This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

5 moustachioed masterpieces for Movember

5 moustachioed masterpieces for Movember

1 Nov 2022

For 18 years men have been replacing the initial of the 11th month with an ‘M’, casting aside their razors for 30 days, and doing their bit for the global Movember movement. The so-called ‘Mo Bros’ unite to raise money for men’s health issues, including suicide prevention and prostate and testicular cancer. In honour of the moustaches that will be grown this month, Ciaran Sneddon looks at five artworks that champion facial hair

The Laughing Cavalier by Frans Hals, 1624. Credit: The Wallace Collection, London

The Laughing Cavalier by Frans Hals, 1624. Credit: The Wallace Collection, London

A highlight of Frans Hals’ career, and arguably the finest of any moustache ever put to canvas, The Laughing Cavalier is a beautifully misnomered portrait of the 17th century. Showing neither a cavalier, nor one that is laughing, at first glance the work seems to dance with excitement and verve. It is only on closer inspection that the muted colour palette can be fully absorbed. As Van Gogh is said to have commented: ‘Frans Hals must have had 27 blacks.’

Beyond the precise but whimsical brushes of facial hair, there is great dynamism in the cavalier’s uniform, albeit told mostly in black oils. The piece was a sensation among the public, entertained and troubled, no doubt, by its subject’s canny ability to stare back into the eye of the viewer, no matter where in the room they stand. Any Movember participant would be proud, and lucky, to produce such a masterful moustache of their own.

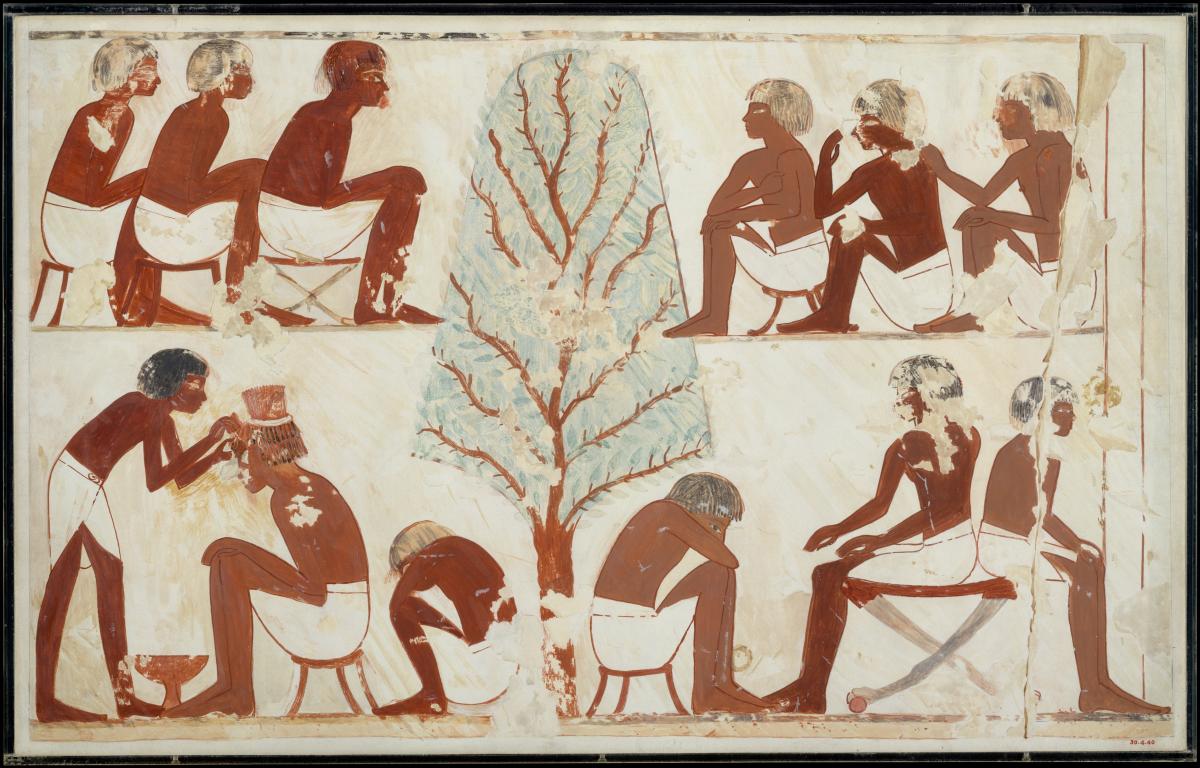

Barbering, Tomb of Userhat, a 1922 facsimile painted from an original at the tomb by Nina de Garis Davies. Credit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1930

Barbering, Tomb of Userhat, a 1922 facsimile painted from an original at the tomb by Nina de Garis Davies. Credit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1930

The art of shaving has evolved and transformed countless times. Modern men sign up to new subscription models for their technologically advanced razors, while peeling back the decades reveals the 1970s introduction of disposable blades, and the first popular safety razors some 70 years prior.

Going even further back in time takes us to a scene of community. This 1922 facsimile of an original image dating back to the 18th dynasty of ancient Egypt portrays men queuing up for their shave. It was found inside the tomb of a man called Userhat – a royal scribe and herald from the reign of Amenhotep II – at Thebes. Hair removal creams made of arsenic and lime, pumice scrubs, hot wax and copper razors all played their part in such early grooming regimes.

Marble statue of a bearded Hercules by an unknown artist, AD 68–98. Credit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of Mrs Frederick F Thompson, 1903

Marble statue of a bearded Hercules by an unknown artist, AD 68–98. Credit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of Mrs Frederick F Thompson, 1903

While the ancient Egyptians may have favoured the clean-shaven look, facial hair became a symbol of strength, honour, virility and wisdom for the ancient Greeks. The male Olympians all had impressive beards and moustaches, while thinkers of the time believed that longer beards implied a person’s brain had too much cleverness and was therefore having to push some intelligence out in the form of hair.

No surprise, then, that Hercules – the Roman version of the Greek hero Herakles – should be portrayed in such a hirsute manner. This marble statue is emblematic of a kind of sculpture that was used to honour the demigod. Part of a pair likely displayed at a large public bath, it was acquired among a collection of other ancient art by a 17th-century banker, the Marchese Vincenzo Giustiniani.

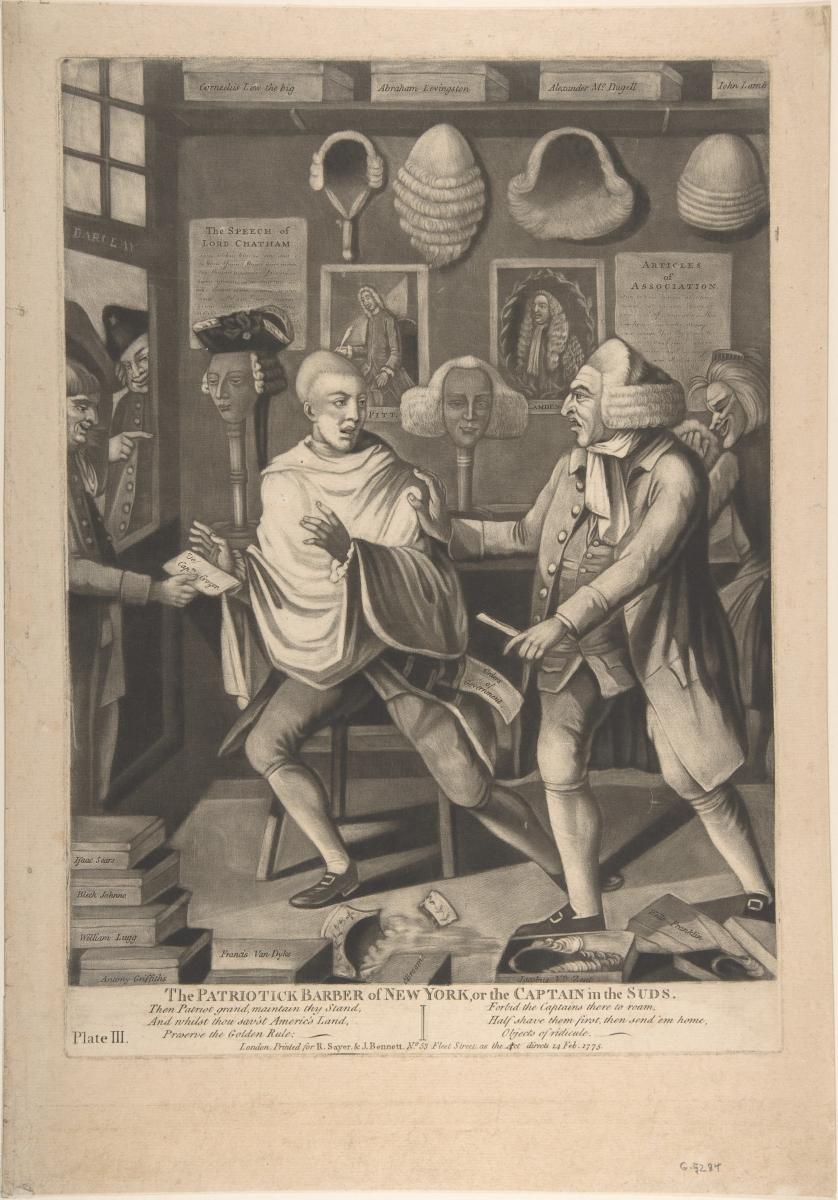

The Patriotick Barber of New York, or the Captain in the Suds, 1775, attributed to Philip Dawe. Credit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of William H Huntington, 1883

The Patriotick Barber of New York, or the Captain in the Suds, 1775, attributed to Philip Dawe. Credit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of William H Huntington, 1883

Given the clear significance of moustaches and beards within different cultures, the barbers of old are afforded a certain status and power through their gatekeeping of a particular skill. This is evidenced perfectly in this satirical mezzotint made in the months leading up to the American Revolution. The conflict between the British and the Americans may have yet to formally bubble over, but the independence-minded citizens of New York were quite happy to take matters into their own hands.

Here, we see Captain John Crozer, commander of a British ship, being recognised in the barber shop of Jacob Vredenburgh, a barber and member of the resistance group Sons of Liberty. Instead of starting a fight, Vredenburgh uses his position to mock his enemy. In text that accompanied the print when it was first issued in London, American patriots were reminded: ‘Preserve the Golden Rule; / Forbid the Captains there to roam, / Half shave them first; then send ’em home, / Objects of ridicule.’

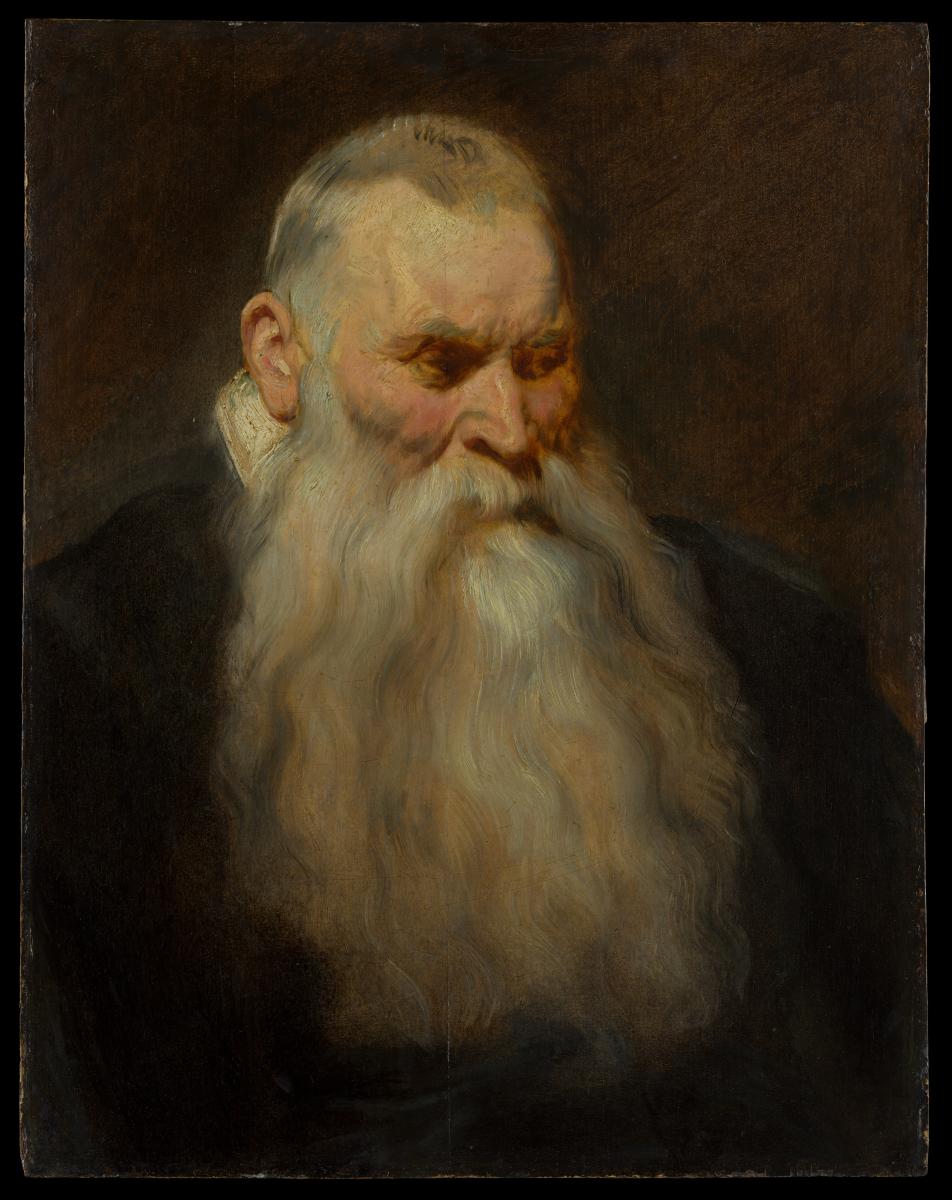

Study Head of an Old Man with a White Beard, Anthony van Dyck, c.1617–20. Credit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Egleston Fund, 1922

Study Head of an Old Man with a White Beard, Anthony van Dyck, c.1617–20. Credit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Egleston Fund, 1922

The muddiness of this portrait only heightens the softness and warmth of the subject’s impressive beard and moustache, which cascade down the centre of the image. Once believed to have been a piece by Peter Paul Rubens, a contemporary of Van Dyck who is credited with being an inspiration of sorts for the younger artist, it has since been recognised as one of Van Dyck’s early works, painted in his late teenage years.

Van Dyck is better known now for his stylings of another moustachioed man – Charles I, and his court. The Flemish painter imbued these works with great flattery, setting the bar for future royal portraits.

For more information on Movember click here.

About the Author

Ciaran Sneddon

Ciaran Sneddon writes for The Arts Society

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition