This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

5 marching artworks for March

5 marching artworks for March

6 Mar 2023

As 2023 moves onward, we set the pace with artworks about very different stories of marching

The third month has arrived, and with it the first signs of waning winter and strengthening spring.

It has been this way since the earliest Roman calendar, when Martius – the precursor to modern March – was a month of wild celebration and festivities. Named in honour of the warmongering god Mars, it marked a return to normality – or, in other words, that it was time for military campaigns to ramp back into gear after the relative peace of winter.

Movement is at the centre of this month’s selection of five artworks, too. While marching in March may involve two separate etymological roots, the former being a descendant of a word like mark, meaning boundary, the wordplay is irresistible. Here, we present five favourites that represent people moving forward en masse.

Maharaja march Maharaja Raj Singh in Procession with Members of His Court, attributed to Nihal Chand (1710–82). Credit: Cynthia Hazen Polsky and Leon B Polsky Fund, 2005/The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Maharaja Raj Singh in Procession with Members of His Court, attributed to Nihal Chand (1710–82). Credit: Cynthia Hazen Polsky and Leon B Polsky Fund, 2005/The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The concept of many people moving as one is seen in ceremonies the world over. Here, we see the stately Maharaja of Rajasthan followed by his entourage. Peer closely and you’ll see, below the Maharaja, and peeking out over the distance, his soldiers: a subtle sign, perhaps, of his strength.

Chand, who is credited as the artist, was at the forefront of Rajput painting, which became one of the dominant forms in the region during the 17th and 18th centuries. Using natural minerals, plants and shells, the artist would create vivid pigments to reproduce scenes from great legends or the everyday lives of the ruling classes.

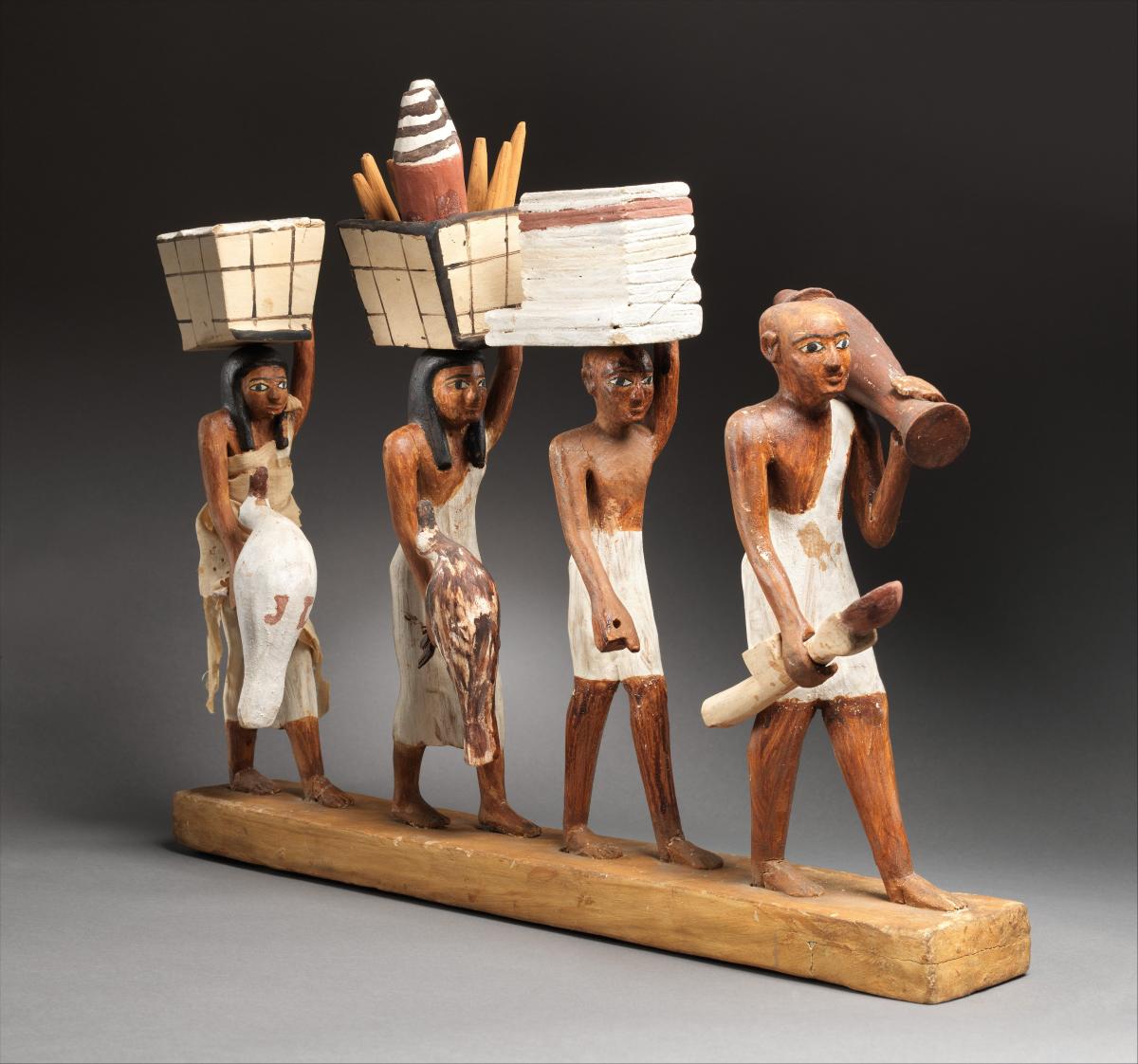

Model procession  Model of a procession of offering bearers, by an unknown artist, c.1981–1975 BC. Credit: Rogers Fund and Edward S Harkness Gift, 1920/The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Model of a procession of offering bearers, by an unknown artist, c.1981–1975 BC. Credit: Rogers Fund and Edward S Harkness Gift, 1920/The Metropolitan Museum of Art

This remarkably well-preserved model was found safely tucked away in a small chamber inside an Egyptian tomb in 1920. The tomb in question belonged to Meketre, a royal chief steward who served several leaders during the 11th and 12th ancient royal dynasties. In the years since his burial, his possessions and treasures had been plundered and ransacked, leaving what appeared to be a mostly barren room.

Herbert Winlock, an excavator, was overseeing a clear-up in the tomb in order to create a floor plan when the hidden chamber was found. Inside there were two dozen models. This one shows four individuals, likely Meketre’s children, walking in step, carrying items considered essential for a proper burial and funeral ritual, from a pile of linen sheets to a basket containing beer bottles and loaves of bread.

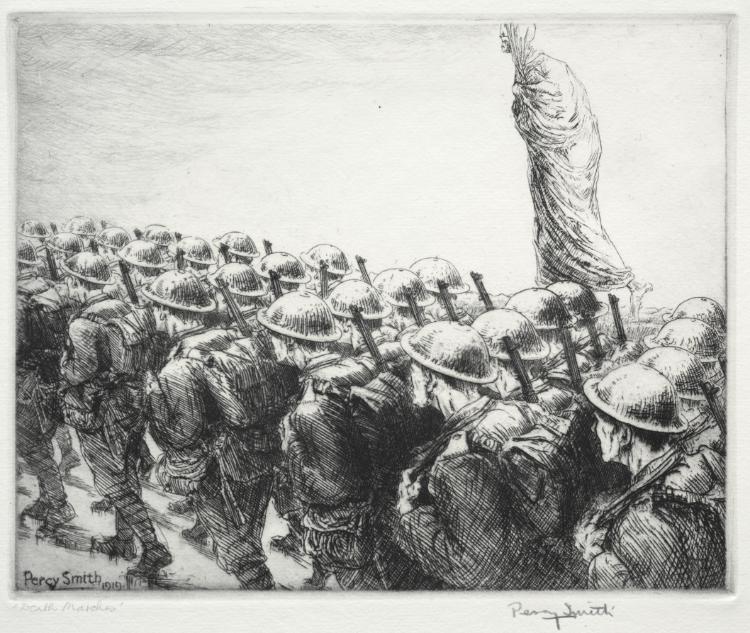

The tread of troops  Dance of Death: Death Marches, 1919, by Percy John Delf Smith (1882–1948). Credit: Gift of The Print Club of Cleveland 1922.267.4/The Cleveland Museum of Art

Dance of Death: Death Marches, 1919, by Percy John Delf Smith (1882–1948). Credit: Gift of The Print Club of Cleveland 1922.267.4/The Cleveland Museum of Art

Not all marches are celebratory, of course. In simple yet persuasive detail, this piece transforms a military procession into a fated conveyor belt. The soldiers, numerous and yet finite, are faceless cogs in a war machine. Their destiny, it seems, will only satisfy the onlooker who watches from beyond, cloaked and skeletal.

Death Marches was one of seven instalments in a series. Each is as gruesomely grim as the next, with the personification of death seen lurking in the backdrop of war scenes. Percy John Delf Smith has been regularly praised for the work, which is both sympathetic to the plight of the fallen soldiers and horrifying in its callousness.

Steps of struggle  Christ Carrying the Cross by Martin Schongauer (c.1450–91), c.1475–90. Credit: Dudley P Allen Fund 1941.389/The Cleveland Museum of Art

Christ Carrying the Cross by Martin Schongauer (c.1450–91), c.1475–90. Credit: Dudley P Allen Fund 1941.389/The Cleveland Museum of Art

Perhaps the most commonly represented march of all, a version of this scene of Jesus and the cross can be found engraved, painted, stained or otherwise portrayed in countless locations around the globe.

This particular version from Germany – a complex engraving rich with detail – has all the familiar ingredients. Jesus, crowned with thorns, is struggling to reach Golgotha, where he shall be crucified on the large cross that drags him down.

Here Jesus looks beyond the artwork to the viewer, his pain clearly visible. All others are ignorant of observation, fixated as they are on the man in front of them. It is the fierceness of this struggle that makes the piece so effective, and Martin Schongauer – one of the most influential European graphic artists of his time – was likely looking to use it as a way of cementing the religious beliefs of those who saw it.

Rank and file  Troops on the March, by Jean-Baptiste Joseph Pater (1695–1736), c.1725. Credit: Bequest of Ethel Tod Humphrys, 1956/The Met Collection

Troops on the March, by Jean-Baptiste Joseph Pater (1695–1736), c.1725. Credit: Bequest of Ethel Tod Humphrys, 1956/The Met Collection

Born in the aftermath of the wars of Louis XIV, the artist Jean-Baptiste Joseph Pater was as shaped by the historical context of his surroundings as he was the mentorship of Jean-Antoine Watteau. Pater grew up in Valenciennes, which had only recently been restored to France having previously been held as part of the Spanish Netherlands.

This idea of shifting sands and people being moved in and out is clear here in this oil painting. There are marchers, armed with weapons, and there are followers who must keep up: children and pets among them.

The son of a sculptor, Pater built a name as an artist of military scenes before moving onto landscapes and themes that revolved less around the violence of his early years.

About the Author

Ciaran Sneddon

Writes for The Arts Society

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition