This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

Become an Instant Expert on the Art of Topiary

Become an Instant Expert on the Art of Topiary

10 Aug 2021

Leaping foxes, leafy peacocks, mazes and knot gardens – topiary is an art that has drawn gardeners for centuries. Our expert, Arts Society Lecturer Sophie Oosterwijk, takes up the tale

Verdant shapes – topiary at Great Dixter gardens in Sussex

‘Topiary goes through phases of being unfashionable, but it always bounces back’

The gardener Christopher Lloyd, of Great Dixter House and Gardens, in the preface to the 1995 edition of Nathaniel Lloyd’s Garden Craftsmanship in Yew and Box

1. EARLY CLIPPINGS...

Topiary has a venerable history.

In ancient Rome a ‘topiarius’ was an ‘ornamental gardener’. Pliny the Elder’s Natural History describes clipped hedges and shapes made from cypresses, boxwood and laurel. In a letter, his nephew, Pliny the Younger, mentions box-trees at his Tuscan villa, which were cut into different forms, along with clipped dwarf shrubs.

One particular form of topiary is the maze, usually made of yew. One such plays a crucial role in Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire. The concept, however, is much older than the tale of the young wizard and his adventures.

According to legend, Henry II (1133–89) hid his mistress, the ‘Fair Rosamund’, within a ‘mazy bower’ at Woodstock in Oxfordshire. Other topiary mazes recorded include the one in the grounds at Hampton Court, its precise origins uncertain, but thought to have been commissioned in the 17th century. And an early painting in the Royal Collection – Pleasure Garden with a Maze – by the Flemish landscapist Lodewijk Toeput (c.1550–c.1603/5) shows a fantastical topiary maze set within a pleasure garden.

The golden age of topiary was the 16th and early 17th century. In his 1540 Itinerary the poet and antiquary John Leland colourfully describes how, at Wrexhill Castle in Yorkshire, there was ‘opere topiorii, writhen about with degrees like the turnings in cokil shelles’. Formal topiary knot gardens with aromatic plants and herbs also became popular during Elizabeth I’s reign, their undulating low hedges looking as if they had, indeed, been interwoven into knots.

Some clipped yews and monumental hedges created from this time survived for centuries, even if they gradually outgrew their original form. Quirky shapes were also fashionable. The pastoral poet Barnabe Googe (1540–94) describes women trimming rosemary in the form of carts, peacocks and any other shapes they fancied.

Crisp elegance: the gardens at Het Loo

2. HIGH TASTE AND LOW ESTEEM

Tastes, however, do change.

In his 1625 essay Of Gardens the philosopher, scientific thinker and statesman Sir Francis Bacon expressed disdain for ‘images cut out in juniper or other garden stuff: they be for children’.

Yet Bacon approved of some forms of topiary. ‘Little low hedges, round, like welts, with some pretty pyramids, I like well,’ he wrote. In doing so he anticipated the Baroque parterre gardens at Versailles, created for Louis XIV in the second half of the 17th century, or those at one of William and Mary’s Dutch palaces, Het Loo in Apeldoorn. There, low evergreen hedges, or ‘broderies’, were combined with geometric topiary shapes, such as balls and obelisks.

With the introduction of the Dutch formal garden in England, a fanaticism for clipped greens and geometry developed. From 1689 the famous landscapers and partners at Brompton Park Nursery, George London and Henry Wise, specialised in Anglo-Dutch gardens with box hedges, elaborate waterworks, canals and radiating avenues of trees.

Inevitably, these geometric patterns fell out of favour, along with the ‘curious shapes’ that some old-fashioned gardeners still delighted in. By the time the park and famous topiary gardens of Levens Hall in Cumbria were finished in 1712, topiary had already begun to be derided as unnatural, vulgar and even an affront to good taste.

In the same year, the essayist Joseph Addison observed that British gardeners, ‘instead of humouring Nature, love to deviate from it as much as possible. Our Trees rise in Cones, Globes, and Pyramids. We see the Marks of the Scissars upon every Plant and Bush.’ Alexander Pope added to this in 1713, writing disdainfully: ‘A Citizen is no sooner proprietor of a couple of Yews, but he entertains thoughts of erecting them into Giants.’

Who would want topiary after that?

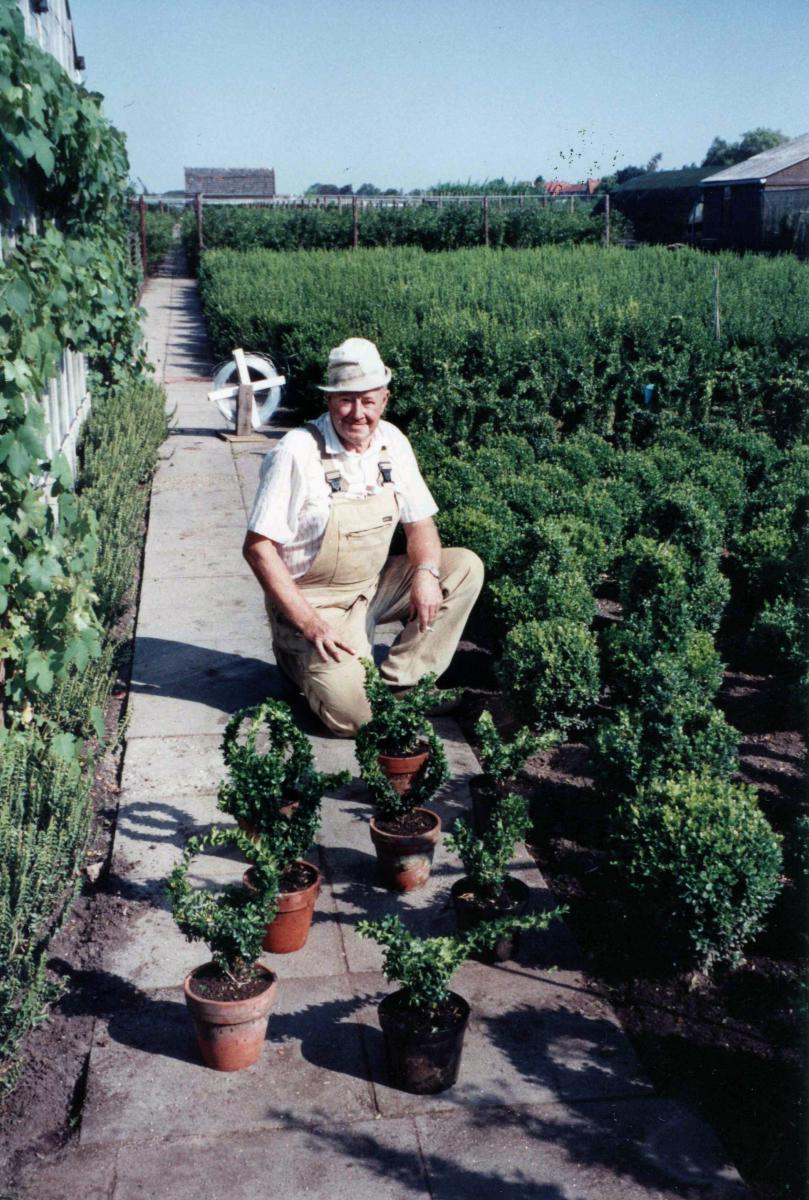

Topiarist Piet Oosterwijk, the author’s late father, with his boxwood topiary

3. REVIVALS AND SURVIVALS

Scathing criticism of unnatural ‘verdant sculpture’ resulted in wide-scale destruction. In 1780 the writer and taste-setter Horace Walpole recalled how the giants, monsters, heraldry and mottos in yew, box and holly in his ancestral garden had made way for the Englishness of the landscape garden of Charles Bridgeman and, later, William Kent and Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown.

Topiary, clearly, had became anathema in fashionable English circles.

Yet it could still be found in cottage gardens, and some estate owners maintained a stubborn fondness for this despised craft. In 1830 the Scottish-born landscape gardener William Barron was invited to Elvaston Castle in Derbyshire to create a garden with mature topiary trees and bushes transplanted from elsewhere. And a true revival began when the Arts and Crafts Movement of the late 19th century embraced topiary.

In 1910 Nathaniel Lloyd laid out his famous garden at Great Dixter in East Sussex, complete with topiary mustard pots. Ambrose Harding, owner of Madingley Hall in Cambridgeshire, had his yew topiary garden moved there from his previous home, Histon Manor, in 1927. Instrumental was the aptly named nurseryman Herbert J Cutbush, who regularly visited the Netherlands to buy yew and box topiary, especially from nurseries in and around Boskoop.

For me, topiary has a personal history. My father (pictured) and grandfather were boomkwekers (nurserymen) and topiarists in Boskoop. With my sister I grew up surrounded by boxwood chickens, peacocks, bears, squirrels, baskets, balls, cones and spirals. We even had our own boxwood teddy bears.

Then fashion changed and topiary disappeared from our lives, until it became trendy once more. In the summer of 1992 my father taught me topiary during an extended visit home. I scandalised him by creating a new shape – a hare – which was essentially a seated bear with long ears. My father disapproved until customers expressed interest. The hare became a stayer.

True survivors: topiary peacocks on top of a dragon at St Mary the Virgin Church, East Bedfont, in 2005

4. MAINTENANCE, NEGLECT AND RESTORATION

Topiary is labour-intensive.

It needs clipping twice a year to maintain its shape, which requires a good eye, a steady hand and patience. Large gardens with monumental hedges and topiary features require teams of trained gardeners equipped with shears and ladders. Unfortunately World Wars I and II saw dramatic reductions in available staff, and many estate gardens fell into neglect. This was particularly detrimental to topiary, throwing up all sorts of challenges to keep precious examples going.

For example, Yew Tree Avenue at Clipsham in Rutland is, in the main, over 200 years old. After Amos Alexander had started clipping the first trees near the gardener’s lodge in 1870, the estate owner ordered him to clip all 150 or so yew trees that formed the 500-yard carriage drive to Clipsham Hall (how he must have regretted his mistake, my father observed drily). After years of neglect the Forestry Commission eventually took over maintenance, but it proved too costly, and now the Clipsham Yew Tree Avenue Trust has undertaken renovation.

Another striking topiary restoration took place in East Bedfont in Greater London. In 1704, two yew trees flanking the entrance to the churchyard of St Mary the Virgin were shaped into two peacocks on top of a dragon – an act said to have been instigated by a rejected suitor. Local legend stated that ‘two over-bearing damsels... dismissed a suitor with such contempt that in revenge he had the trees trimmed to typify them as two proud and haughty peacocks.’ Restoration in 1865 was followed by another period of neglect, which saw the yews overgrown and unsightly. In 1990 a nurseryman from Boskoop, Ward van Klaveren, managed to restore the shapes after they’d had several years of dramatic chopping and pruning. The dates clipped into the lower tiers commemorate the creation and restoration.

Topiary at Levens Hall in Cumbria

5. HIGHLIGHTS AND VARIATIONS

Evergreens come in many varieties and once shaped into topiary they take on another dimension.

At Levens Hall we can admire not only the wonderful shapes, but also the different shades of green and yellow. At Knightshayes in Devon there is even a topiary fox hunt running across the top of a yew hedge. And the effect of winter snow covering topiary shapes wherever they are is spectacular.

Particularly imaginative is the yew topiary rendition of Georges Seurat’s famous pointillist painting Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte (1884–86) at the Topiary Park in Columbus in Ohio. Begun in 1989, it comprises 54 human figures, eight boats, three dogs, one monkey and a cat.

Money has helped create and maintain many a topiary garden. Yet sheer dedication and particular personalities have often played a major role. Until English Heritage took over, for example, gardener and odd-job man George Kelley spent two decades without pay struggling to maintain the Jacobean house and Edwardian gardens at Apethorpe Hall in Northamptonshire, creating some peculiar topiary shapes in the process.

Topiarists can have very strong views; the exact form of a peacock’s tail, for instance, can cause many arguments. Rude shapes can cause controversy, and topiary can even look sinister. In Tim Burton’s 1990 fantasy film Edward Scissorhands, the isolated hero inhabits a crumbling Gothic mansion inside a spooky topiary garden. Invited to live in suburbia, Edward delights the locals with his topiary skills but later destroys his creations in a rage.

Ultimately topiary is rather like Marmite: you either love it or hate it. Yet irrespective of whether you consider it an art or an aberration, it is important to recognise it for what it is: eye-catching and, above all, fun.

SOPHIE'S TOP TIPS

Create your own topiary

There are many ways to introduce topiary into your garden. You can buy ready-made topiary in specific shapes, or you can use wire frames to help you form a shape from an existing shrub. You can also create your own design with (or without) the help of wire, and even ‘cheat’ by growing ivy over a fancy frame. Some imaginative gardeners have clipped their privet hedges into wonderful shapes, including a locomotive.

Boxwood (Buxus sempervirens) is an attractive evergreen that can be used for hedges but can also be grown in tubs outdoors. Make sure you water them well: it is a mistake to think that rainfall will suffice for boxwood in tubs.

Boxwood used to be the ideal choice for true topiary until the arrival of boxwood blight, and then the spread of the box tree moth across Europe. There are ways of treating affected shrubs, but the moth’s larvae can defoliate a shrub in little or no time. Fortunately, resistant species are being developed.

Clip your topiary twice a year to create and maintain the desired shape: once in spring or early summer, and once in early autumn. I find wallpaper scissors the ideal tool for smaller jobs.

Places to visit

Famous for its historic topiary garden – the world’s oldest – is Levens Hall in Cumbria

Other sites with topiary gardens include Hever Castle in Kent, Madingley Hall in Cambridgeshire and Drummond Castle in Perthshire

In Belgium you will find the quirky Parc des Topiaires in Durbuy (south of Liège)

Good reads

There are many books on topiary – from picture books to guides on how to create your own. These include:

The Book of Topiary by Charles H Curtis and W Gibson, first published in 1904 but still in print or available digitally here or here

Mazes and Labyrinths by WH Matthews (1922), full of information and also available online

Topiarius, the annual journal of the European Boxwood and Topiary Society

About the Author

Sophie Oosterwijk

Sophie Oosterwijk grew up on the family nursery in Boskoop in the Netherlands. After studying English literature at Leiden, she moved to England and studied medieval studies at York. She gained a PhD in art history at Leicester, and a second PhD, in English literature, at Leiden. After teaching at universities, including St Andrews and Cambridge, she moved back to the Netherlands, where she works as a freelance lecturer and researcher. Her lecture topics for The Arts Society include Birds, beasts and box: the art of topiary, The history and collection of the Rijksmuseum and Sinner or saint? The changing image of Mary Magdalene

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition