This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

The beat of time

The beat of time

6 Oct 2017

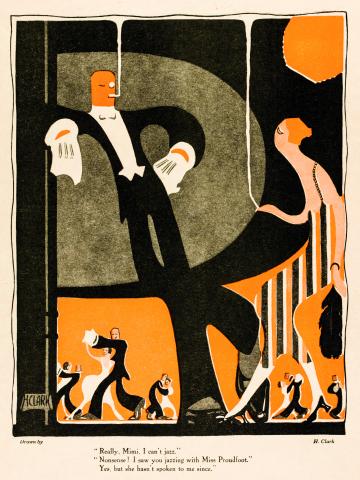

Jazz has become ingrained into our cultural landscape over the past century. Ahead of a new exhibition sponsored by The Arts Society, Alyn Shipton explores how JAZZ changed the way we danced, listened and lived.

Last April, at the free stage tent of the Cheltenham Jazz Festival, a crowd of young families was stretched out on the grass, enthusiastically clapping along with a set by Kansas Smitty’s House Band. The idea that music from the Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington generation of musicians would be eagerly embraced by listeners of all ages almost 100 years after the sounds of jazz first began to be heard on this side of the Atlantic might have struck those pioneers as extraordinary. And they would have been equally surprised by the singer Mica Paris, mainly known for her soul singing, a few hundred metres away in the main jazz tent, paying homage to Ella Fitzgerald with a young multicultural band drawn from many segments of today’s British society, working alongside one another in a way that would have been unthinkable at the dawn of the 1920s.

Jazz has become engrained in the country’s cultural landscape, and although it has perhaps only been truly popular — in the sense of being the dominant form of popular music — two or three times in that century, its place is secure. Its moments of popularity, looking back from the present, came most recently in the ‘trad’ jazz boom of the 1950s and 1960s, before that in the big band swing of the WW2 era, and — most significantly for the forthcoming exhibition at Two Temple Place, presented by The Arts Society and Bulldog Trust — during the ‘jazz age’ of the 1920s and 1930s.

Back then, flapper dresses, bobbed haircuts, double-breasted pinstripe suits and fedoras might have been the outward trappings of jazz couture, but what the curator of this event, Prof Catherine Tackley (Head of Music at the University of Liverpool) is aiming to do is more profound. She wants us to get under the skin of Britain’s inter-war period and explore the jazz age in terms of what we heard, who was playing it, how and where we danced, where we drank, what we drank from (coffee sets, jugs, and other tableware), what we read, what we wore and what we saw, in terms of the visual depiction of jazz.

Jazz was fortunate in that it arrived just as the predominant means of distributing music to a mass audience was changing profoundly. In the 21-year span of the exhibition, music went from its traditional 18th- and 19th-century mode of communication to modern mass media in one giant leap. During and just after WW1, sheet music was the main channel by which new songs and tunes reached the public. Irving Berlin and other successful songwriters of the 1910s had become used to printed music sales in the hundreds of thousands, and most homes in all social classes had access to a piano, even if they did not own one directly.

So the exhibition will rightly focus on the final hurrah of the mass sales of printed music, with elaborately illustrated covers, chord symbols for banjo and ukulele players and beautiful music engraving that was the acme of the typesetter’s art. And it will show how pianolas, those automatic pianos that reproduced performances by means of punched paper rolls and compressed air first brought virtuoso playing to the drawing room. The average British drawing room was considerably less opulent than the surroundings of Two Temple Place where the exhibition will be held, but it is nonetheless significant to experience the music of this era in the environment of William Waldorf Astor’s mansion.

Close by the sheet music and pianola in the exhibition will be the agents of change, the gramophone and the wireless. With the advent of the 78rpm record, a whole band or the voice of a virtuoso singer could be brought to the drawing room. Within a decade of 1918, sheet music sales had collapsed on both sides of the Atlantic, and record sales began to boom, with the African ![]() American singer Bessie Smith and the avuncular white bandleader Paul Whiteman both being among those first to reach the million-selling mark worldwide. And with the BBC’s radio relays from the Savoy in London, it also became possible to listen at home to some of this country’s finest jazz musicians at the very moment they were playing.

American singer Bessie Smith and the avuncular white bandleader Paul Whiteman both being among those first to reach the million-selling mark worldwide. And with the BBC’s radio relays from the Savoy in London, it also became possible to listen at home to some of this country’s finest jazz musicians at the very moment they were playing.

Of course there was controversy at the BBC about what should be broadcast, when it should be heard, and which elements of public taste should be catered for, but then as now, if the arguments seemed equally weighted on both sides, the BBC — aiming at Reithian impartiality — reckoned it had got things about right.

So if this shows us something of the changes in how jazz reached its public up to 1939, what can we learn of the musicians and instruments that actually made the music? The exhibition will offer us the chance to get close and personal with the artefacts on which jazz was performed. British brass and woodwind manufacturers swiftly caught on to making ideal instruments for jazz performance, rivaling their French and American counterparts, just as British drum makers constructed kits — or trap sets as they were known then — that laid the foundation for such long-lived and popular brands as Premier drums, whose Leicester factory opened in 1922. And as well as the instruments themselves, there’ll be the chance to see some of the stars of the music, in photographs, paintings, cartoons and sketches.

The ‘jazz age’ was an era when the running in making the music was still being made by Americans, both black and white, and until our own Musicians’ Union made it increasingly difficult for US visitors to perform here in the ‘30s, many of the great pioneers worked in Britain. So we’ll see how British ![]() photographers and artists depicted such American giants of the music as Duke Ellington, Fats Waller, Coleman Hawkins, Benny Carter, Adelaide Hall, Elizabeth Welch and other black artists. And we’ll equally have the opportunity to see images of such white players as Paul Whiteman (whose musicians made the headlines by arriving at the Royal Albert Hall by bicycle for a concert during the 1926 General Strike), Ted Lewis, and multi-instrumentalist Adrian Rollini. Yet this does not mean that Britain did not create its own jazz heroes and heroines, from bandleaders familiar from the BBC such as Jack Hylton and Henry Hall to black players such as Ken “Snakehips” Johnson or Rudolph Dunbar.

photographers and artists depicted such American giants of the music as Duke Ellington, Fats Waller, Coleman Hawkins, Benny Carter, Adelaide Hall, Elizabeth Welch and other black artists. And we’ll equally have the opportunity to see images of such white players as Paul Whiteman (whose musicians made the headlines by arriving at the Royal Albert Hall by bicycle for a concert during the 1926 General Strike), Ted Lewis, and multi-instrumentalist Adrian Rollini. Yet this does not mean that Britain did not create its own jazz heroes and heroines, from bandleaders familiar from the BBC such as Jack Hylton and Henry Hall to black players such as Ken “Snakehips” Johnson or Rudolph Dunbar.

The photos and paintings will give us a sense of how people dressed and danced to jazz, dance being the social entertainment related to the music that continued right through the period of the exhibition. We can also see ![]() how jazzy designs and imagery permeated many other areas of the visual and tactile arts. From wallpaper to curtains and from teapots to drinks cabinets (and their contents), this wild syncopated music touched every area of art and design.

how jazzy designs and imagery permeated many other areas of the visual and tactile arts. From wallpaper to curtains and from teapots to drinks cabinets (and their contents), this wild syncopated music touched every area of art and design.

What is so special about this exhibition is the chance to see these objects in the broader context of a music whose pros and cons grabbed the national imagination and even infiltrated literature. So on the one hand there was Evelyn Waugh’s Gilbert Pinfold who “abhorred plastics, Picasso, sunbathing and jazz”, or novelist Aldous Huxley who described jazz as “a brimming bowl of hogwash” – and on the other hand Stella Gibbons’ character Mrs Beetle in Cold Comfort Farm who enthusiastically trained her four grandchildren into “one of them jazz bands” so that they could earn the then-princely sum of six pounds a night!

The Bulldog Trust and The Arts Society present The Age of Jazz at Two Temple Place, London, WC2R 3BD from 27 January– 22 April 2018. Admission is free.

twotempleplace.org

To pre-order the exhibition catalogue please visit theartssociety.org/age-of-jazz

Image: H Clark, Jazzing in England from Pan, 27 March 1920, page 19.

About the Author

ALYN SHIPTON

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition