This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

5 things to know about The Singh Twins

5 things to know about The Singh Twins

25 May 2022

The Singh Twins have created a unique genre in contemporary British art and deliver challenging narratives with their works. Sue Herdman met them at their exhibition, Slaves of Fashion, to discover more about their extraordinary works and how they make them

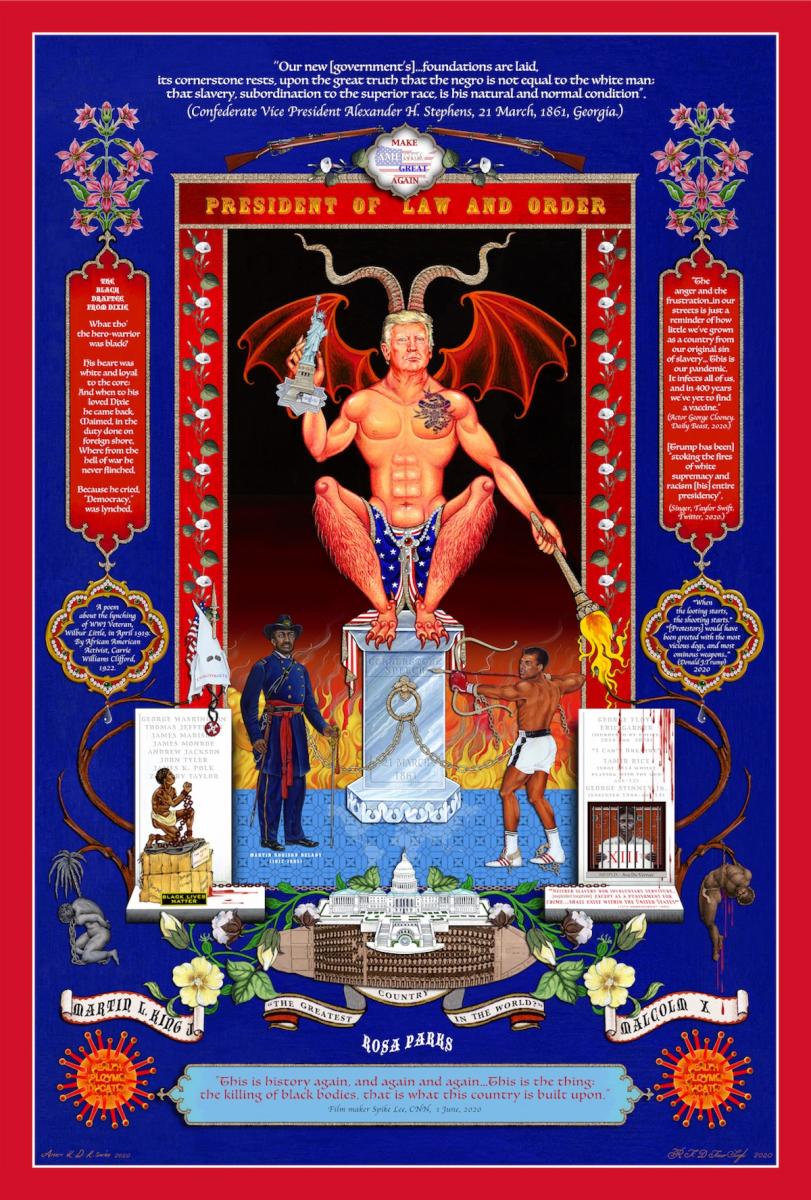

Get Your Knee off Our Necks © The Singh Twins

The Singh Twins are known for…

…their distinctive approach to art, fusing Indian traditional and contemporary Western influences. Working together, they use a flattened perspective, as in ancient Indian miniature paintings, and lace their works with electrifyingly modern social, cultural and political themes.

There is seriousness, wit and mischief in their art. They channel the past and survey the current: you’re as likely to spot Daniel Defoe or Elizabeth I in a Singh Twins painting as you are the marathon-running supercentenarian Fauja Singh, pop star Madonna or, as above, Donald Trump.

Shown here is The Singh Twins’ Get Your Knee Off Our Necks, made in response to the killing of George Floyd. Imagery within this work denotes a nation built on the slave trade. The tattoo on Trump’s torso comprises narcissus flowers. He grips a gagged Statue of Liberty – an allusion to a denied right to protest. When asked as to why the artists chose to show Trump in such buff, toned form, they respond: ‘It’s an image of how we imagine he sees himself.’

Their work is meticulous and they embrace multimedia, using digital alongside the paintbrush. They also embrace filmmaking, poetry and writing. Theirs is an art that is impossible to pigeonhole. It is about craftsmanship and beauty, global politics and issues, human connections, hidden histories, shared heritage and identity.

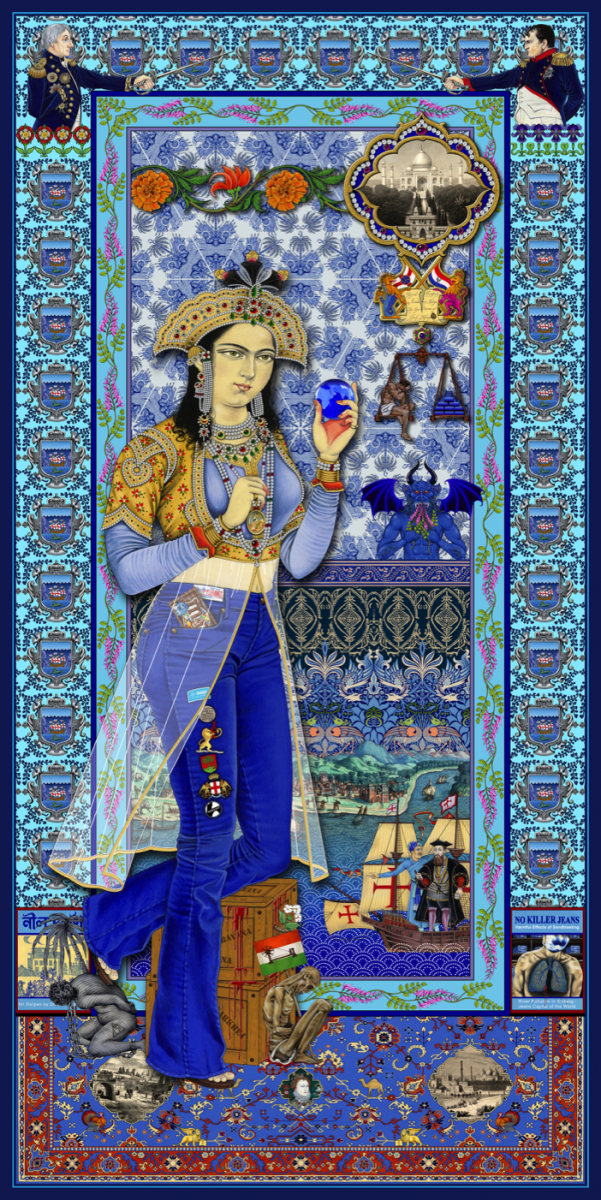

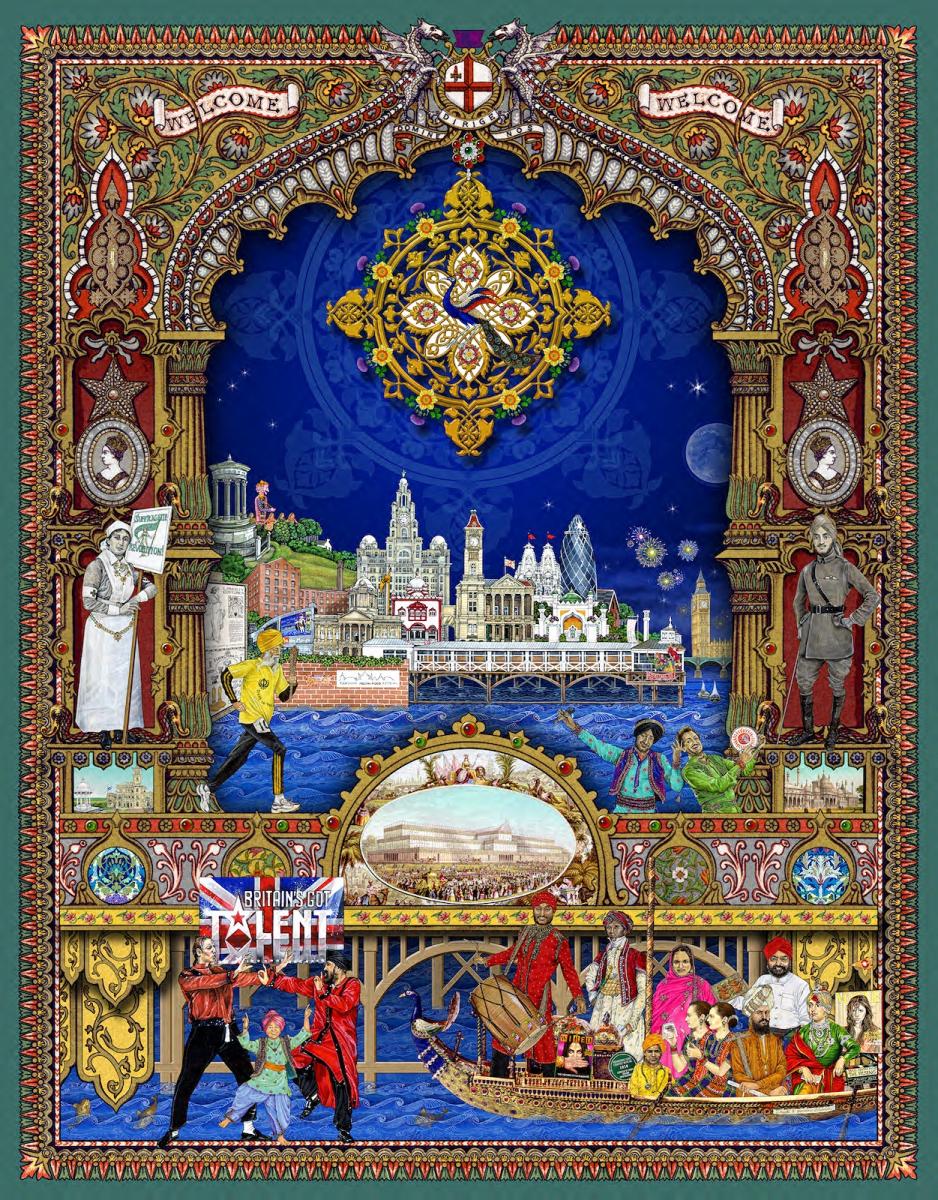

Indigo: The Colour of India, a life-sized digital artwork, © The Singh Twins

They love detail

Studies have shown that, on average, visitors to a gallery spend eight seconds in front of an artwork. Be prepared then, on encountering The Singh Twins’ art, to lose track of time. Such is the detail – and the stories to absorb – you can spend half an hour on just one work. Each is the result of hours, weeks or even months of research. The Twins are academic artists. They haunt galleries and museums, libraries and the internet, drilling down on their latest themes.

The Singh Twins: Slaves of Fashion has been four years in the making. Ostensibly about Indian textiles and a colonial past, it’s also a political show that examines the legacies of Empire, conflict, enslavement and luxury consumerism in today’s world.

Let’s take one work from the exhibition, shown above, to examine the features that make the whole. Called Indigo: The Colour of India, this life-sized digital piece explores the troubled story of indigo’s links to slavery and conflict. It shows the Indian queen – Mumtaz Mahal – wearing that iconic item of Western clothing: a pair of blue jeans. Far from being Western, the origins of denim go back to the India of the 16th century, to the port town of Dongri, where the hardy fabric was produced to be worn by sailors (the name ‘Dongri’ is where the word ‘dungarees’ came from). But what else do we see? Peer closely and messages about the human and environmental costs of producing indigo emerge.

‘Our work represented all the taboos of contemporary Western art in that it was decorative, figurative, narrative, small-scale, non-individualistic and coming from a non-European tradition’

Called ‘blue gold’, indigo was so valuable it was used as currency to buy slaves (featured here at Mumtaz’s feet). And during British colonial rule in India, farmers were forced to grow indigo rather than food crops, leading to the starvation alluded to by the other figure at her foot. In contrast, the opulent Taj Mahal that Shah Jahan built in memory of Mumtaz features too (top right), its location, the city of Agra, a main production site for indigo.

Keen magpies of any appropriate archival material, the Twins incorporate elements into this work: spot the 15th- to 16th-century textile fragment of indigo-dyed cotton from Gujarat, found in Old Cairo, and the Peacock and Dragon motif by William Morris, both sourced from the V&A Collection. See, too, a beautiful 16th-century hand-coloured engraving of modern-day Kozhikode (from their own collection).

Look out, too, for the message on the lower right: a masked torso with blue-grey lungs and the message ‘No Killer Jeans’ – a rally cry against the harmful effects of the sandblasting processes used to make modern-day stonewashed denims.

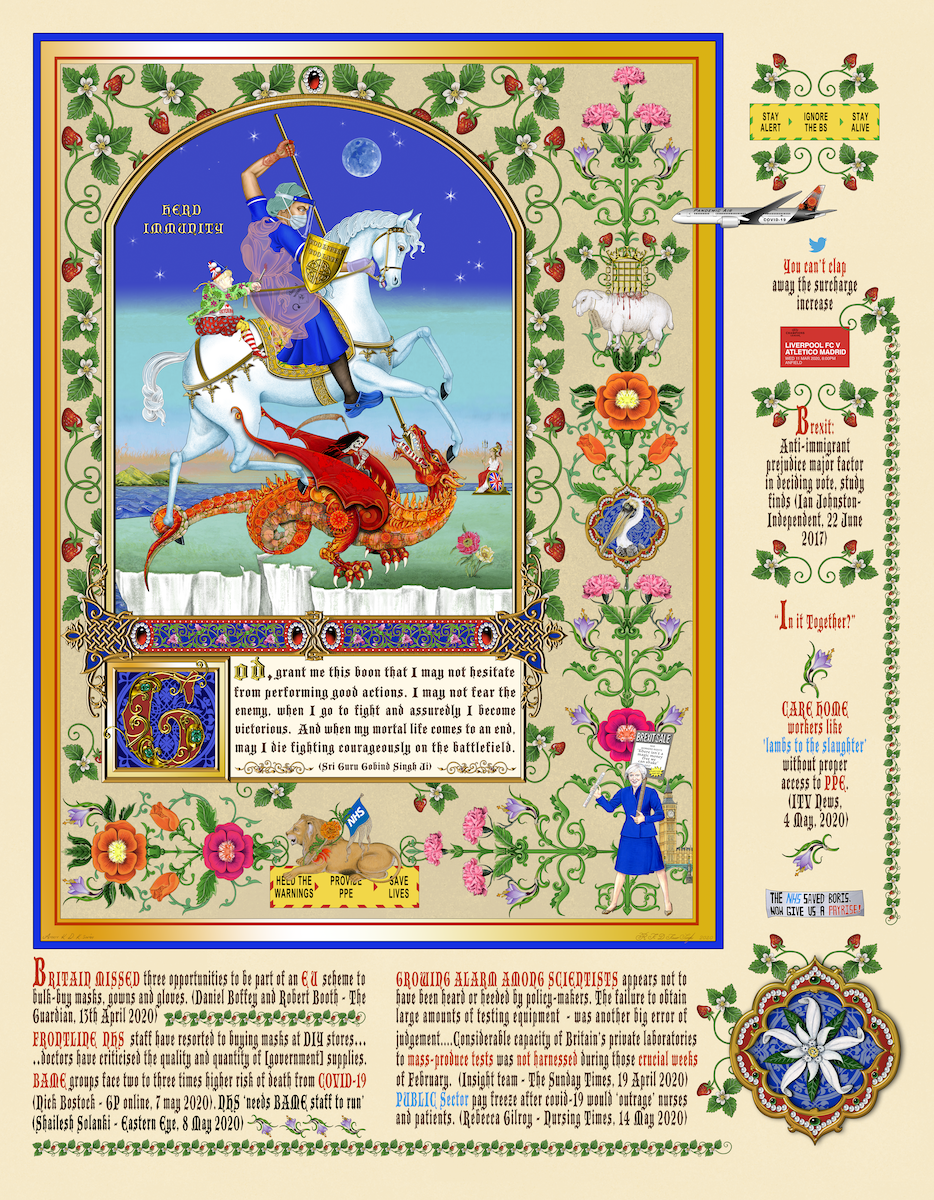

NHS v Covid-19: Fighting on two Fronts © The Singh Twins

The Twins have a particular way of working

Once research is complete, they discuss the themes and stories they want to the fore. They then, with a focus that is identical, become two artists working as one. ‘We divide the work between us,’ they explain, ‘so the works in Slaves of Fashion could be said to be half-and-half ours.’

It’s not clear whose hand on each work is whose. From the meticulous miniatures to the huge digitally created fabric artworks that are stretched over giant light boxes, one suspects only each twin will ever know who, exactly, created what. Working together so closely, they say they are ‘always conscious of what the other is doing’. Occasionally, they admit, they might even ‘dabble a bit on each other’s work, when they aren’t looking’.

Whoever has created the work, it is always attributed purely to ‘The Singh Twins’. And, due to the level of detail, each one can take anything between 50 and 1,000 hours to execute.

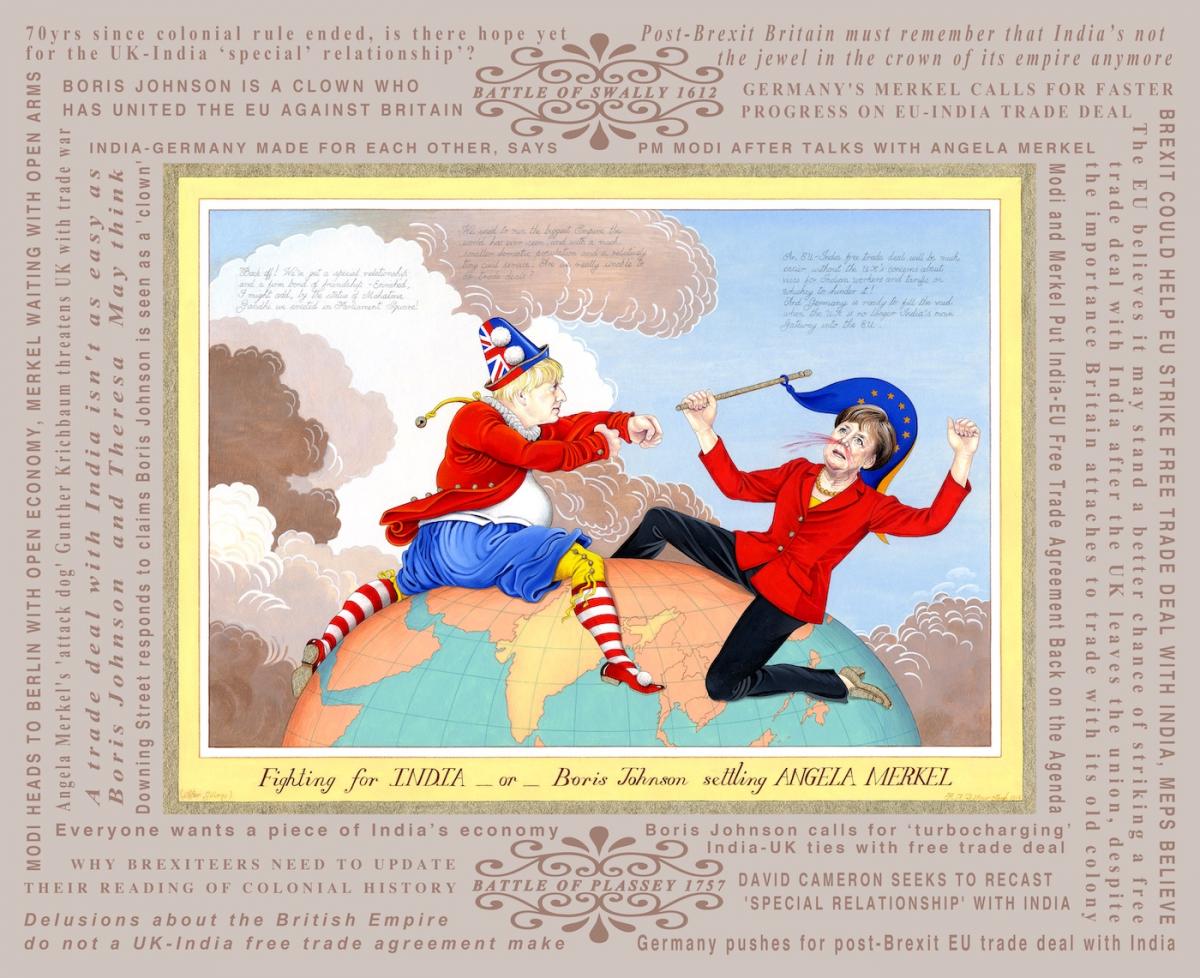

Fighting For India © The Singh Twins

They hadn’t always intended to be artists

Growing up near Liverpool, where they still live, the Twins originally wanted a career in medicine – their father is a doctor who came to the UK after the Partition of India in 1947. School tutors, recognising their talent, strongly advised art and in the end, reluctantly at first, they took a course in art as one part of a combined studies course at college.

From the earliest age they had shown real aptitude for drawing, ‘using the walls before we were given paper’. A key turning point came in 1980, when the family took a road trip to India. It was there that the Twins first encountered Indian miniature painting. They were fascinated by the symbolism and narrative within the works they saw, and the perfection with which they were painted. What they couldn’t understand was why the contemporary Indian art world had turned its back on such works, viewing them as out of date.

While still only teenagers, they began to teach themselves the techniques needed to execute works to the standard of the historical pieces they saw.

Middle panel of Rule Britannia: Legacies of Exchange © The Singh Twins

Their path to current acclaim hasn’t been smooth

As students, the passion that The Singh Twins had for that ancient art of Indian miniature painting received derision and kickback. Art tutors dismissed their focus on the genre as backward. ‘It seemed,’ the Twins have said, ‘that our work represented all the taboos of contemporary Western art in that it was decorative, figurative, narrative, small-scale, non-individualistic and coming from a non-European tradition.’

They were under pressure to conform, to look to Western aesthetics. Not only was their work considered too traditional, but, due to the marked similarity of their styles, it was also deemed ‘unacceptable’. They were urged to develop individual styles. But those critics had perhaps not considered the power that comes from duality, nor the strength of The Singh Twins’ conviction in their art. Some – including themselves – have alluded to their stubbornness. Others would call it courage. In response they turned their practice as artists into a political statement.

‘Their work champions traditional and non-Western aesthetics as valid forms of expression within contemporary art’

Celebrating their shared approach to art and revelling in their lack of need for complete individuality, they dress identically. In fact, viewed together, they are almost an artwork in themselves. They work and exhibit together. Rather than being known by their names, Amrit and Rabindra Singh, they insist on being referred to as The Singh Twins. And the style they have created they call ‘Past-Modern’. This, they say ‘champions traditional and non-Western aesthetics as valid forms of expression within contemporary art and acknowledges the connection that has always existed between past and present, East and West. Not least, the significant impact of traditional and non-European art and culture on Western modern art and society.’

Their convictions have paid off. Today their work sits in public and private collections across the world and is exhibited in top galleries. They have won multiple awards, diversified into poetry and filmmaking and been given an MBE by the Queen for services to the Indian miniature tradition of painting in contemporary art.

See

The Singh Twins: Slaves of Fashion at Firstsite, Colchester until 11 September; firstsite.uk

It is free to visit.

The exhibition will then travel to Norwich Castle Museum & Art Gallery, dates to be confirmed; museums.norfolk.gov.uk

Find out more at singhtwins.co.uk

About the Author

Sue Herdman

Sue Herdman is Editor of The Arts Society Magazine

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition