This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

Become an Instant Expert on the Taj Mahal

Become an Instant Expert on the Taj Mahal

22 Jun 2021

Mughal art masterpiece and a site on the bucket list of millions of travellers, the Taj Mahal is said to have been built as a monument to love. Our expert, Arts Society Lecturer Georgina Bexon, examines the evidence

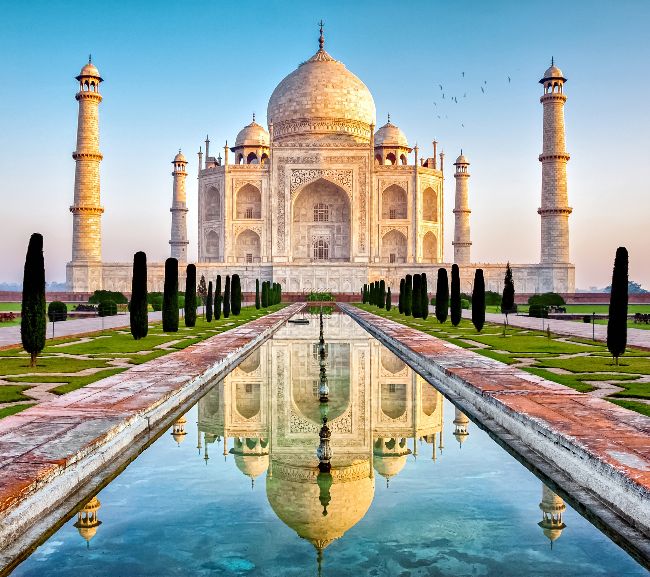

The Taj Mahal, in Agra in the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh

‘The Taj Mahal rises above the banks of the river like a solitary tear suspended on the cheek of time’

Rabindranath Tagore, Bengali Nobel Laureate, Poet, 1861–1941

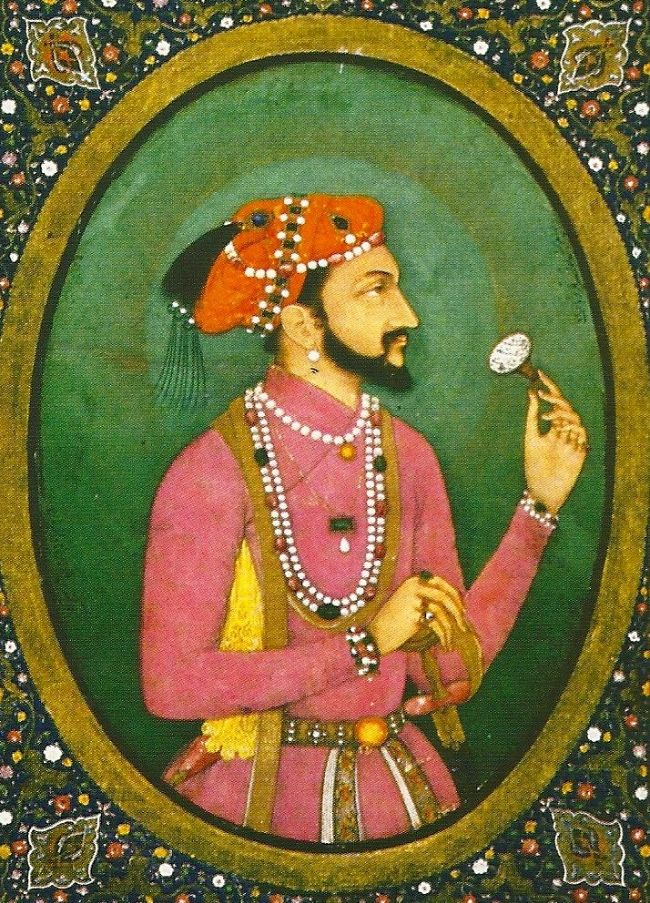

A 17th-century portrait of Shah Jahan

1. SITE OF WONDER

The Mughal emperors who ruled a swathe of India from the 16th to 18th centuries were known for their love of beauty and opulence. They built magnificent palaces and commissioned glorious artworks, but the greatest achievement of all was the construction of the Taj Mahal.

This royal tomb was built by the fifth Mughal emperor, Shah Jahan, as an elegy for his wife, Mumtaz Mahal, when she died in 1631. It is situated on the Yamuna River near Agra, the Mughal capital, and, with its elegant dome and surrounding minarets expressing a perfect sense of harmony and balance, has been called a ‘love poem in marble’.

In 1983 the Taj Mahal was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site, being described as ‘the jewel of Muslim art in India and one of the universally admired masterpieces of the world’.

Completed around 1648, this wonderful edifice, which always elicits gasps of admiration, took some 17 years to build. A further five years were devoted to the gardens, outer buildings and a grand gateway.

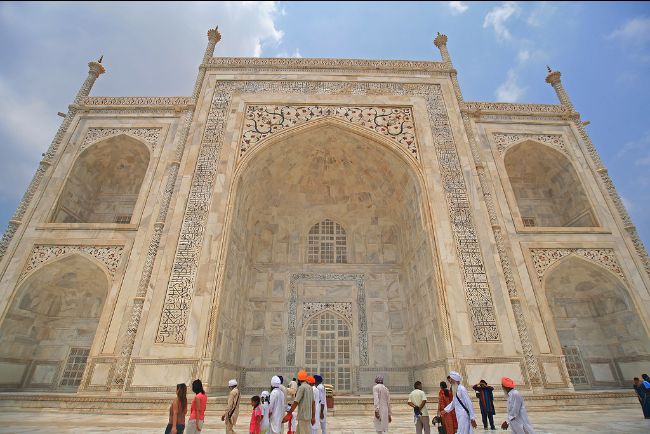

Constructed of brick covered with glistening white marble and inlaid with gems, the monument’s construction was the triumph of its age. A team of over 20,000 men was assembled, made up of stone carvers from Bukhara, stonecutters from Balochistan, mosaicists from southern India and many more skilled artisans, sculptors, inlayers and calligraphers. The heavy white marble was transported by 10,000 elephants from Makrana, 200 miles away in Rajasthan.

Highly skilled inlayers created the pietra dura (intricately patterned marble inlay work) that covers the interior. Over 40 types of precious and semi-precious stones were used, creating beautiful depictions of plants and flowers, geometrical and arabesque patterns and calligraphic verses from the Koran. These materials were shipped from all over Asia: jasper from the Punjab, jade and crystal from China, turquoise from Tibet, lapis lazuli from Afghanistan, sapphires from Sri Lanka, carnelian from Arabia and garnets and diamonds from Bundelkhand, central India.

The view of the Taj Mahal from the lawn

2. A MONUMENT TO LOVE...

Mumtaz Mahal died giving birth to her 14th child, while accompanying her husband on a military campaign in the Deccan, central India. The story goes that Shah Jahan was so grief-stricken at the death of his favourite wife (Mumtaz Mahal meaning ‘The Chosen one of the Palace’) that he retired to his tent and wept inconsolably for eight days. When he finally emerged, looking older by decades, his hair had turned white and he had partially lost his eyesight.

The tale is apocryphal of course; no hard evidence exists. What we do know from historic texts is that Shah Jahan immediately commenced work on a grand tomb that would ensure that the name of Mumtaz Mahal, and his great love for her, would live forever. Having achieved his grand memorial, Shah Jahan instructed that upon his death he should be buried beside his beloved wife.

Shah Jahan’s life ended tragically. His son, Aurangzeb, forced him to abdicate, imprisoning him for the rest of his life. Despite this, perhaps in a moment of remorse, Aurangzeb fulfilled Shah Jahan’s final wish. Inside the Taj Mahal, Shah Jahan and Mumtaz Mahal lie side by side in a simple crypt in a quiet space at garden level. The crypt is plain, as Islam forbids elaborate decoration of graves. Up above, the far grander and elaborate cenotaphs honouring the pair are set in an eight-sided chamber ornamented with pietra dura and marble lattice screens. The tombs are covered in intricate patterns of vines and flowers.

Floral inlay work at the Taj Mahal

3. ...OR A MONUMENT TO PROPAGANDA?

The iconic status of the Taj Mahal as the eternal monument to love and Shah Jahan’s reputation as an arch-romantic warrants investigation.

Firstly, there is no doubt that the monument’s misty-eyed celebrity has grown over the centuries. Particular interest came in the early 19th century, during the British Romantic period, when the fascination for everything Indian reached almost fever pitch, further imbuing the monument with its enduring romantic appeal.

Secondly, contemporary accounts show that as a leader Shah Jahan was more ruthless than romantic. When he ascended the throne in 1628 as Prince Khurram, he took the regnal name of Shah Jahan, meaning 'King of the World'. His choice of title speaks clearly of both his vaulting ambition and his early skills of self-promotion.

Like many Mughal emperors he was an astute and decisive politician. Imperial displays of brutality as hallmarks of power were expected, even demanded, as kingly qualities by court and subjects. Indeed, Shah Jahan was a vicious opponent both on and off the battlefield. He engaged in a bitter power struggle to claim the throne, which included murdering his older brother, before crowning himself emperor at Agra in 1628.

As a result, we can reasonably view the construction of the Taj Mahal as an exercise in political image-making.

In terms of design, the pure symmetry symbolises absolute power – the perfection of Mughal leadership. The grand scale and opulence clearly define the emperor’s supremacy, revealing the monument as a visible and tangible sign of dynastic power. So, perhaps disappointingly for some, the narrative of the mausoleum as a gesture of grand passion is at least as much fiction as fact.

Inside the Taj Mahal complex

4. SETTING THE RECORD STRAIGHT

Myths about the Taj Mahal abound, the products of vivid imagination and invention. Some have been retold so many times by local guides that they are often accepted as historical fact.

Yet there is no evidence to support the following stories:

That Shah Jahan planned to construct an identical mirror image of the monument across the river in black marble.

That the emperor severed the hands or gouged the eyes of his builders and artisans, to prevent them replicating their work elsewhere, or for any other monarch.

That Mumtaz Mahal was simply a decorative consort and mother. She actually exercised significant political power and influence at court. She also organised care and funds for the poor, always accompanied the emperor into battle, and was an excellent chess player, frequently defeating her husband.

Finally, it is a misnomer to describe the building style of the Taj Mahal as ‘Mughal’. It is better termed as ‘Indo-Islamic’, which is a blend of Indian, Persian and Islamic styles. For example, the finial atop the great dome combines the Islamic symbol of the crescent moon with the Hindu trident of the god Shiva.

It is supposed that Shah Jahan incorporated local design elements to please his Indian subjects. For a long time Mughal policy had adopted a tolerant, inclusive approach to the Hindu population; local Rajput nobles held positions at court and in the army and intermarried with Mughal families. Shah Jahan’s mother had been a Hindu from Rajasthan.

The Taj Mahal’s soaring walls of decorated white marble

5. THE TAJ MAHAL TODAY

Following the decline of the Mughal Empire, the Taj Mahal fell into disrepair. It was vandalised and precious gems and other items looted.

At the turn of the 19th century Lord Curzon, the British Viceroy of India, ordered a major restoration. Sadly, at the same time, the beautiful Mughal gardens were redesigned in a British-style layout, which remains to this day.

The mausoleum has been cared for ever since by the Archaeological Survey of India (founded in 1861). Today, like many world landmarks, this special site is under threat from the very people who come to admire it. Three million visitors a year breathing on the interior cause excessive humidity, which is damaging the marble.

The edifice is also suffering the effects of pollutants from nearby factories and local traffic and, despite some preventative measures, the once gleaming white marble facia is turning a drab yellowish colour. A further concern is the effect of the nearby Yamuna River drying up periodically, with possible impact on the foundations. Historians, experts and activists are currently lobbying the Indian government for action.

On a happier note, the Taj Mahal is now the subject of a modern and historic democratisation process. While millions of visitors have access to the monument every year, people from its Mughal past are also, curiously, coming to light.

In 2011 previously undocumented inscriptions at the mausoleum were translated. The names of 670 of the 17th-century artisans to have worked on the Taj Mahal emerged. Researchers have launched a project to attempt to track down their descendants.

With this fascinating development, the Taj Mahal speaks to us from the past. In doing so it becomes less an edifice of an old ruling class, and more a monument of the people.

GEORGINA'S TOP TIPS

Explore...

When restrictions allow, other important Mughal sites to visit in South Asia include:

Akbar's Tomb, Agra: the magnificent tomb of the Mughal emperor Akbar, who died in 1605

Hamayun’s Tomb, Delhi: built in 1570, the first of the dynastic mausoleums, and now a UNESCO World Heritage Site

The Red Fort, Delhi: built by Shah Jahan, the fort is also a UNESCO World Heritage Site

Jahangir’s Tomb, Lahore, Pakistan: tomb of another powerful ruler, who died in 1627

See...

Mughal art closer to home; among the UK sites with such works are:

The Nehru Gallery, Victoria and Albert Museum, London

The Sir Joseph Hotung Gallery, The British Museum, London

The Clive Museum, Powis Castle, Powys, Wales

And examples of Indo-Saracenic architecture in the UK: Sezincote House, Nr Moreton-in-Marsh, Gloucestershire and Brighton Pavilion, East Sussex

Enjoy...

A film about the Mughal Empire. The following can be found via digital outlets:

Jodhaa Akbar is a sumptuous 2008 film, which recounts the love story between the Mughal Emperor Akbar and the Rajput Princess Jodhaa. Find it on Netflix

The Kingmaker of the Mughal Empire is an Indian docudrama made in 2018, available on Amazon Prime

The Great Moghuls, a 1990 informative six-part Channel 4 documentary series hosted by Bamber Gascoigne, covering the rise of the Moghul Empire; see it on YouTube

About the Author

Georgina Bexon

Georgina Bexon is an art historian specialising in South Asian art. Her practice includes lecturing, writing, consulting and collecting and she has developed a network of gallery and artist connections in Europe, the USA and India, which she visits regularly. She is consultant art historian at the Oriental Club in London, an official tour guide at Tate Modern, and a guest speaker on cruise ships, for whom she has developed a series of art talks relating to Asian and Pacific destinations. She has been a visiting lecturer at UK universities, presents talks at leading art institutions, including Christie’s Education, New York and the Moscow Museum of Modern Art, and speaks at international art conferences. Among Georgina’s talks for The Arts Society are Monument to love – the story of the Taj Mahal, Art of the Mughal world, Koh-i-Noor – the most famous diamond in the world and Rituals and riches – the history of the south Indian temple.

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition