This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

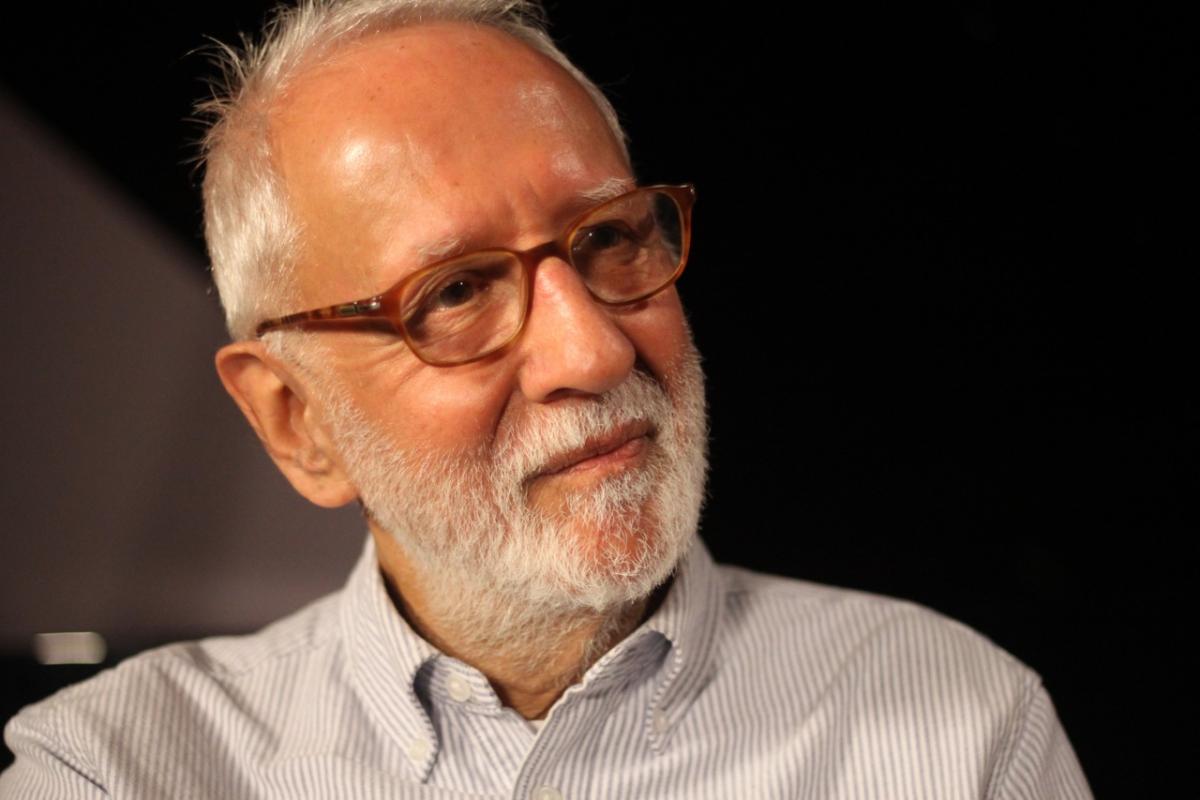

The Arts Society Lecturer Daniel Snowman: My life in art

The Arts Society Lecturer Daniel Snowman: My life in art

7 Jan 2019

Daniel Snowman is a writer, broadcaster, lecturer and senior research fellow at the Institute of Historical Research, University of London. He has given well over 600 lectures to The Arts Society since joining the Directory 20 years ago.

From the social history of opera to the cultural impact of the ‘Hitler émigrés’, you cover an exceptionally wide range of topics in your talks. Is there any one field in particular that fires you up the most – and why?

I always like to place the arts in their broad historical perspective. During the past few years, as we’ve marked the centenary of World War I, I have lectured widely on the relationship between war and the arts, from the triumphs and tragedies of Napoleonic times, the revolutions of 1848, Crimea, Italian independence and the poets of World War I to Guernica, Olivier’s inspiring Henry V and the rebuilding of Coventry Cathedral. And now, with the 80th anniversary of the outbreak of World War II coming up in September, I find myself returning more and more to the huge cultural impact – in all the arts – of the refugees from Nazism.

After delivering some 600 talks, you must have a few anecdotes up your sleeve about doing so?

Very few I can reveal publicly! But let me tell you about how I came to be an Accredited Lecturer back in 1998.

I had never heard of the organisation when a friend suggested I apply to become a lecturer. I duly did so, and was told to prepare a short illustrated talk to present before a judging panel. My most recent book, co-edited with Asa Briggs, was about art and culture around previous turns of centuries, so I browsed through the text, made a few slides of late Elizabethan miniatures, Gillray cartoons, Beardsley prints, etc, and duly gave my talk. After a few polite questions I was asked what other topics I might offer if selected, and I mentioned something about opera – the most multimedia of all art forms. This set off a fierce debate among the panellists as to whether music qualified as one of the ‘decorative and fine arts’. ‘Then what about the history of gardens?’ one member shot across the bows as I looked innocently on...

Happily, I was accepted, gave dozens of talks during my first year (1999) about ends of centuries, and have ranged far and wide ever since.

And some top tips on how to deliver a successful lecture?

I wouldn’t presume to tell my fellow lecturers how to do their job!

For myself, I always try to do the following:

1. Introduce the topic with an engaging summary of the lecture as a whole: the structure, the central topic and theme, and what we are going to try and establish by the end.

2. Give milestones along the way: ‘So far, we have done such and such. And now, I want to turn to...’

3. Don’t try and pack in too many images. Less is more, and gives your audience a better chance of taking in what it is you are trying to communicate.

4. Look up and speak clearly in the language of everyday discourse. No unnecessary passive verbs, abstract nouns or academicisms.

5. Towards the end, sum up the overall theme, remind listeners of the highlights – and try to conclude with an attractive rhetorical flourish.

6. Never overrun!

You’ve led over 50 tours to the world’s cultural capitals. Any ‘hidden gem’ you’ve encountered that many people might not know about?

Next time you are in Prague, head towards the Czech border with Austria and you will reach Český Krumlov in southern Bohemia. Český, looming forbiddingly over the narrowing Vltava River (made famous by Smetana), is the site of one of the great European castle cities, its origins going back to late medieval times. And in one of its myriad courtyards lies the jewel of the entire complex: its Baroque theatre.

It was in the 1770s and 1780s that the Český theatre achieved its true glory, with its sophisticated backstage system of ropes and pulleys, moveable footlights and scene-changing technology, as it resonated to the sights and sounds of the latest Italian opera seria and opera buffa, French opera and German Singspiel. It fell into decline in the 19th century, but today, after careful restoration, it is open to visitors: ‘a veritable Aladdin’s cave to any visiting theatrical antiquarian’, as one visitor put it recently.

Image: William Blake, Newton 1795–c.1805. Tate

Which 2019 arts or cultural event are you most looking forward to?

Very difficult to choose! But one of the most revealing, in this anxious, uncertain yet (dangerously) exciting world of ours, might well be the exhibition of artworks by that multitalented, often agonised herald of Romanticism William Blake, opening at Tate Britain next September. Blake was not only a masterly painter and printmaker, but also a poet capable at times of holding his head high alongside such younger contemporaries as Coleridge, Byron, Shelley, Keats and Wordsworth. Living through, and influenced by, the ideas of the American and French Revolutions, Blake was also something of a religious and moral visionary (and rebel), as many of his paintings reveal. And, as the Tate points out, his personal struggles in a period of political terror and oppression, his technical innovation, his vision and his political commitment have perhaps never been more pertinent. I’ll certainly want to be there: bring me my chariot of fire!

SIGN UP

for our monthly free newsletter, full of news, offers, exhibitions and book reviews: theartssociety.org/signup

DIP INTO

The Arts Society Magazine, out four times a year, which includes the latest in the arts world titles

About the Author

The Arts Society

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition