This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

‘You start to forget that you are naked’: the shock of the nude, with Stella Lyons

‘You start to forget that you are naked’: the shock of the nude, with Stella Lyons

25 Oct 2018

For millennia, artists have used the naked human form to titillate, to scandalise, to worship and to revolutionise. For centuries, art historians have battled over this most intimate and political of artistic subjects; few subjects in art history are more contentious than ‘the nude’.

As the Laing Art Gallery’s new exhibition, Exposed: The Naked Portrait, poses the questions afresh, we sit down with Arts Society Lecturer and life model Stella Lyons, to discuss whether the nude can still shock – and what it’s like to strip off in the artist’s studio.

Art historian Stella Lyons

To you, what is the difference between a ‘nude’ and a ‘naked portrait’ – as the Laing has categorised the works in its exhibition?

This distinction between ‘nude’ and ‘naked’ is something art historians have been arguing about for years. Kenneth Clark famously attempted to define both terms in his seminal 1956 book, The Nude. His argument was that ‘naked’ was a person without clothes, but that a ‘nude’ was ‘a form of art’. To him, the nude body was classically posed, idealised and perfected; Titian’s Venus of Urbino, or the beautiful, contorted bodies of Ingres’s odalisques. ‘Naked’, in art historical terms, brings to mind a more realistic and less idealised body; something exposed, vulnerable and flawed. For example, Manet’s scandalous Olympia, Egon Schiele’s bodies, Freud’s defenceless portraits, or Jenny Saville’s graphic paintings.

But is there really a difference? I’m not sure there is. I think the term ‘nude’ has been distinguished from ‘naked’ as a way of making the body artistically acceptable and academic. It’s often been used to help justify paintings that are, in reality, very similar to soft porn; simply designed to titillate.

Nell Gwyn attributed to Simon Verelst, c 1670 Ⓒ National Portrait Gallery, London

Is the nude always an object of desire? Is the sexuality of the artist always implicit in the artwork?

So many of the nudes in the history of art are objects of desire. Particularly female nudes. John Berger said in Ways of Seeing in 1972 that ‘men act and women appear’. I think a vast percentage of nudes conform to this idea: the female nude as passive and the male as active.

There are, however, artists who have challenged this idea throughout art history and disrupted the status quo. In the late 19th century, there was an explosion of works showing dangerous, femme fatale nudes. Images of Salome with the head of John the Baptist were particularly popular. These can certainly be termed ‘active’ female nudes. In the 1970s, a female artist called Sylvia Sleigh painted her husband nude in feminine, reclining, ‘passive’ poses. She was challenging the idea of the ‘male gaze’, and instead presenting us with a woman as ‘artist-genius’, and a male as an ‘object of desire’. Although the images aren’t particularly confrontational, I was still censored from showing one of these paintings in a lecture recently!

![]()

Mick Jagger; Jerry Hall by Norman Parkinson, Jul 81 © Norman Parkinson Iconic Images

Can a nude be both erotic and ideal?

Yes, absolutely. In the history of art, most eroticised images of female nudes are also idealised. They are presented in a mythological context, as goddesses, or ‘other’; detached from reality, and therefore perfectly acceptable for educated minds to look at. An example is the French artist Cabanel’s Birth of Venus. She is extremely idealised; a goddess with porcelain smooth skin and beautiful curves. She turns her head away from the viewer, so that her beauty can be gazed upon in a non-challenging or non-confrontational atmosphere. Most of the buyers and viewers for these works were male.

A more recent example would be the fetishised works of Allen Jones. His women have exaggerated body parts, straight out of a comic book, and are wearing bondage clothing. These are fantasy women, sculptures moulded into sexual poses and turned into objects; he made a whole series of sculptures that were also practical pieces of furniture, such as chairs or tables. Most of the problematic nudes in art history have been problematic precisely because they aren’t idealised. One reason critics despised Manet’s Olympia was because she didn’t conform to 19th-century standards of beauty, and she certainly wasn’t a goddess. Audiences didn’t find her erotic in the slightest.

Stella Looking at Munch's Madonna

Has the nude lost its ability to be subversive?

Not at all. I think the nude is now one of the most subversive and controversial genres in art. Today we are censoring images of the body at an increasingly alarming rate. In the age of #MeToo we are also questioning what is and isn’t appropriate to hang on the gallery wall. Only this year Manchester Art Gallery made the daring decision to remove Waterhouse’s Hylas and the Nymphs. In my opinion, this was insanity. If you want to start a debate about the nude, why remove the subject of the discussion? Secondly, of all the paintings to remove, this one seemed a strange choice. The painting illustrates a classical myth; the nudity is far less obvious and extreme than many other Victorian works, such as Alma-Tadema’s In the Tepidarium. Thirdly, the whole stunt was undermined by the fact that a female, Victorian artist Henrietta Rae, had painted the exact same subject even more erotically than Waterhouse. Had Manchester owned that painting, would they have removed it? Somehow, I think not. We call the Victorians prudish, but I think we are far more prudish than they ever were. And much more concerned with making the nude politically correct.

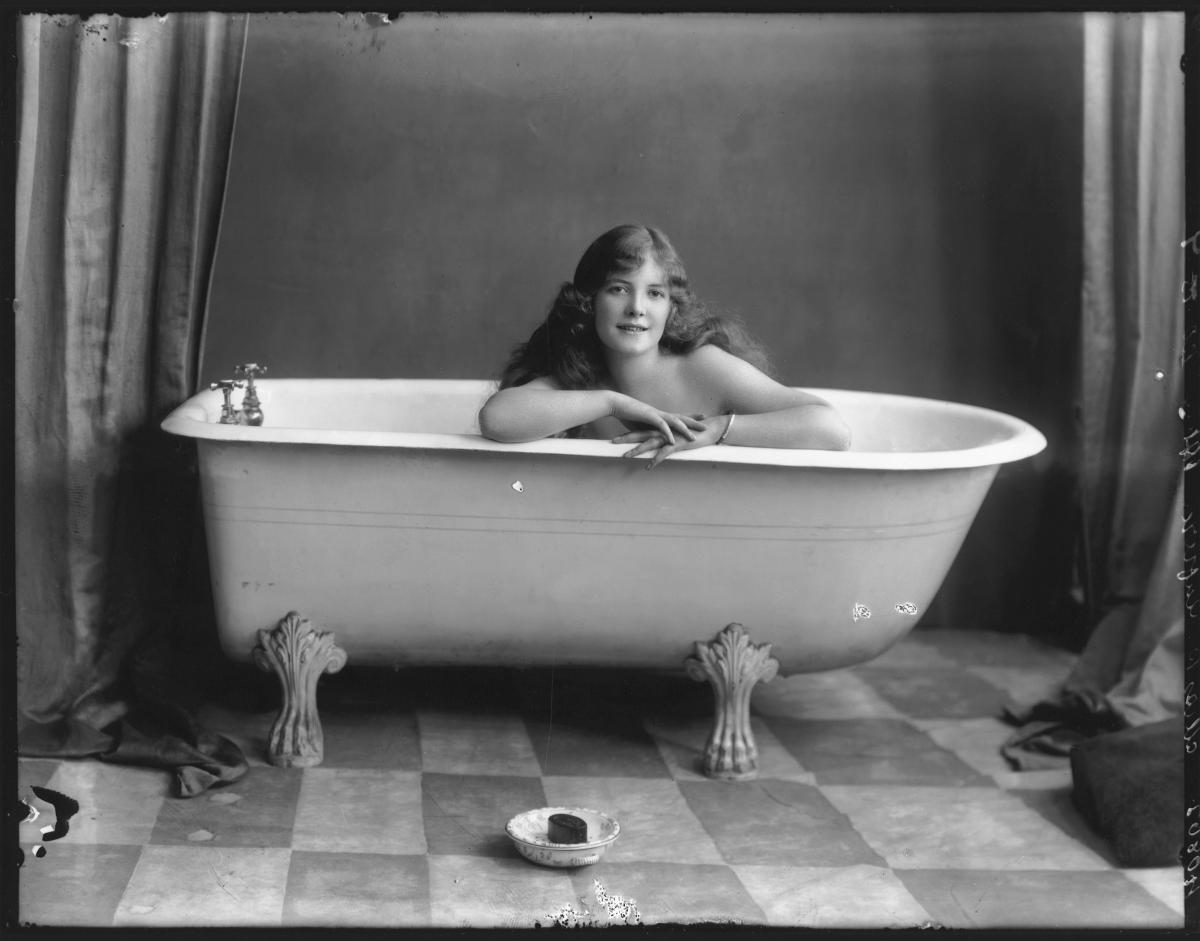

Pearl Aufrere, Bassano Ltd, 2011 © National Portrait Gallery, London

Do you think that the cultural climate has changed since 1989, when the Guerrilla Girls asked Do Women Have To Be Naked To Get Into the Met. Museum?

It’s changed, but probably not enough. There is certainly more awareness of women artists. Galleries are making a concerted effort to hang more works by female artists, and to include more works in exhibitions. There is still a long way to go, and I suspect it will take a while before female artists are appreciated in the same way that male artists are.

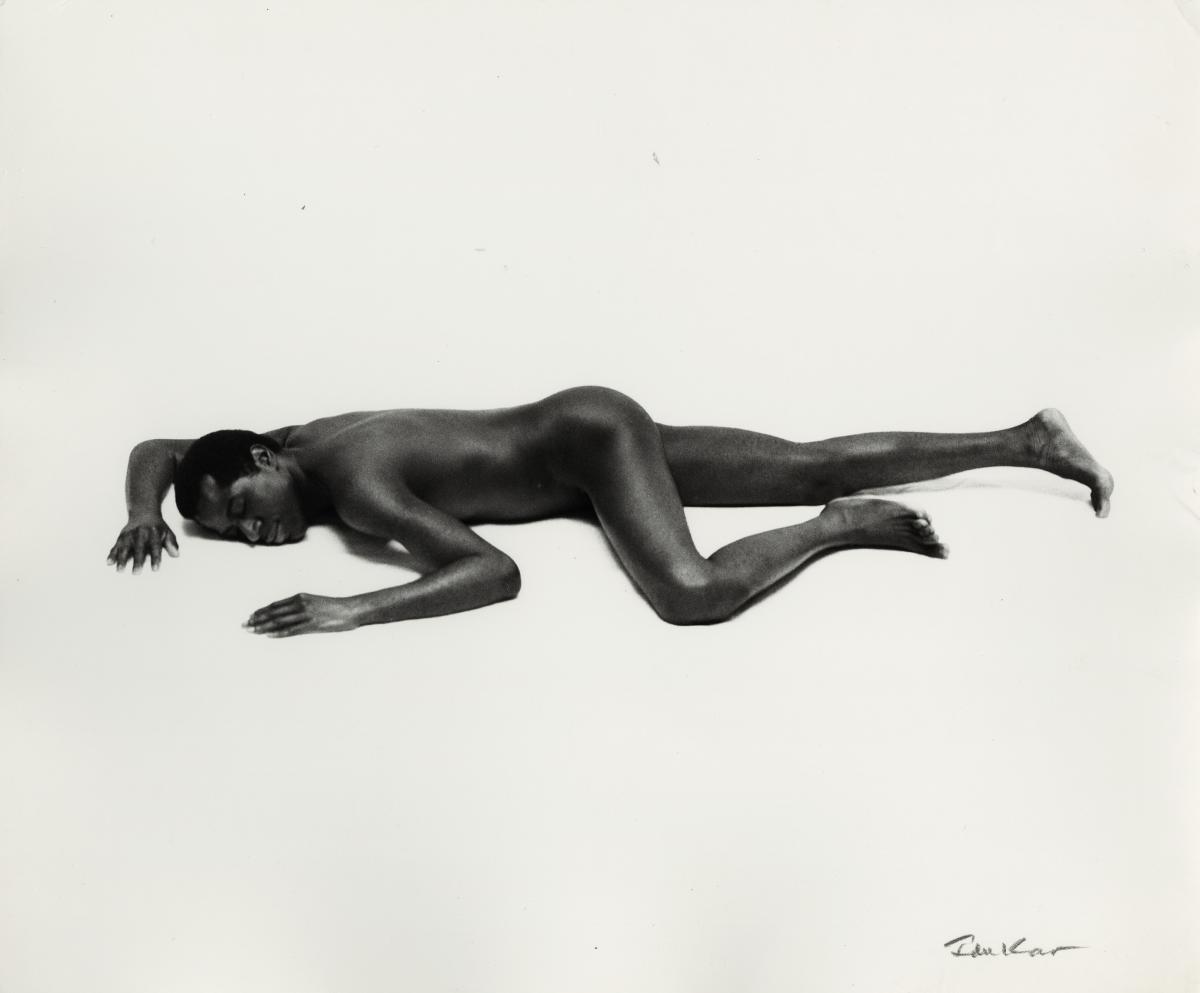

Anthony Sobers, Ida Kar, 1974 © National Portrait Gallery, London

Can you tell us a little about the life modelling that you do? What does it feel like to be in that room?

I've been modelling for the artist Harry Holland since I was 23; I'm now 29. The first time I did it, it felt incredibly exposing. But once you get used to it, it’s actually more mundane than you could imagine. You start to forget that you’re naked and end up thinking about what you’re going to cook for dinner! Harry puts on some jazz music, and over the course of two hours I'll probably do about three poses. It’s either relaxing or, if it’s a difficult pose, it’s rather painful, and you have to concentrate on keeping your muscles still.

I think if you are a life model, you have to accept that you are going to be viewed as an object. You are just a mass of volumes that the artist is painting. It might be problematic for some feminists; you're stripping off in front of an artist who is viewing you as purely an object. But, for me, it's much more removed than that. I end up thinking about the history of art and the countless models that have gone before me. And the relationship between Harry and I – well, he's 77. It's a very intimate friendship that we've fallen into; he sees me in my most vulnerable state. I always look forward to our break-time chats over a cup of tea!

Eventually, I will stop. But for now, I really enjoy it, and I find it helpful for my lecturing work, as well as my technical knowledge of art.

Academic, art historian and Arts Society Lecturer Stella Lyons is working on a book about the nude, and the relationship between artist and model. She also works as an artist’s model for figurative artist Harry Holland. Find out more about Stella by visiting stellagracelyons.com

About the Author

The Arts Society

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition