This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

Understand these Surrealist symbols

Understand these Surrealist symbols

18 Feb 2022

There are hidden meanings found in artists’ dreamlike images – here are a few you should know

The key principle of Surrealism, as laid out in André Breton’s 1924 manifesto, is to do away with rationalism in favour of the vast unknown of our subconscious, not to mention harnessing the significant power of our dreams. What might seem like an incomprehensible scene is full of coded imagery. Here are a few of our must-know examples, which feature in a new expansive exhibition, Surrealism Beyond Borders, at Tate Modern.

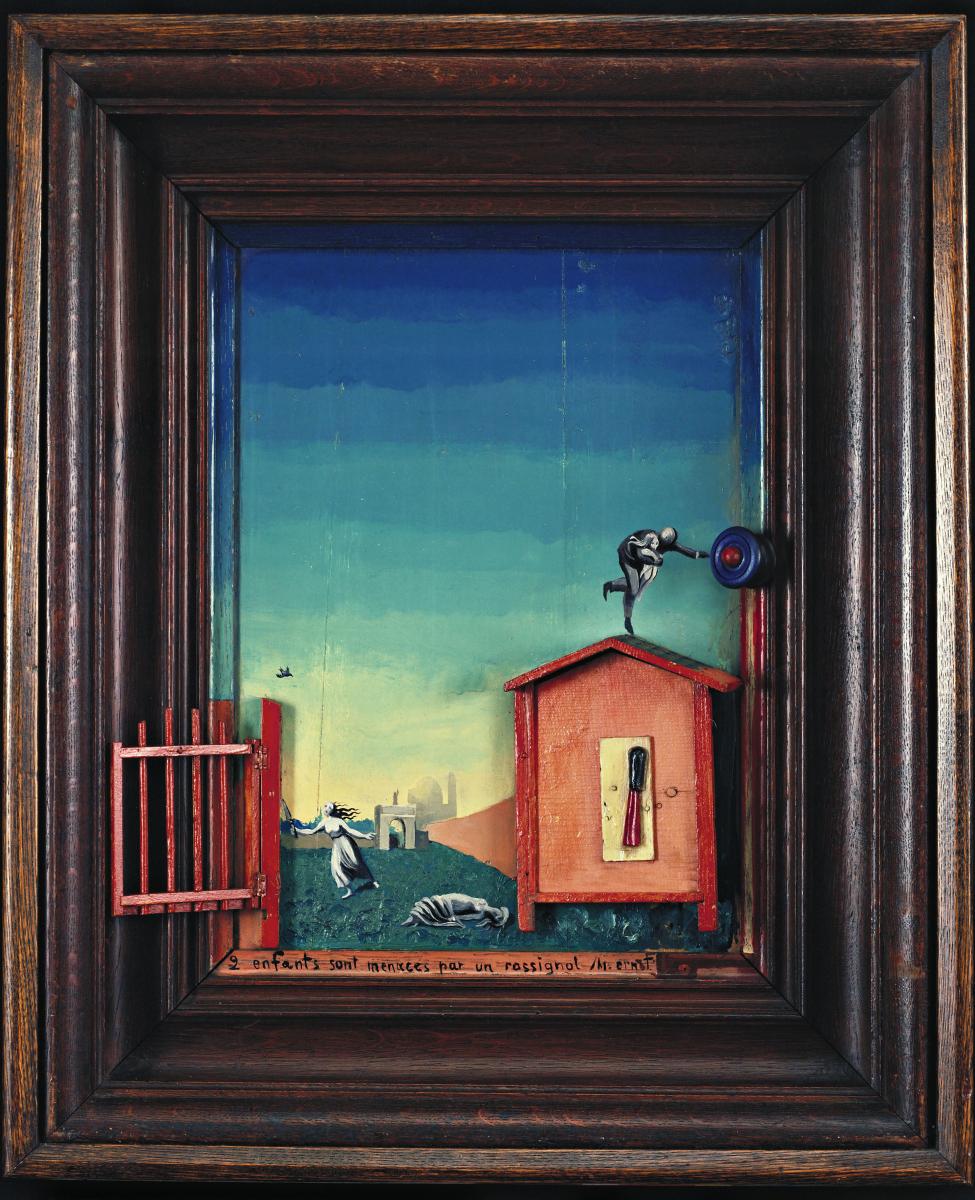

Max Ernst, Two Children Are Threatened by a Nightingale, 1924. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Purchase (256.1937) © 2022 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

Birds

The bird has long been viewed as a metaphor for the soul, which might appear caged or flying free. For Max Ernst, however, the animal had a dual meaning. Having supposedly seen his pet parrot die at the exact moment his sister was born, avian species recur as not only representations of the self, but as the inescapable shadow of death. They might appear as erotic and nightmarish figures, as seen in The Barbarians (1937), or as a distant threat, as seen in Two Children Are Threatened by a Nightingale (1924).

Toshiko Okanoue, The Call, 1953. Wilson Centre for Photography © Okanoue Toshiko, Courtesy of The Third Gallery Aya

The sea

While plenty of Surrealists looked to dreams for their inspiration, Eileen Agar looked to the sea. She combed the beaches for flotsam and jetsam that could be used in her strange assemblages, and continually depicted the vast bodies of water as a way of considering the vast unknowability of human nature. In the work of Toshiko Okanoue, who was embraced by the Japanese Surrealist movement thanks to her deft photomontages, the sea played a similar role, as a seemingly untameable force. The Call (1953), for example, sees a glamorous Western woman trapped within the confines of her luxurious abode, while the waves (and a snarling wolf head) rage on.

Leonora Carrington, Self-portrait, c.1937–38. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Pierre and Maria-Gaetana Matisse Collection, 2002 © 2022 Estate of Leonora Carrington / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Image © Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Windows

These physical and metaphorical portals appear as allusions to another state of consciousness, or perhaps highlight the entrapment and turmoil the artist endures while being teased by the world beyond. In terms of the former, René Magritte continually returned to the idea, employing optical illusions to baffle and intrigue his audiences. Meanwhile, Leonora Carrington’s Self-Portrait (1937–8) is a perfect example of internal struggle. She is depicted sitting wild-haired and wearing jodhpurs in a sterile room, while she witnesses her true spirit – which was often represented in equine form – roaming free.

Salvador Dalí Lobster, Telephone, 1938. Tate Purchased 1981 © Salvador Dali, Gala-Salvador Dali Foundation/DACS, London 2022

Lobsters

Salvador Dalí’s Lobster Telephone (1938) is perhaps one of the best-known Surrealist works. While the sculpture is patently absurd, the lobster represented sexuality and eroticism for the artist. They also appear in sexually charged drawings, and again in his project Dream of Venus (1939), which involved nude women wearing costumes encrusted with crustacea, and positioned in rather intimate places.

René Magritte, Time Transfixed, 1938. The Art Institute of Chicago, Joseph Winterbotham Collection, 1970.426 © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2022

Clocks

Time is too linear a concept for the Surrealist mindset, and yet clocks can be found everywhere. They melt in desert landscapes in Dalí’s most experimental paintings and appear as markers of logic and the futility of onward progression in works such as Magritte’s Time Transfixed (1938), which features a seemingly mundane and realistically depicted room cut through by the presence of a tiny steam train coming out of the fireplace. Magritte was not a fan of the title’s English translation, preferring the original La durée poignardée, literally meaning ‘ongoing time stabbed by a dagger’. The notion of the fabric of space and time being torn asunder is certainly clear here.

SEE

Surrealism Beyond Borders at Tate Modern, London

24 February–29 August 2022

tate.org.uk

About the Author

Holly Black

Holly Black is The Arts Society's Digital Editor

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition