This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

Inside Bob and Roberta’s world

Inside Bob and Roberta’s world

15 Feb 2021

Art empowers children, but we must transform the way we teach it, says artist and activist Bob and Roberta Smith. He believes every human being is an artist, even if they have to steal to be one. Sue Herdman meets him to find out why

Photography by John Millar

Bob and Roberta Smith shares a story in his latest book, You Are An Artist, which is telling. He describes how, when small, his mother taught him to draw by sketching a Christmas pudding. ‘Draw the custard first,’ she said, ‘then underneath, draw in the pudding.’ On it progresses, mother gently nudging child to add to his artwork a plate, holly atop the pudding, and friends. ‘Let’s invite everyone to the party,’ she tells her son. ‘Art is an invitation.’ He has been drawing on that statement ever since.

Smith (real name Patrick Brill) is an artist, activist, author, broadcaster, educator, musician and skip diver. He famously favours text as medium, in the form of sign painting, doing so mischievously, passionately, sometimes reassuringly. The Royal Academy’s 2020 Summer Exhibition featured one such work by this Royal Academician, which offered balm in our nervy Covid times. A reworking of one of his mantras, it stated: There Is Still Art, There Is Still Hope. Not all of Smith’s slogans – painted on doors and boards discarded by others – are gentle. Most are politically charged. Among his best known are his 1997 Make Art Not War and his 2011 Letter to Michael Gove.

Art is in All of Us and Draw Hope, 2020

In the latter he charged the then Secretary of State for Education with the ‘destruction of Britain’s ability to draw, design and sing’. In addition to his agitprop ‘letter’, Smith took things further. He stood in the 2015 General Election against Gove, earning space on the public stage to get ‘access to arts’ into the election conversation. The whole exercise, he muses now, ‘was really a large artwork’.

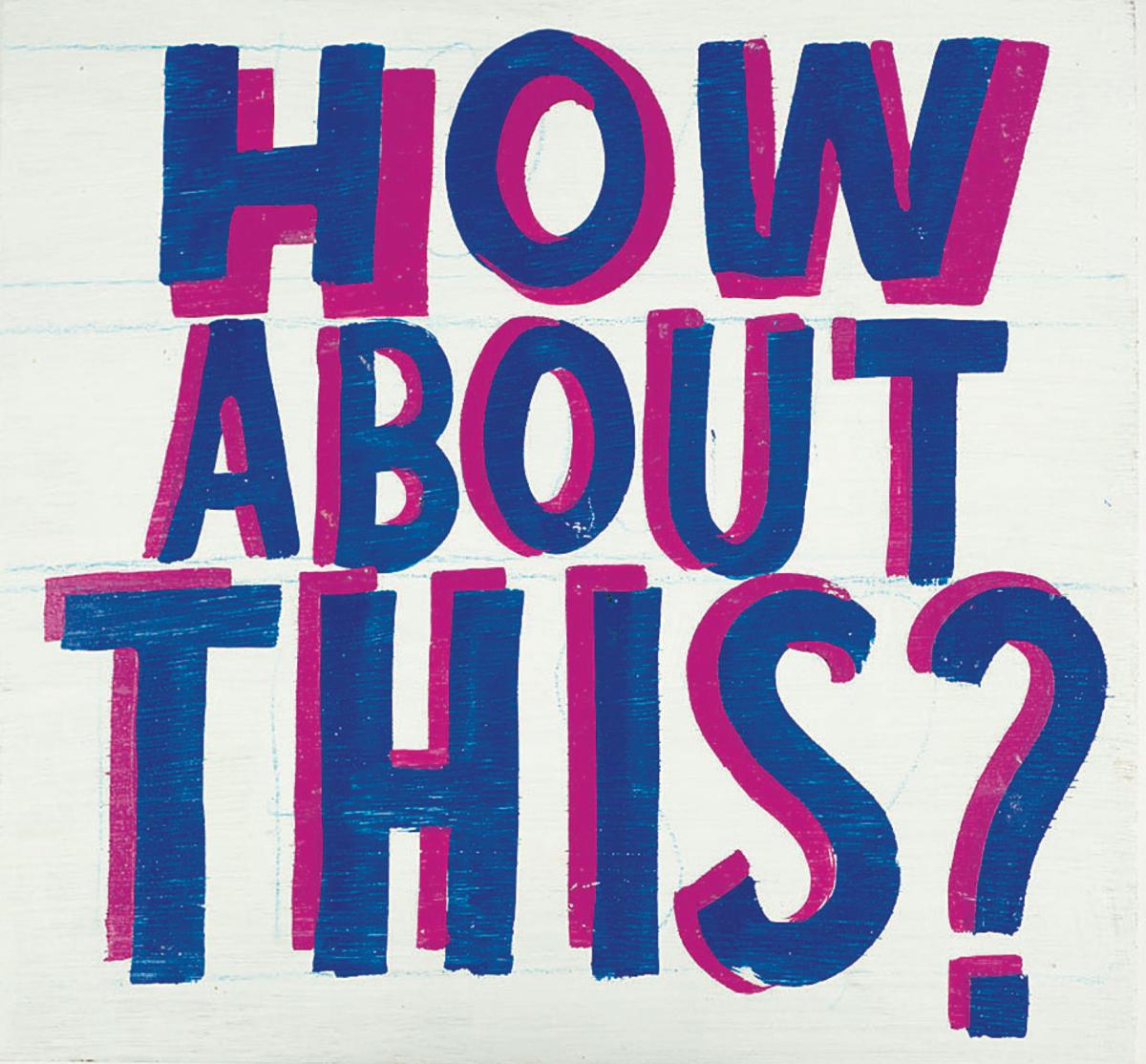

Smith is passionate about arts education. He wants us to champion its power; to understand the way visuality can play a role in early speech and to see how exciting results come from asking the simple question: ‘How about this?’ ‘It’s what artists and designers are saying every time they pick up a paintbrush or pencil,’ he states. When we meet, he’s on sunny but thoughtful form, coming via Zoom from his colourful east London kitchen. ‘It’s important that artists speak about issues like this,’ he states. ‘In terms of its aims, the coalition government’s EBacc wasn’t a bad thing, but its impact on how the curriculum was organised and how schools get ranked was a disaster for the arts. It’s easy for artists of standing to become a little ivory-towerish, and not get involved in politics. But it’s useful, when you’ve got some authority, to make a stand about things you know about.’ And Smith knows about arts education.

All Schools Should Be Art Schools

A START IN ART

The genesis for this lies in his early experiences. Born in 1963, his childhood home was centred on art. Even his school had an arty slant: Brandlehow Primary in Putney, now Grade II listed, was designed by that great modernist Ernö Goldfinger, in optimistic post-war London. Smith’s father, the landscape painter Frederick Brill, was head of the Chelsea School of Art. His mother, Deirdre Borlase, was an artist who exhibited at the Royal Academy’s Summer Exhibition. ‘Both came from working-class backgrounds and I don’t know how they discovered they could draw. But that skill propelled them to 1930s art schools and transformed their lives. There was no sense in our house that you couldn’t earn a living making art.’ An early memory is of being taken to an exhibition by his mother when aged around six. ‘There, in the foyer, the process of printmaking was happening. I was fascinated. The business of the making of art has stayed with me since that moment.’

'Don’t tell the student to look at Duchamp. Ask instead what it is they want to do. Ask them how they are going to throw pebbles into the pool of culture that will cause ripples.'

A patron of The Big Draw and the National Society for Education in Art and Design, Smith has not only made art all his life, but for over 30 years has taught it too. Currently associate professor at London Metropolitan University, he is an ardent believer in student-centred education. ‘Don’t tell the student to look at Duchamp,’ he states over our virtual coffee, ‘ask instead what it is they want to do. Ask them how they are going to throw pebbles into the pool of culture that will cause ripples. There has to be a transformation in the way we teach art. It needs to be built on ideas of self-expression – that’s the way it is done in the best art education. Make more. Encourage students to manifest the things they feel are important.’

Smith is all about inclusivity. He extols the power of ‘creating art that has a workshop element to it, having an educational element in a gallery, where people can make art and engage’. His chosen pseudonym is spurred by this. Originally conceived as ‘Bob Smith’ – a random name applied to his early text works – ‘Roberta’ was added when working alongside his sister Roberta; he then kept the name when going solo. His theory is that anyone can be a Bob and Roberta Smith. ‘In fact, for a while, in the 1980s, two couples, one in Japan and one in Germany, called themselves just that and used to send me their art.’ Everyone, as he will never tire of saying, is an artist.

Feel the Image and Feel the Colour, 2020

The only problem with this is that along the way we forget that. Smith wants to put that to rights. You Are an Artist is both a revealing exploration of art practice, and a collection of over 40 practical exercises, or ‘creative provocations’, to encourage rediscovery of our latent gifts. Under his gently anarchic, always humorous guidance, you will come to view the humble plastic milk bottle as a beautiful object. I, for one, hadn’t thought of pasta as Italian folk art before. Nor considered the possibilities of making a coffin for an imaginary pet, indulging in some creative ironing or, yes, stealing.

Does this refer to his skip surveys for boards to paint? ‘I am not asking you to consider a major theft here,’ states the artist. The exercise of ‘stealing’ is, he explains in the book, ‘more about thinking when learning. When we learn, we are in some sense mastering and replicating others’ works and ideas.’ So it’s less about larceny, more about ‘stealing’, or reflecting on, the ideas of others. Smith likes the concept of artists as scavengers ‘because they operate on the outside of society, picking up what is useful for their practice to get by’.

INSIDER, OUTSIDER

Smith has a sense of the outsider about him. With a firm foothold in the established art elite (an OBE for services to art, a former trustee at Tate), his practice also has a freedom, an ability to ‘poke’ with his slogans. He stands up and out on uncomfortable truths, but always with the end goal of inclusivity. His practice embraces film, radio, documentary, writing and music. His bands include The Ken Ardley Playboys (say it quickly) and The Apathy Band (lead singer, Smith’s wife, the artist Jessica Voorsanger), an arts advocacy and experimental spoken word group that usually can’t be bothered to rehearse.

Smith’s weekly Resonance FM programme broadcasts each Tuesday night. The station is a non-profit community set-up, specialising in the arts; the show, a quirky listening experience, somehow managing to be both cosy and lawless. He cites it as one of the things that got him through the rigours of 2020. Another is his (huge) latest project, a collaborative commission from Tate and the Peabody Trust called the Thamesmead Codex. This involved interviewing people from the troubled 1960s London Thamesmead (backdrop to, among others, Kubrick’s dystopian A Clockwork Orange). The broader context had been to talk about Modernism, but naturally Covid elbowed in. Those conversations – many particularly powerful – have been transcribed onto panels to create an artwork 24 metres square. It features in part a return to some figurative painting and goes on show at Thamesmead this spring, with plans for a showing at Tate Modern later this year.

How About This?, 2020

How About This?, 2020

Listening to his interviewees has been illuminating. Smith is a considered listener. He’s concerned about the effect of the pandemic’s severance of access to art on estates such as this, and in the wider world. ‘Think of all those kids who haven’t seen an amazing piece of new theatre; who haven’t been excited to lift a guitar for the first time; who haven’t been to an exhibition that spurs them to think: “I can do this.” That’s a huge loss. When we have access to the arts – when you are teaching art – you’re enabling something fundamental; you are helping people realise who and what they are. Teaching art is akin to a human right; art teachers are human rights workers. Art enables us to advocate for ourselves, using whatever medium works for us. It helps us process things, letting us sink into our imaginations. It’s about looking and listening to the world and asking: “Is that right?” Artists are truth seekers.’ The less art you have, the fewer truth seekers.’ Perhaps this is why another of Smith’s mantras and artworks, Make Your Own Damn Art, has its own kind of power right now. It may sound like a fist-pumping shout, but the ethos behind it is charged with hope. Truly, go out and make art. ‘It makes the world,’ says Smith, ‘a better place.’

SEE

For news on the showing of Thamesmead Codex, see thamesmeadnow.org.uk

FOR MORE ON

Bob and Roberta Smith’s practice, see bobandrobertasmith.co.uk

READ

You Are an Artist is published by Thames & Hudson; thamesandhudson.com

Sue Herdman is editor-in-chief of The Arts Society Magazine

About the Author

Sue Herdman

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition