This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

8 things we’ve discovered about the story of shells, artists and collectors

8 things we’ve discovered about the story of shells, artists and collectors

7 Sep 2022

The colourful freshwater zigzag nerite shell. Photo from the book Interesting Shells

The colourful freshwater zigzag nerite shell. Photo from the book Interesting Shells

Andreia Salvador, curator at the Natural History Museum, London, reveals fascinating facts linking shells to the world of art and collecting

1. The colours, patterns and shapes of shells have long mesmerised collectors. By the beginning of the 17th century, shells were being proudly displayed alongside precious works of art and antiques in cabinets of curiosities. The artist Rembrandt had a marbled cone in his collection, which he etched in his 1650 work The Shell, a whole century before that shell was officially described by Carl Linnaeus.

The glassy nautilus shell. Photo from the book Interesting Shells

The glassy nautilus shell. Photo from the book Interesting Shells

2. When the Dutch artist and naturalist Pièrre Lyonet died in 1789 his collection was put up for sale. Two years later a Johannes Vermeer painting from that collection, Woman in Blue Reading a Letter,

was sold for 43 guilders. Five years on, another object from Lyonet’s treasure trove was sold for seven times that price (299 guilders). That piece was the translucent shell of a glassy nautilus.

3. A prime example of a collection that contained shells comes with that of Sir Hans Sloane, the Irish physician and scientist. He acquired some 71,000 items in all, which became the foundation of the British Museum collection. In part due to a far-reaching network of traders, apothecaries, physicians, naturalists and collectors, Sloane was supplied with plants, animals, antiquities, coins, books, drawings and maps, as well as exquisite antiques and curiosities from across the globe. Among those treasures were some 6,000 shells.

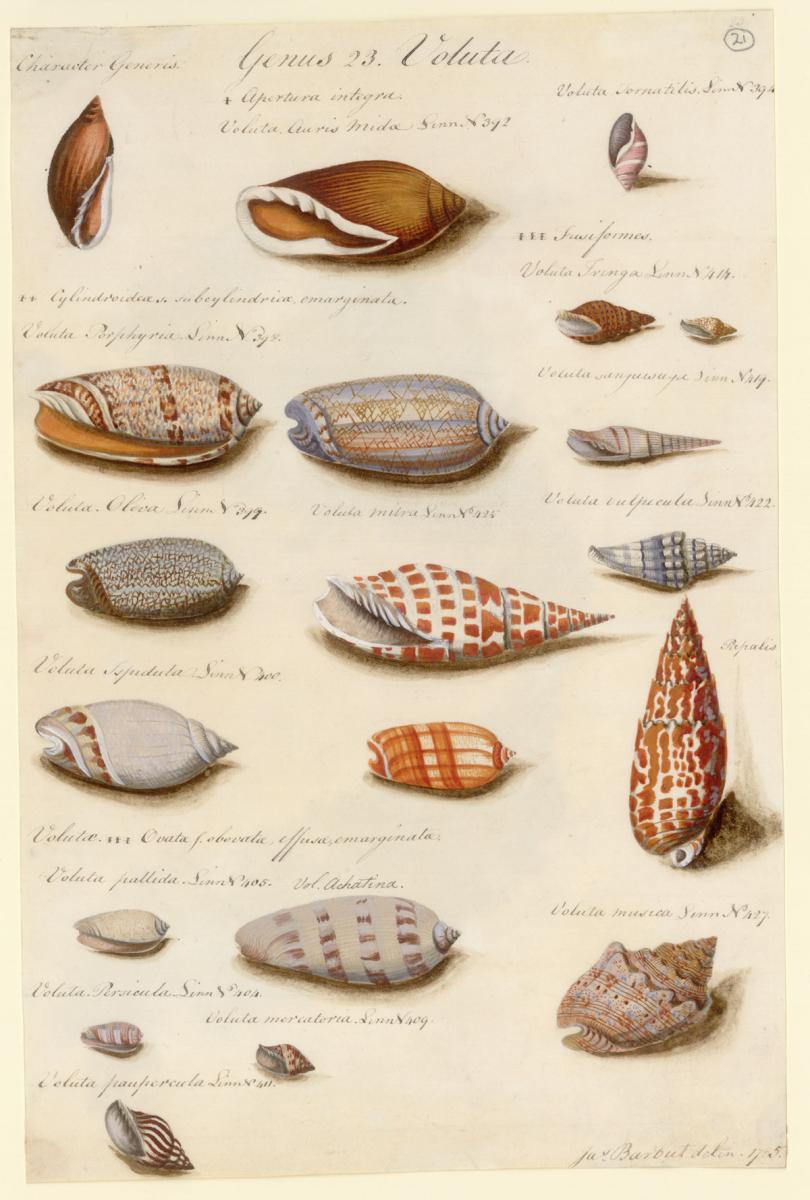

Shells by naturalist James Barbut, who was active from 1776–91. © The Trustees of the Natural History Museum, London

Shells by naturalist James Barbut, who was active from 1776–91. © The Trustees of the Natural History Museum, London

4. The 18th century was to see a shell-collecting frenzy take hold of European collectors. The Dutch East India Company played a major role in this. It dominated the market in imported spices and other products, and it was also bringing exotic shells to European shores for the private museums of wealthy collectors. The trend became known as ‘conchylomania’, from the Latin concha for shell; it was a name inspired by ‘tulipmania’, the 17th-century Dutch passion for collecting tulip bulbs.

The precious wentletrap. Photo from the book Interesting Shells

The precious wentletrap. Photo from the book Interesting Shells

5. Some shells were in such demand that, at the height of conchylomania, they were counterfeited. Shells such as the exquisite precious wentletrap, a marine snail from the Indo-Pacific, were cleverly and audaciously replicated using rice flour. It is said that the fraudulent shells were eventually detected by the owners who dipped them into water to clean them, only to watch their ‘valuable’ new purchases become worthless blobs.

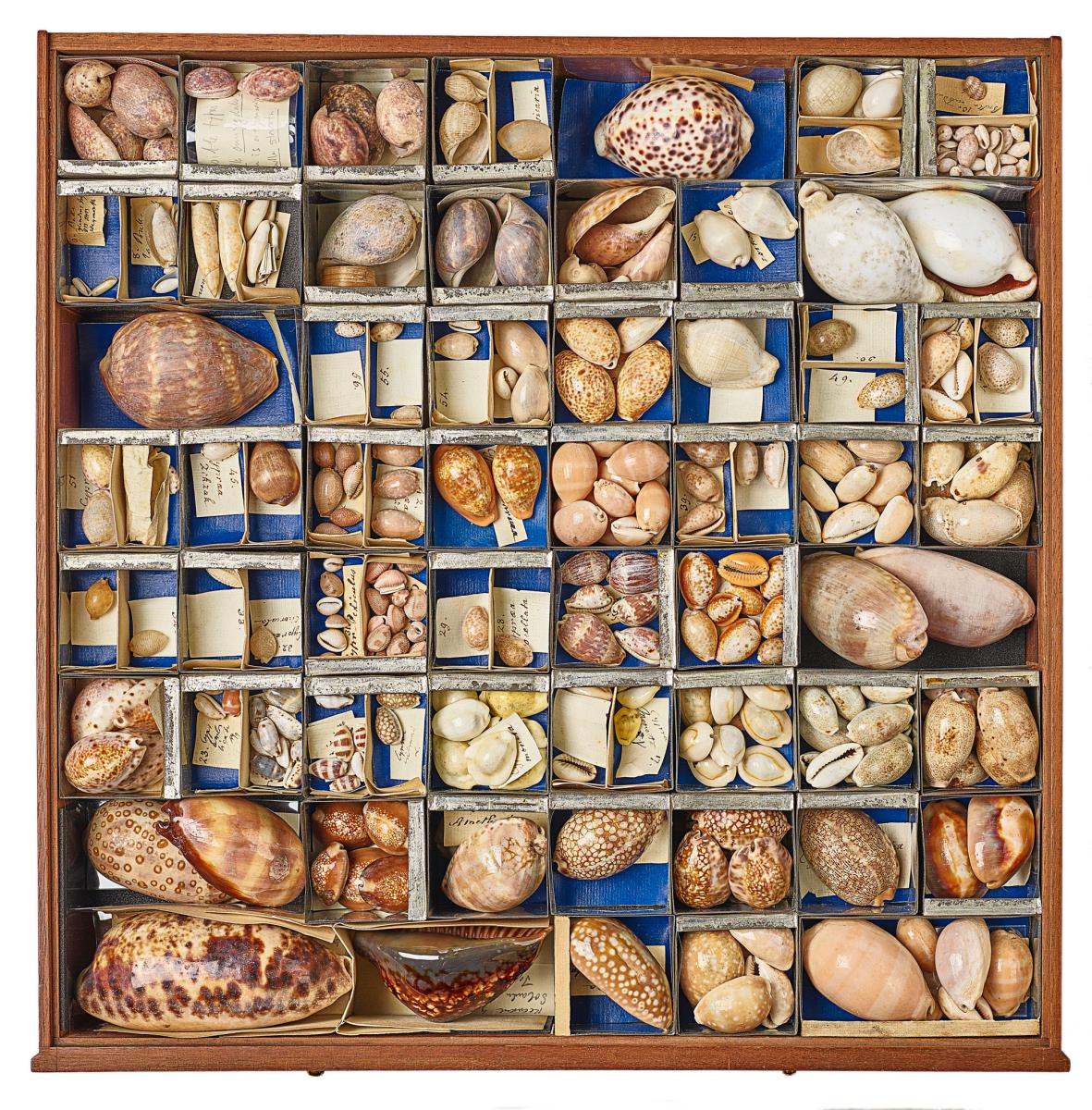

Shells collected by Joseph Banks during the HMS Endeavour expedition 1768–71. © The Trustees of the Natural History Museum, London

Shells collected by Joseph Banks during the HMS Endeavour expedition 1768–71. © The Trustees of the Natural History Museum, London

6. Joseph Banks, the scientist on board Captain Cook’s first famous voyage, was a botanist who extensively collected plants throughout the voyage – and he could not resist collecting shells. The majority of Banks’s shell collection is still housed at the Natural History Museum and there is a particular fact attached to them: all the surviving Banks shells are small and pocket-sized. They were just the right size to, literally, pop in his pocket when scouring the shores.

The glory of the sea. Photo from the book Interesting Shells

The glory of the sea. Photo from the book Interesting Shells

7. At the peak of the collecting frenzy, some shells became legendary as they were rare and harder to glean. The most fabled of all was the handsome Conus gloriamaris, ‘the glory of the sea’, a marine cone snail that lives in the Indo-Pacific. It was, until the mid-20th century, considered the rarest, most coveted and costliest shell in the world. It inspired the central theme of the book The Glory of the Sea (1887) by Victorian novelist Francesca M Steele, and it is the only shell known to have been stolen from a museum gallery – the American Museum of Natural History, in 1951. In 1964 a fine specimen was sold for $2,000, a record price for the species.

8. The last of the famed examples is naturally the glassy nautilus. This shell is extremely thin, fragile and translucent, as if made from the finest spun glass. It was thought to be the shell of a small nautilus, hence its vernacular name, but is in fact the shell of a heteropod or sea elephant, a snail that lives in the open sea. The mystery surrounding this curious animal and the scarce opportunity to acquire an unbroken shell of this species were almost certainly the reasons why Lyonet’s shell would fetch so much money in 1796.

Find out more

Read the full feature in the summer issue of The Arts Society Magazine, available exclusively to Members and Supporters of The Arts Society (to join, see theartssociety.org/member-benefits)

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition