This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

Become an Instant Expert on The Boy Genius Thomas Lawrence

Become an Instant Expert on The Boy Genius Thomas Lawrence

13 Oct 2020

Born in 1769, by the age of 10, Thomas Lawrence was already showing remarkable artistic ability. Our expert, Amina Wright, explores the story of the boy that went on to become president of the Royal Academy of Arts.

Self-portrait of Thomas Lawrence aged 18

Self-portrait of Thomas Lawrence aged 18

‘MY DEAR MOTHER, I AM NOW PAINTING A HEAD OF MYSELF IN OILS, AND I THINK IT WILL BE A PLEASURE TO MY MOTHER TO HEAR IT IS MUCH APPROVED OF. YOUR EVER AFFECTIONATE & DUTIFUL SON, T. LAWRENCE’

Head of Minerva Drawn at Oxford by Master Lawrence at the Age of 11 Years (1779)

Head of Minerva Drawn at Oxford by Master Lawrence at the Age of 11 Years (1779)

1. PORTRAIT OF THE ARTIST AS A YOUNG PRODIGY

The portrait painter Thomas Lawrence first came to public attention as a boy in the 1770s, when his father kept a superior coaching inn, the Black Bear at Devizes, Wiltshire. Travelling from London to the fashionable spa town of Bath, the novelist, diarist and playwright Fanny Burney was one of many famous guests at the Bear; stopping there in 1780 she found the innkeeper’s family to be well read and musically gifted. Their youngest son, Thomas, was ‘a most lovely boy of 10 years of age, who seems to be not merely the wonder of their family, but of the times for his astonishing skill in drawing'.

The actor David Garrick, a regular at the Bear, was equally impressed by Tommy’s acting skills and he foresaw his future success ‘poised between the pencil and the stage’. The child regularly attended performances at the Theatre Royal in Bath with his father, an aspiring thespian and poet who would return actors’ hospitality in the green room with a welcome at the Bear. This ensured that Lawrence’s reputation as a rising star spread through the literary and artistic networks of Bath and Wiltshire.

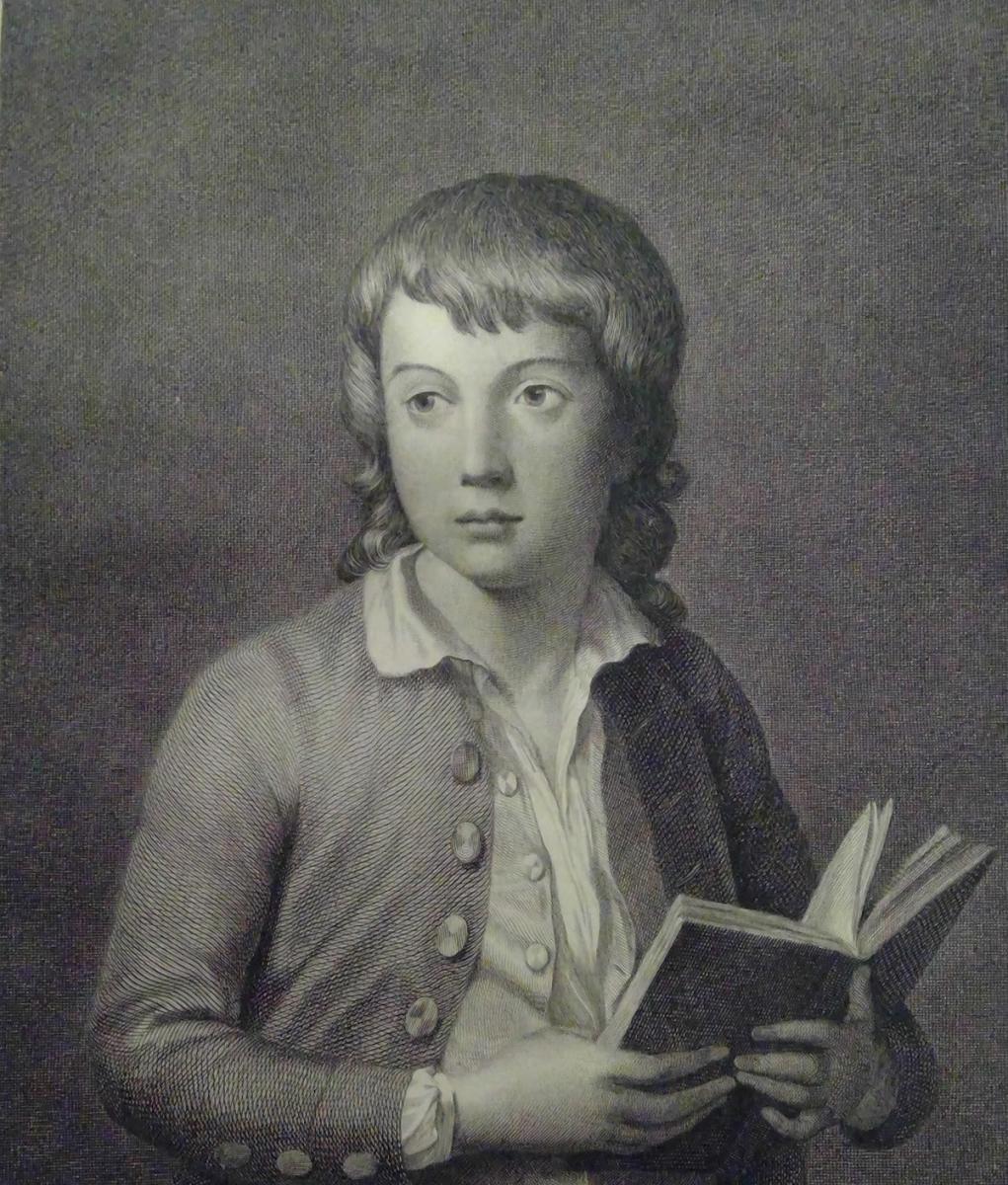

Master Lawrence, an engraving by JK Sherwin, in 1781, probably after William Hoare

Master Lawrence, an engraving by JK Sherwin, in 1781, probably after William Hoare

2. STRIKING LIKENESSES

Days after Thomas’s 11th birthday, his father announced the failure of his inn-keeping business. Suddenly homeless, the family had to find a new source of income. Lawrence and his father had spent the previous autumn in Oxford, where they found generous patrons among the fellows of the university.

This fancy head of Minerva is typical of the little drawings Lawrence was selling at this time. Although the classically inspired composition has the appearance of an antique intaglio, it is actually an unidealised profile dressed up in a theatrical costume, with careful attention given to the reflective surfaces of the chased armour and helmet. Lawrence seems to be taking delight in discovering the variations of texture that a graphite pencil can produce. It would be at least a year before the young artist would find the confidence to abandon profile and allow his sitters to relax into more natural poses.

The trip to Oxford was evidently successful enough for Lawrence’s father to realise his son’s potential as a gold mine. By November 1780 the family had settled in Bath, where he regularly advertised his young son’s services to ‘the Nobility and Gentry’ as a swift, reliable and charming maker of ‘Striking Sketches of their Likenesses’.

Unfinished Portrait of a Young Girl, c.1790

Unfinished Portrait of a Young Girl, c.1790

3. PERSONS OF THE FIRST DISTINCTION

Lawrence spent the next six years in Bath perfecting his drawing in pencil and mastering the art of pastel painting, then a very popular medium for portraits. It offered all the colour and texture of oil paint, but none of the inconvenient drying time.

Through a combination of clever publicity (much of it by word of mouth), celebrity endorsement from the actors and literati of his father’s circle, and a convenient location opposite the New Assembly Rooms, Lawrence was able to find as much work as his parents needed to keep the family comfortable. But perhaps the most important element in his success was not so much his father’s ambition, as his own mature and charismatic personality. Anecdotes speak of the lad as a welcome guest in some of Bath’s most elegant drawing rooms, copying Old Masters in the city’s finest private collections and charming the Duchess of Devonshire.

His greatest champions were the female artists and writers of the Bluestocking Circle (several of whom were neighbours of the Lawrence household) and the actress Sarah Siddons. Lawrence’s portrait of Siddons as the tragic heroine Zara secured his reputation in London, just as she was taking Drury Lane by storm.

Elizabeth Farren, Later Countess of Derby, 1790

Elizabeth Farren, Later Countess of Derby, 1790

4. REFINING HIS TECHNIQUE

When Lawrence was 17 he settled in ‘a suite of handsome apartments over a pastrycook’s shop’ in London’s Leicester Square, close to the house of Sir Joshua Reynolds, the founding president of the Royal Academy.

Sir Joshua was one of many influential mentors and patrons who encouraged the young artist to develop his oil painting technique. As a painter, Lawrence quickly reached a remarkable level of competence. His method of working in oil was an unusual and painstaking one, firmly rooted in his confidence as a draughtsman.

He would spend the first day sketching in chalk directly onto a light-coloured ground, only to paint over his underdrawing with lines of liquid paint. Then he would gradually build up areas of colour, beginning with the face. He contrived his paintings so that they appeared to have been dashed off with ease and panache, giving the finished portrait an exceptional immediacy and spontaneity.

Although Lawrence has, not unreasonably, been accused of flattering his subjects with slender poses and sumptuous textiles, and of using intense colour and highlighting to make eyes brighter and lips fuller, his real passion was for ‘expressing with truth the human heart in the traits of the countenance'.

5. COMING OF AGE

It was this combination of qualities that made the artist such a sensation at the Royal Academy exhibitions of the late 1780s and early 1790s. In 1790, on the eve of Lawrence’s 21st birthday, his father wrote to an old Wiltshire patron bursting with pride and gratitude at ‘the great name my son has so wonderfully acquired’.

The Royal Academy’s annual exhibition had just opened with no fewer than 12 works by Lawrence, the most notable being a sensitive full-length portrait of Queen Charlotte (now in the National Gallery), at a time when she was still recovering from the shock of her husband George III’s sudden ‘madness’ and gradual return to health. Lawrence had painted it during a three-month residence at Windsor Castle. The Queen’s portrait had a rival in another outstanding full-length, as bright and energetic as Her Majesty’s was wistful, of the comic actress Elizabeth Farren.

Lawrence went on to be elected president of the Royal Academy in 1820 and to be one of the most influential men of his time. When he died, exhausted at the age of 60, he was honoured with burial in St Paul’s Cathedral. Yet it’s interesting to note that, in April 2019, the 250th anniversary of his birth passed silently without national celebration. Such is the fickleness of fashion.

AMINA'S TOP TIPS

Books to read

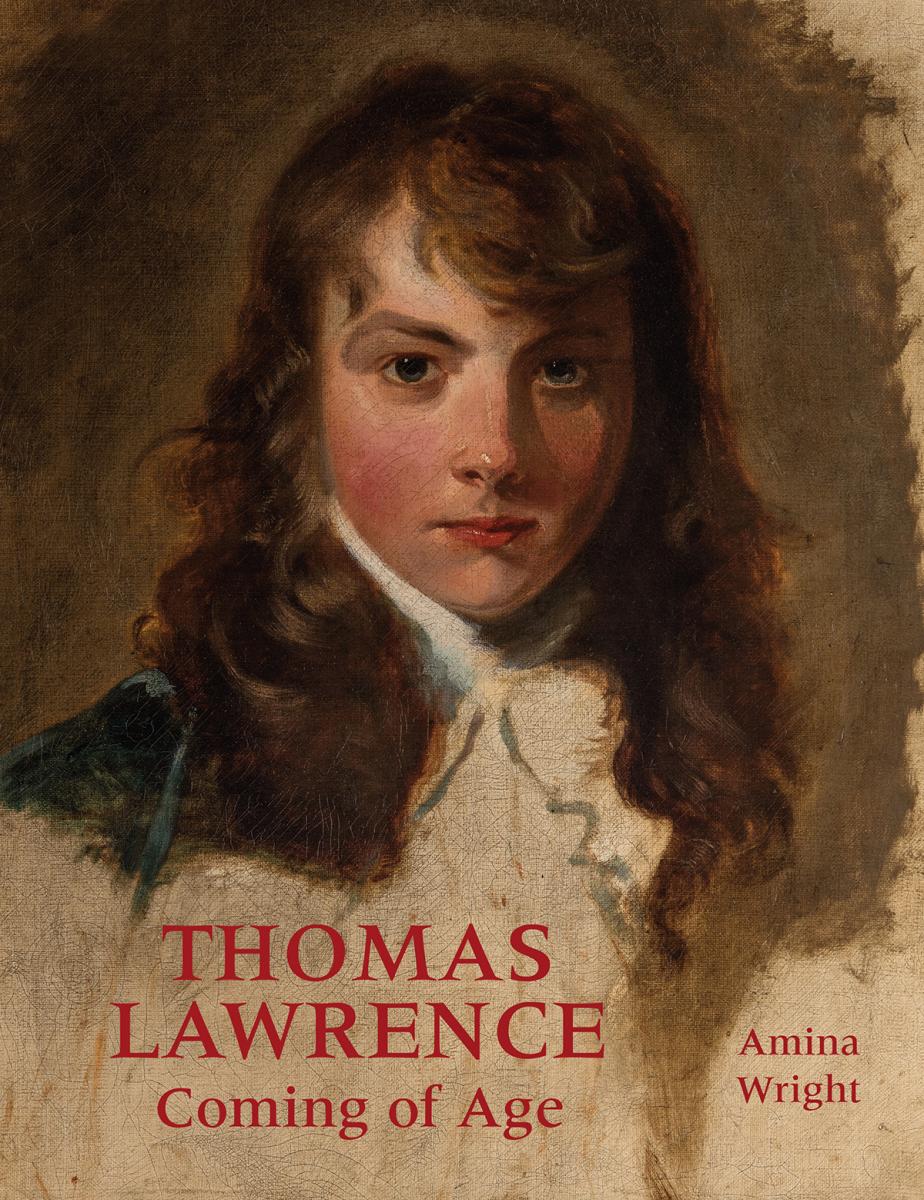

• Michael Levey’s Sir Thomas Lawrence (Yale University Press, 2005) is the definitive survey of the artist’s life and work

• My book, Thomas Lawrence: Coming of Age (Philip Wilson, 2020), celebrates the West Country boy’s early years until the age of 25, and his experience of growing up an artist

Where to see works

Some of Lawrence’s earliest drawings, pastels and paintings will be returning to Bath early next year in the exhibition Thomas Lawrence 1780-1794: Coming of Age at the Holburne Museum (9 January to 3 May 2021).

If you can’t wait until then, the best place to see Lawrence’s later work this autumn is at Windsor Castle’s extraordinary Waterloo Chamber, packed from floor to ceiling with 20 of his late masterpieces.

Lawrence was so prolific and his portraits so popular well into the 20th century that you won’t have to travel far to find them reproduced in engravings and photographic prints, or on old biscuit tins, china and chocolate boxes. Try browsing online or in charity shops for some Lawrence-inspired kitsch.

OUR EXPERT'S STORY

Amina Wright is a curator of historic art collections, exhibitions and interiors, formerly for English Heritage and the Holburne Museum in Bath, and now as senior curator of the Faith Museum at The Auckland Project, County Durham. She has published and lectured for The Arts Society on the artists of Georgian Bath, including Thomas Gainsborough, Joseph Wright of Derby and Sir Thomas Lawrence. Amina recently completed an MA in Christianity and the Arts at King's College London, with a study of images of St Joseph, the basis of her popular lecture Joseph of Nazareth: Best Supporting Actor.

IF YOU ENJOYED THIS INSTANT EXPERT STORY...

Why not forward this on to a friend who you think would enjoy it too?

Stay in touch with The Arts Society! Head over to The Arts Society Connected to join discussions, read blog posts and watch Lectures at Home – a series of films by Arts Society Accredited Lecturers.

About the Author

Amina Wright

Article Tags

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition