This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

Art behind bars

Art behind bars

18 Oct 2019

How can art make a difference to the life of an offender? Arts Society Lecturer Angela Findlay, who has spent years teaching in prison institutions, reveals her findings.

W.T.F, HM Prison Dovegate, Doughty Street Chambers, Audience Choice Platinum Award and the James Wood QC Bronze Award for Painting, 2016 Koestler Awards

W.T.F, HM Prison Dovegate, Doughty Street Chambers, Audience Choice Platinum Award and the James Wood QC Bronze Award for Painting, 2016 Koestler Awards

‘I can’t believe I did that,’ a young inmate said of the result of a mosaic project. You could almost see the next thought formulating: ‘If I can do that, what else can I do?’ Over a five-week art project, he had reaped the pleasures and benefits of perseverance, teamwork, solution-seeking and overcoming the ‘quick-fix’ mentality that sees crime as a shortcut. He had practised the self-discipline required for handling tools and sensitive materials, and had felt the pride of achieving something good and beautiful. The project had raised his self-esteem, filled him with positive feelings and opened his eyes to possibilities for his future.

Members of The Arts Society will know how the arts have the capacity to communicate ideas, demonstrate beauty and skill, and provide purpose, meaning or even transcendental experiences. The arts speak to the creative side of our humanity and inspire us to strive for that which lies beyond the everyday. They invite us to look at and think about the world and our place in it in new ways. Are these not the very qualities we need most in our criminal justice system?

Pop Arty Brush Stroke, HM Prison & Young Offender Institution Stoke Heath, Long Family Commended Award for Painting, 2017 Koestler Awards

As an artist who has worked in prisons both in England and Germany, I am baffled by the illogic of locking people up in increasingly overcrowded, filthy conditions with nothing purposeful to do, only to then eject them back into society with the expectancy that they will somehow be changed for the better. I am equally concerned that the arts, with their known and proven benefits, are not given a prominent role in the Prison Service’s self-declared mission to help offenders ‘lead law-abiding and useful lives on release’. With reconviction rates of 48% within a year of release, or 64% if sentences are less than 12 months; with cuts in funding, staff and art provisions; and with dramatic rises in sexual assaults, violence and self-harm, our prisons are currently a litany of waste: a waste of time, a waste of money but, worst of all, a waste of human potential.

Lovers, North London Clinic, Painting, 2018 Koestler Awards

FINDING A WAY

The Hungarian-born Jewish émigré writer Arthur Koestler (1905–83), who converted to communism and later rejected it, experienced periods of imprisonment in France, Spain and England. Exposure to prison life led him to be one of the first people to articulate that: ‘The prisoner’s worst enemy is boredom, depression, the slow death of thought.’

When he founded Koestler Arts in 1962, now the UK’s best-known prison charity, he believed art would help to not only make a prisoner’s life more bearable, but also to uncover hidden talents, equip them with tools with which to build a new future, and stimulate their minds and spirit. For the first Koestler Exhibition that year, there were 200 artistic entries. Now there are over 7,000, pan-arts, with over 2,000 awards granted, judged by professional artists and figures such as Jeremy Deller, Emma Bridgewater and Louis Theroux. Of recent entrants, 55% said that experiencing arts in prison had helped them keep free from crime, while 91% cited an improved self-confidence.

In 1986 I was locked in an exercise yard in Sydney’s Long Bay prison to work on my first mural project with two Brazilian cocaine smugglers, a bank robber and a murderer. I was not scared. Like Koestler, I believed that creativity was the antidote to destructivity and that the arts were best placed to draw out a person’s potential. As I worked out how to apply my trade in prisons, a wise artist told me: ‘The work of art is not what happens on the piece of paper or canvas, it’s what happens in the human soul.’ He used the word ‘soul’ in the broadest sense. Over the next 20 years, I witnessed hundreds of human souls embarking on journeys of transformation. From simple colour ‘warm-up’ exercises, it was possible to go on to reveal bottomless pools of untapped creativity.

Spontaneous Fusion, HM Prison Standford Hill, Bronze Award for Painting, 2018 Koestler Awards

Spontaneous Fusion, HM Prison Standford Hill, Bronze Award for Painting, 2018 Koestler Awards

As human beings, we all feel. But for so many offenders traumatic, abusive and dysfunctional childhoods, limited education or drug abuse all cause a cutting off from, or a violent reaction to, uncomfortable feelings such as inadequacy, fear, anger or shame. The arts help us to feel and heal. Just as exercise is vital for the healthy physical body, so the arts offer essential arenas for self-expression, self-exploration and emotional literacy. Engaging in creativity helps turn chaos into some sort of meaningful, useful or beautiful order. And its positive impact is not restricted to the participants.

POWERFUL TOUCHPOINTS

Encouraged by an enlightened prison governor, the painting of the walls of Cologne Prison not only brightened a grey, oppressive atmosphere, it transformed relationships between those who lived and worked there. A 200-metre corridor, along which prisoners and officers would shuffle with eyes to the ground, became, when painted in rainbow colours, a space of animated conversation. ‘I like this turquoise,’ one might say, ‘it reminds me of my front room.’ ‘The yellow makes me feel like I’m on holiday,’ the other might reply. Suddenly, these were just two men exchanging opinions and expressing how they felt. Often it went further. On seeing a mural a prison officer might say, ‘I had no idea that John was capable of that; it’s brilliant.’ In that moment, John became a creative force for good, rather than just another number to lock away.

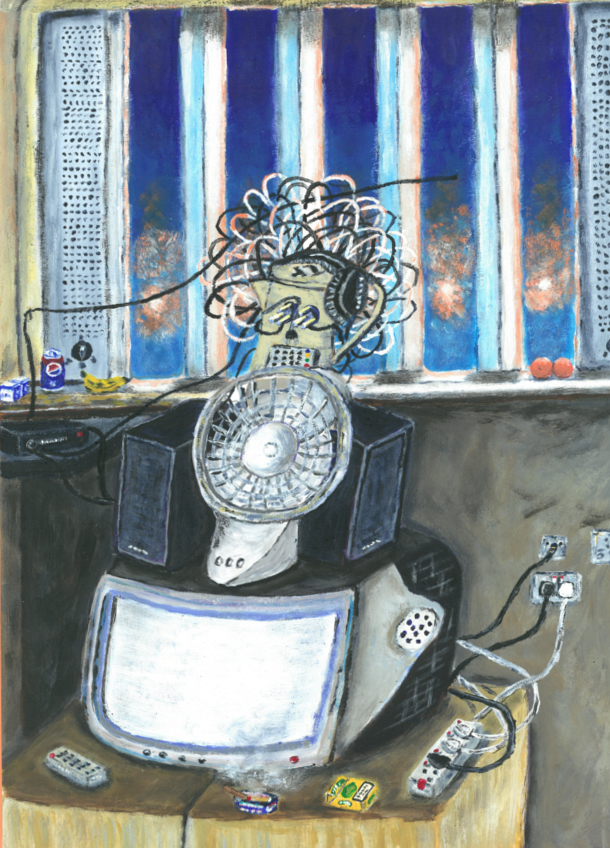

Collective Electronica, HM Prison Gartree, Painting, 2018 Koestler Awards

Collective Electronica, HM Prison Gartree, Painting, 2018 Koestler Awards

If you love art, it takes little imagination to see the vital role it plays for people who are incarcerated. Twenty-three hours a day of boredom, daytime TV, cramped conditions and bad food may feel like effective and deserved punishment. But it leads to catastrophic statistics and cycles of failure. It is in all our interests that the transformative process of art is integrated in criminal justice settings. There are huge challenges. I felt obliged to give up my work when understaffing prevented officers from even delivering course participants to the art room. Now I lecture, highlighting the ways in which the arts can incentivise people to want to change, because wanting to change is the first step in bringing about real, and lasting, difference.

Angela Findlay is an artist, writer and Arts Society Lecturer. As arts coordinator to Koestler Arts (2002-6), she founded the Learning to Learn Through the Arts scheme and recently advised the Ministry of Justice on the inclusion of the arts in its education policies.

SEE

Koestler Arts’ 2019 exhibition, Another Me, curated by award-winning saxophonist and MC Soweto Kinch, at London’s Southbank Centre; until 3 November; koestlerarts.org.uk

Large groups can book a private tour of the exhibition. Contact charis@koestlerarts.org.uk

Get Involved

Contact the education or arts department of your local prison to offer to support a project, or donate materials or grant funds towards existing ideas.

Support the work of the Prison Reform Trust or the Howard League for Penal Reform.

Find out how to sponsor an award, or to support Koestler Arts outreach and mentoring work, by contacting support-us@koestlertrust.org.uk

SIGN UP

This feature is published in the autumn issue of The Arts Society Magazine, available to all members.

About the Author

Angela Findlay

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition