This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

The artist making art from plastic pollution

The artist making art from plastic pollution

2 Aug 2019

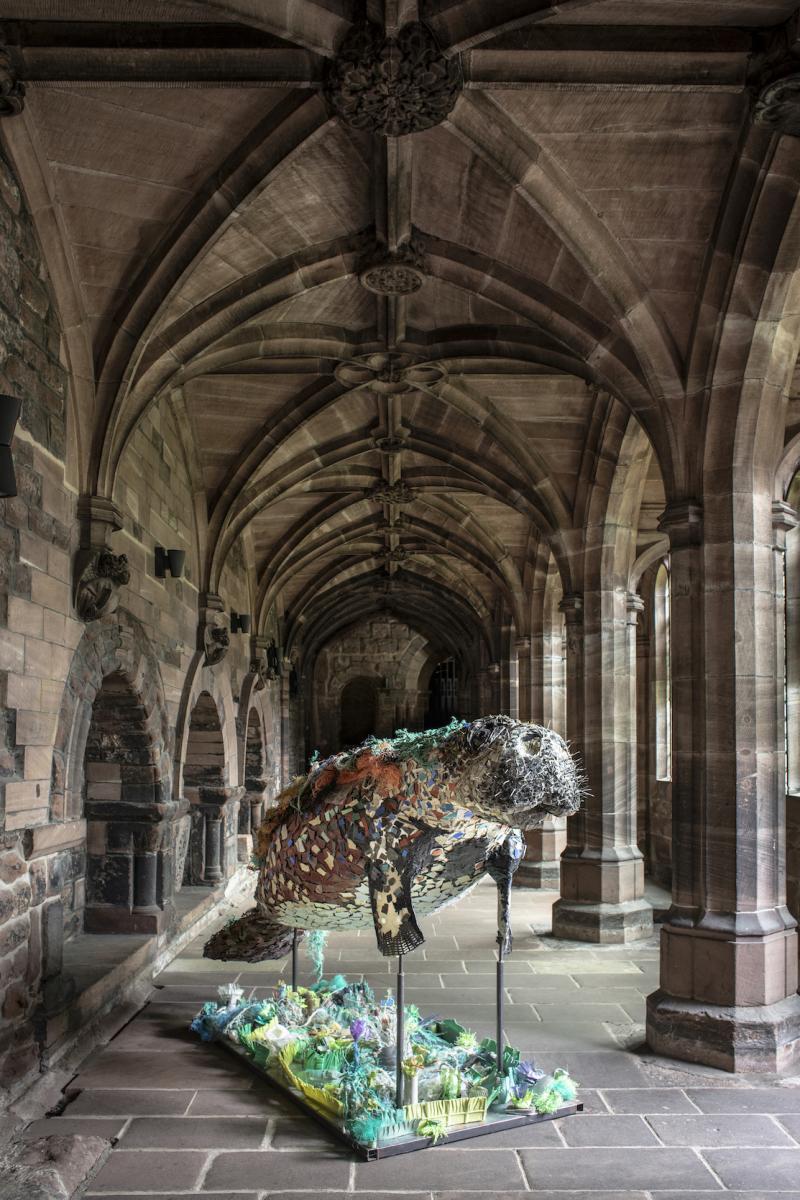

Head to the cloisters of Chester Cathedral to catch Saving the Deep – artist Jacha Potgieter’s powerful response to the plastic pollution in our seas and the threats to our precious marine wildlife.

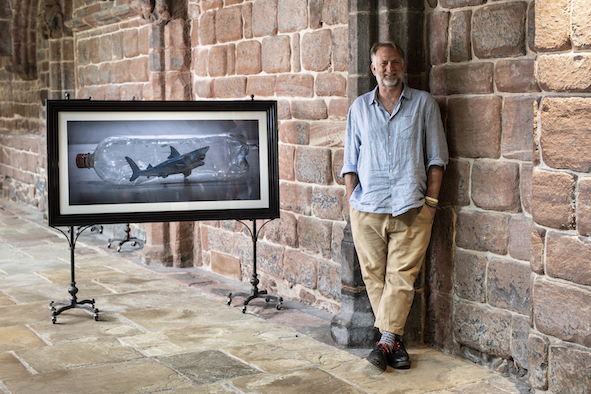

Artist Jacha Potgieter at Chester Cathedral with his photographic artwork. © Cristian Barnett

Artist Jacha Potgieter at Chester Cathedral with his photographic artwork. © Cristian Barnett

Born in South Africa, artist and conservationist Jacha Potgieter now works from a studio in North Wales. His latest project is an installation at Chester Cathedral, as part of the cathedral’s 2019 season on the theme of ‘waves’ – a series of initiatives to raise awareness of the importance of water to our world.

The installation is made up of 12 arresting sculptures, which were created using plastic waste washed up on the beach at Criccieth, all collected by the artist on just three visits. Now his monk seal and manatee, krill and turtle have settled in haunting fashion in the cathedral’s spaces. Each work carries a hard-hitting message on plastic pollution and its threat to marine life.

Here we show five of the works, and Potgieter reveals the shocking stories behind each one to Sue Herdman, Editor-in-Chief of The Arts Society magazine.

Shredded albatross

‘This sculpture is my response to a harrowing image that has been circulating on social media and in wildlife documentaries for the past few years. It shows the corpse of an albatross with plastic fragments among its feathers and skeleton. The photograph was taken on the Midway Atoll in the North Pacific Ocean and has made the seabird an icon of the plastic pollution problem.

‘Over the past decade or so, scientists and conservationists have been investigating and recording the impact of plastic debris on seabirds. I’ve read that the conclusion is that by 2050, 99% of seabirds will have plastic in their stomachs, having been attracted to the algae that grows on plastic particles floating on the sea’s surface. Mistaking this for food, they return to their nests to feed their young. The young birds choke on the inedible pieces, or, as their stomachs fill with plastic, starve.

‘If you watched the recent Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall and Anita Rani BBC documentary War on Plastic with Hugh and Anita, you may have clocked the statistic that every 60 seconds the equivalent of a rubbish truck full of plastic is emptied into the world’s oceans. It’s terrible facts like these that have driven me to create these sculptures.’

Threatened manatees

‘I love this image of my manatee sculpture, shown here in the cloisters of the cathedral. It almost appears to float in the space. I find manatees strangely beautiful. They are large herbivores, and you’ll find them in shallow, marshy coastal areas and the rivers of the Mesoamerican reef system. They’re gentle creatures, full of curiosity.

‘I learnt from the World Wildlife Fund website (www.worldwildlife.org), that manatees are facing all sorts of threats. Because of their inquisitive nature, they often approach boats and can be unintentionally killed or injured after getting caught in fishing nets. They are also prone to boat collisions when in shallow coastal areas.

Then there are issues surrounding coastal developments, which often threaten their shallow water habitats. Finally, there is nutrient pollution. Manatees depend on sea grasses and other near-shore ecosystems for food and shelter, and these areas can be affected by chemical run-off from agricultural land, which pollutes coastal ecosystems and threatens manatee habitats.

‘Today, this lovely sea mammal is listed as vulnerable on the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s red list, and the manatee population is decreasing. My sculpture, made entirely from plastic waste that I’ve collected, appears to float over a sea bed of plastic. My message is that, by their presence, these enigmatic marine creatures help to keep a vital balance of vegetation in the ecosystems they inhabit. It is said that their health is an indicator of the overall health of the marine ecosystem.’

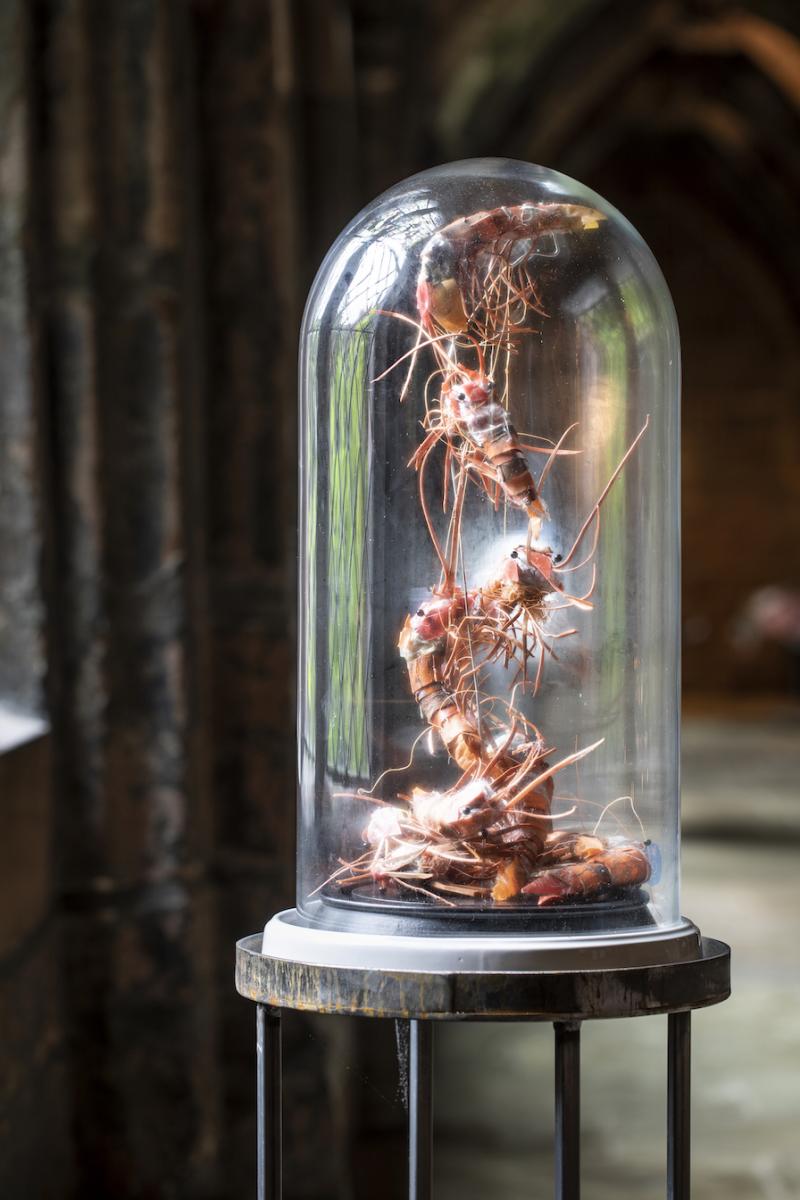

The mighty krill

‘Placed in a dome, my krill sculptures are larger than life so visitors to the cathedral can really see them, but in reality, they are tiny – not much bigger than a paper clip. There is something about putting the sculptures within the dome that captures the light within the cathedral, making them appear to be underwater.

‘Although small, krill play such an important part in the food chain. Without them, the earth’s ecosystems would be unbalanced. On the National Geographic’s website (nationalgeographic.com) there is the latest information on krill. It’s where I learnt that recent studies show Antarctic krill stocks may have dropped by 80% since the 1970s. Scientists attribute these declines partly to ice cover loss caused by global warming.

‘There are 85 known species of krill. One of the largest is the Antarctic krill, and at peak times of the year giant swarms of krill have been visible from space, as they float on the surface of the ocean. They are one of our world’s wonders.’

Beautiful bluefin

‘When researching the bluefin tuna for this exhibition, I discovered valuable information from the WWF website: worldwildlife.org. I recommend everyone to go there too, to find out more about these, the largest tunasin the world.

‘They are the most extraordinary fish, living – if they are allowed to – up to 40 years and migrating across oceans. And, as with all marine creatures, they play a key part in the ocean’s environmental balance. In fact, they are the top predator of the marine food chain.

‘There are three species of bluefin: Atlantic (the largest and most endangered), Pacific and Southern. It is the Atlantic bluefin that is particularly sought-after for making sushi and sashimi in Asia. I learnt from the WWF that one single fish actually went for more than $1.75 million in 2013. Excess and illegal fishing are huge threats to the survival of the bluefin. I wanted to highlight the sushi story, so I built my big plastic bluefin to appear to be floating over four small portions of sushi, the ‘sushi’ itself being made, of course, from plastic waste.’

The tortured turtle

‘We live in such a disposable society now, with 95% of plastic packaging being discarded after a single use. When coming away from one of my three beachcombing trips to collect plastic for this installation, I spotted a skip full of plastic toys that had just been thrown away. I used those to make this turtle. In doing so, I wanted to highlight plastic’s short ownership in relation to its long-term existence.

‘My turtle is inspired by the hawksbill. It’s a turtle that is mainly found in tropical oceans, predominantly in coral reefs. Sea turtles are, again, a fundamental link in marine ecosystems and help maintain the health of coral reefs and sea grass beds.

‘The threats to hawksbills – and other sea turtles – include the loss of nesting and feeding habitats, excessive egg collection, fishery-related injuries, pollution and coastal development. Nearly all species of sea turtles are now classified as endangered, which is terrible.

‘My turtle here, with a plastic bag in its mouth, shows one common danger. Turtles mistake floating plastic for food such as jellyfish – and I’ve read that they can think that plastic fishing nets are seaweed, with awful results once they ingest the plastic.’

See

Saving the Deep at Chester Cathedral until 31 October. Entry is free.

Check the website for details: chestercathedral.com

Find out more about Jacha Potgieter’s work at jacha.co.uk

Photographs by Cristian Barnett: crisbarnett.com

About the Author

Sue Herdman

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition