This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

Five Scottish artworks for St Andrew’s Day!

Five Scottish artworks for St Andrew’s Day!

30 Nov 2023

To mark this big day in Scotland’s calendar, here are works by five of the artists who loom large in the story of Scottish art

Remember, remember the 30th of November. For this is the night, and day, of Andrew the Apostle, patron saint of Scotland. He’s also the patron of Cyprus, Greece, Romania, Russia, Ukraine and several other territories, although only Scotland officially treats 30 November as a day of celebration.

A bank holiday since 2006 – although one that requires neither banks nor schools to close – it is, perhaps, second only to Burns Night in the Scotland-only calendar of events. What an opportunity, then, to explore some of the greats in Scotland’s art scene, past and present.

Swoops and curves

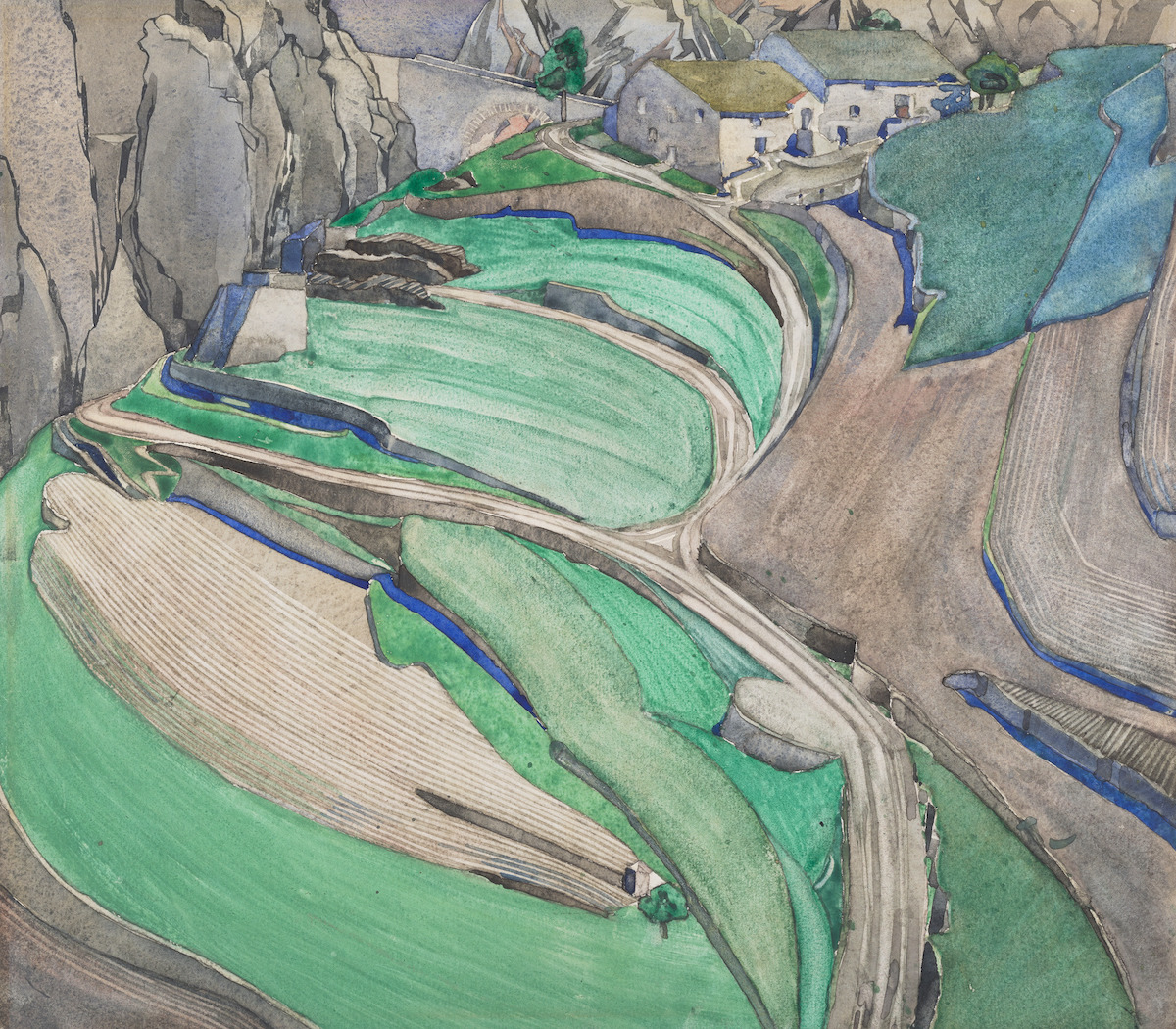

Mont Alba by Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1868–1928), c.1924–27. Image: Scottish National Gallery, purchased 1990

Mont Alba by Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1868–1928), c.1924–27. Image: Scottish National Gallery, purchased 1990

Arguably, we would be as well highlighting any one of the buildings that Charles Rennie Mackintosh designed as we are to profile only one artwork, for all of them are hugely influential.

Sadly, though, two of the most prominent examples of Mackintosh’s architecture are not visible at present. Hill House in Helensburgh is currently housed behind a defensive mesh (called the Box) while the National Trust for Scotland finds a solution to the property’s saturated walls and crumbling exteriors. The Glasgow School of Art, meanwhile, was famously damaged by a fire in 2014. Shortly before restorations were due to be completed in 2018, a second fire caused catastrophic damage to even more of the building.

We think, though, that while watercolours such as this may only form a small part of Mackintosh’s overall portfolio, they are generally uncelebrated. Having moved to France in 1923 with his wife, Mackintosh painted dozens of such landscapes that share some swooping and undulating similarities with his other work, while offering a fresh medium for the famed artist. This beautiful work sits in the collection of the Scottish National Gallery.

Truly equal

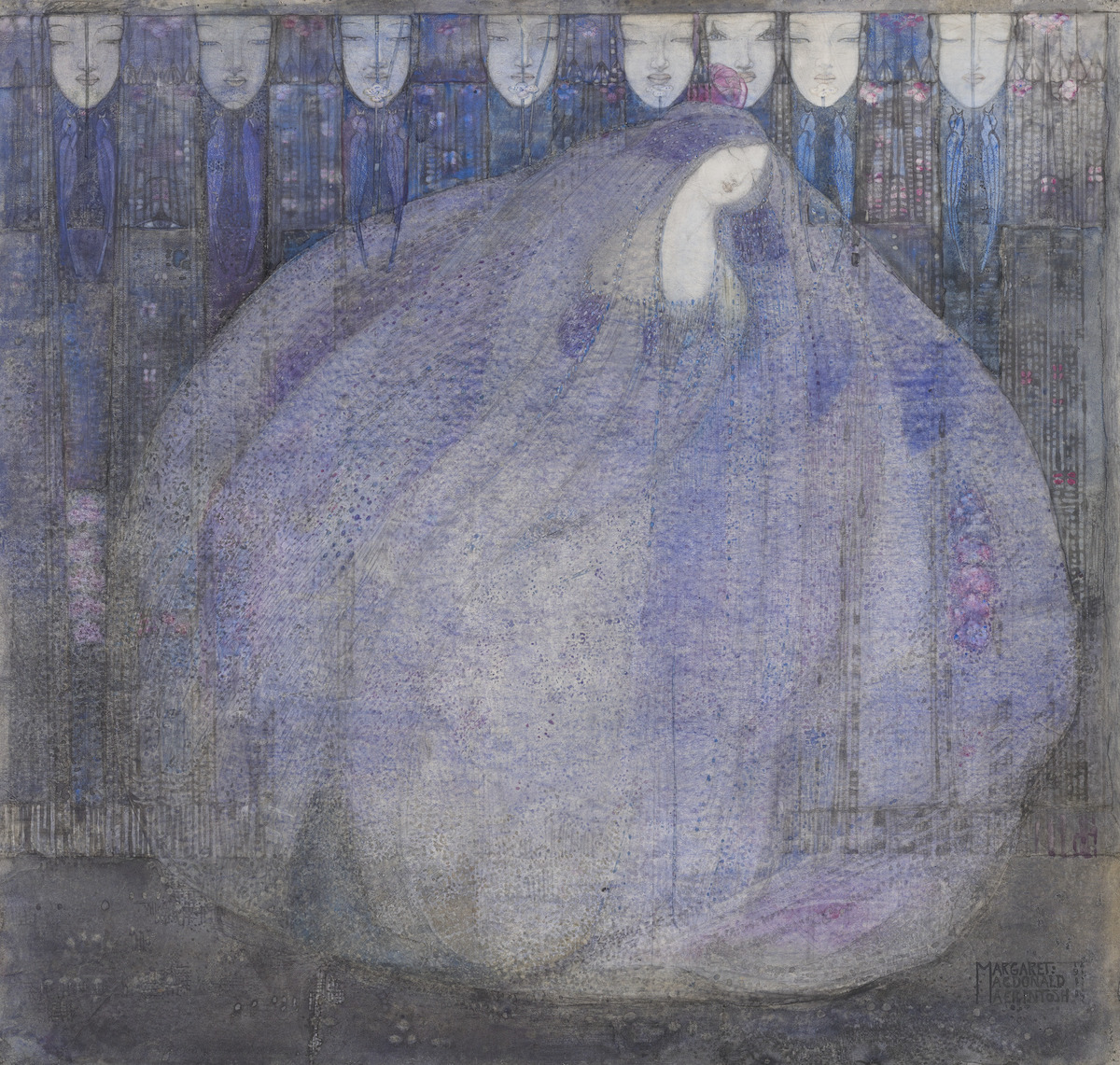

The Mysterious Garden by Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh (1864–1933), 1890. Image: Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh, purchased with Art Fund support, 2011

The Mysterious Garden by Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh (1864–1933), 1890. Image: Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh, purchased with Art Fund support, 2011

While often overshadowed by the insurmountable legacy of her husband, Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh’s own contribution to Scotland’s cultural catalogue is no less impressive. Although English born, she came to define the Glasgow style of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, known mostly for her glasswork, metalwork and embroidery.

Her husband credited her as ‘half if not three-quarters’ of his architectural work and as a person of genius compared to him, a person of ‘only talent’. Like her husband, Mackintosh also turned her hand to watercolours and this piece is possibly inspired by a play, The Blue Bird, which had been performed in Glasgow the year prior to its creation.

Ethereal and dreamlike, it was one of a small collection of watercolours displayed by Mackintosh in 1912. She stopped producing work in 1921 and died a little more than four years after her husband.

Gliding by

Reverend Robert Walker Skating on Duddingston Loch by Sir Henry Raeburn (1756–1823), c.1795. Image: Scottish National Gallery, purchased 1949

Reverend Robert Walker Skating on Duddingston Loch by Sir Henry Raeburn (1756–1823), c.1795. Image: Scottish National Gallery, purchased 1949

Another leading light of Scottish art history, Sir Henry Raeburn is most celebrated for his portraits of Edinburgh’s elite. Ironically, it’s one of his more unusual paintings that has become his most iconic. This, of a skating minister, was kept in the artist’s family until 1949 but has since become one of the nation’s best-known artworks.

While not quite on the level of Torvill and/or Dean, the competent skating of Edinburgh Skating Society member Reverend Robert Walker was immortalised by his artist friend. It’s an admiring rendition of the skater, given his relative poise and seemingly effortless attempt at performing a tricky glide.

Curiously, because the painting was passed down through the generations of Raeburn’s descendants, there is no historical record of it – nor is it contained in any early books on Raeburn’s work. However, its unique qualities, contrasted with the typically stoic and staged offerings of other Edinburgh citizens, lends it a certain prominence.

Feisty gaze

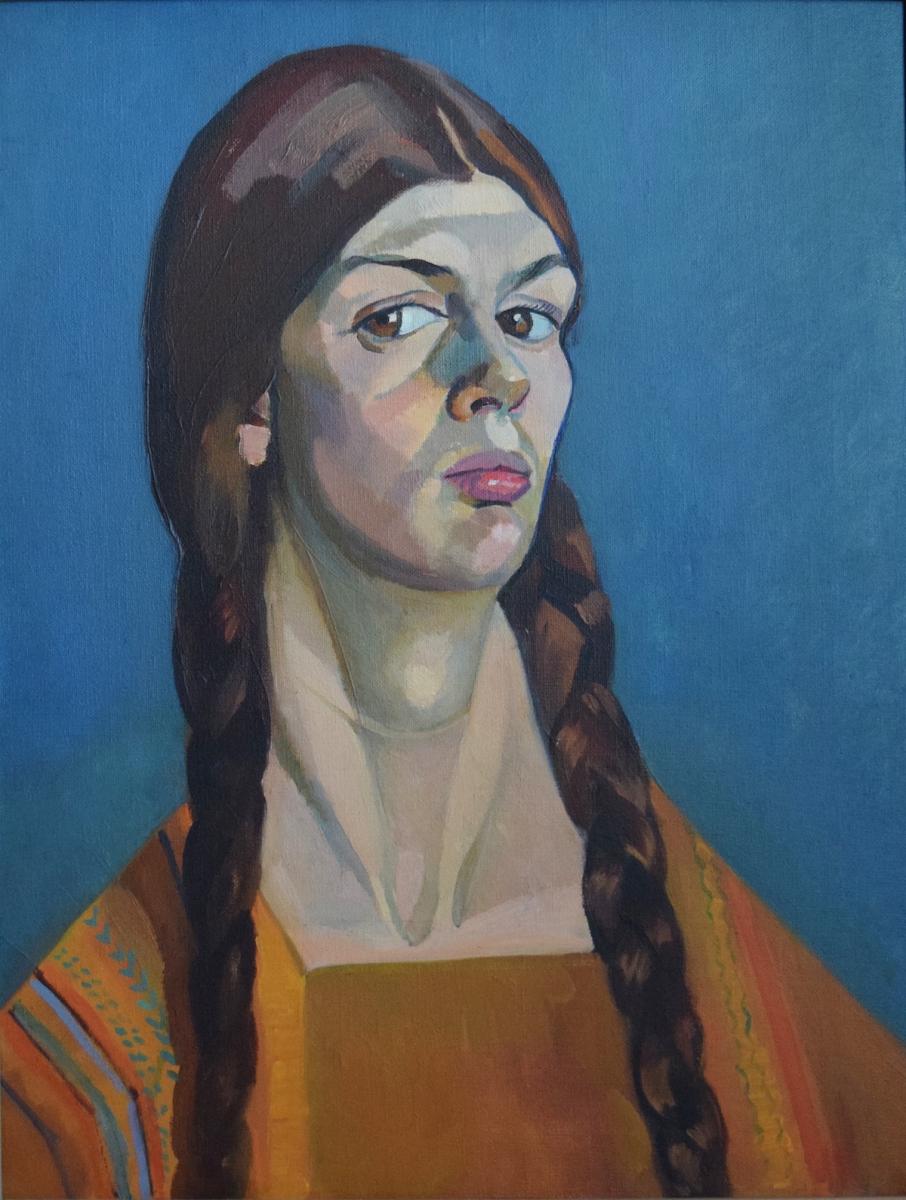

A Cellist, by Beatrice Huntington, c.1925. Image: The Fleming Collection © The William Dyson Foundation

A Cellist, by Beatrice Huntington, c.1925. Image: The Fleming Collection © The William Dyson Foundation

Painted in 1925, we love this work by cellist and artist Beatrice M L Huntington (1889–1988). Huntington’s career was long and she became known for her intuitive portraits, which didn’t shy from a bold use of colour, particularly later in her career when she was influenced by Modernism. Much like Charles and Margaret Mackintosh, Huntington also had a strong artistic partnership with her husband, the painter William Macdonald.

This work features in an important show of works by female artists whose actions and art, over 250 years, have shaped Scotland’s art scene today. Entitled Scottish Women Artists: 250 Years of Challenging Perception, it runs at Dovecot Studios in Edinburgh until 6 January. Works include those by the Glasgow Girls, Elizabeth Blackadder, Joan Eardley and Wilhelmina Barns-Graham. It also features groundbreaking art by current artists, among them Alberta Whittle and Rachel Maclean (see below).

Tactile art

I’m Fine / Save Mi by Rachel Maclean (1987–present) and Dovecot Studios 2021. Image: Kenneth Gray

We remain at the Dovecot exhibition for this textile artwork designed by Rachel Maclean, whose art disguises the macabre under bright colours and seemingly cartoonish characters.

The Glasgow-based creator has dabbled with many media, including film, photography, technology and tapestry. These two rugs – made by Dovecot weavers and tufters Louise Trotter and Ben Hymers based on Maclean’s designs – are a representation of body dysmorphia.

At the centre is a regular character of Maclean’s called Mimi surrounded by reversible figures that highlight the sense of having flaws that cannot be unseen once noticed. Text that reads ‘I’m Fine’ or ‘Save Mi’, depending on the way in which it is seen, add to the curious, arresting effect.

About the Author

Ciaran Sneddon

writes for The Arts Society

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition