Potter’s Book, in 1940. Drawing on his experience in East Asia and combining technical explanation with praise of making pottery as a romantic, anti-industrial, self-sufficient and spiritually fulfilling way of life, this book proved to be a tonic for a post-war nation. It became a bestseller and was hailed as the ‘potter’s bible’.

From here on in, Leach’s career and reputation soared.

A fluted bottle by current Leach apprentice, Annabelle Smith © Roelof Uys

A fluted bottle by current Leach apprentice, Annabelle Smith © Roelof Uys

4. SUCCESS AND STANDARD WARE

Leach continued to make a small number of unique and more expensive ‘exhibition' pots in between international lecture and demonstration tours. However, the security and future of the Leach Pottery was secured by the success of the ‘Standard Ware' range, designed by Leach and his son, David (1911–2005).

Although Leach had often spoken out against mass production, it became clear that the pottery would only survive if it was able to adopt larger-scale and repetitive production. This resulted in a range of strong and robust stoneware for the table, which could be made quickly by hand by other potters employed at the pottery.

By 1950, the range included 60 different items and the pottery produced over 20,000 pieces per year in three different glazes. Although Leach played little part in producing Standard Ware, this range spread his style far and wide as it was adopted and adapted by potters around the world.

Leach’s final years – a whirl of travel, honours, TV appearances and retrospective exhibitions – cemented his reputation. He continued to make pots for exhibition until 1972, while his third wife, Janet, took over the day-to-day running of the Leach Pottery.

Old throwing room © Matthew Tyas

5. LEACH'S LEGACY AND THE POTTERY TODAY

Leach was a complex and paradoxical figure; he praised the humility of the 'unknown craftsman' but was personally ambitious and hyper-aware of his own brand.

He presented himself as an interpreter of 'Eastern' ideas about folk art, but had come into contact with only a handful of elite English-speaking Japanese artists.

His writings emphasised the importance of personal, creative freedom in making pots, but the organisation of the Leach Pottery left apprentices with little room for imagination.

Leach believed everyone should have access to handmade objects, but the pots he made himself were expensive and aimed at collectors. However, his consistent advocacy for ceramics as an important, vital and rewarding craft and way of life transformed studio pottery.

Leach’s pupils taught hundreds of others in turn, many finding their own voice and aesthetic but owing this transference of skill to the ‘Leach tradition’.

The Leach Pottery continues to welcome apprentices and make works that are, in Leach’s words, ‘inseparably practical and beautiful’. The pottery now includes a gallery and museum and enables visitors from around the world to experience the joy of clay, while promoting new thinking and approaches to ceramics alongside those established by Bernard Leach 100 years ago.

A Bernard Leach bottle with leaping fish design, image kindly supplied by The Crafts Study Centre, University for the Creative Arts

A Bernard Leach bottle with leaping fish design, image kindly supplied by The Crafts Study Centre, University for the Creative Arts

HELEN'S TOP TIPS

Hone your collector's eye

Ceramics made by Bernard Leach and Shoji Hamada are collectable. All ceramics made at the Leach Pottery are stamped with the Leach Pottery seal, but the pieces made by Bernard Leach himself also have his own personal seal. These are rare – and expensive.

Visit the Leach Pottery

Renovated and restored, the pottery reopened to visitors in 2008. Ordinarily, it is open to visit, and the shop, selling modern Standard Ware (although not to the original designs) and works by current potters, operates in person and online. Please check for current opening details.

Discover Leach works

As well as the Leach Pottery, many museums have pots by Leach and his pupils in their collections. These include York Art Gallery, The Fitzwilliam Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum. Leach’s own collection of 'source' pots is in the Crafts Study Centre (Farnham).

Find time for some reading

If you’d like to find out more about Leach, a good place to start is the excellent biography written by the late potter, writer and activist Emmanuel Cooper. To mark the centenary of the Leach Pottery, Yale University Press has re-released this biography – Bernard Leach: Life and Work in paperback.

For a more critical take on Leach’s legacy, see Edmund de Waal’s Bernard Leach.

Alternatively, you can read Leach’s own words – A Potter’s Book has never been out of print and remains available today.

OUR EXPERT'S STORY

Helen Ritchie is a lecturer, writer and curator responsible for researching and interpreting the modern Applied Arts collection at The Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge.

Her particular interests include British studio pottery, contemporary crafts and artist/designer jewellery and metalwork. Recent exhibitions include Things of Beauty Growing: British Studio Pottery, in partnership with Yale Center for British Art, and Flux: Parian Unpacked at The Fitzwilliam Museum, in partnership with artist Matt Smith.

She is the author of Designers and Jewellery 1850–1940: Jewellery and Metalwork from The Fitzwilliam Museum. Among her lectures for The Arts Society are British Studio Pottery: A Concise History and A Design Evolution: Jewellery and Metalwork 1850–1940.

Stay in touch with The Arts Society! Head over to The Arts Society Connected to join discussions, read blog posts and watch Lectures at Home – a series of films by Arts Society Accredited Lecturers, published every fortnight.

About the Author

Helen Ritchie

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition