This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

Josef and Anni Albers: Partners & Pioneers

Josef and Anni Albers: Partners & Pioneers

15 Dec 2020

She was the weaver and textile designer who led us to reconsider fabrics as an art form. He was an influential teacher, painter, designer and colourist. Together Anni and Josef Albers were 20th-century innovators. Sue Herdman asks Nicholas Fox Weber, author of a new book on the pair, about their work, partnership and the myths that surrounded them.

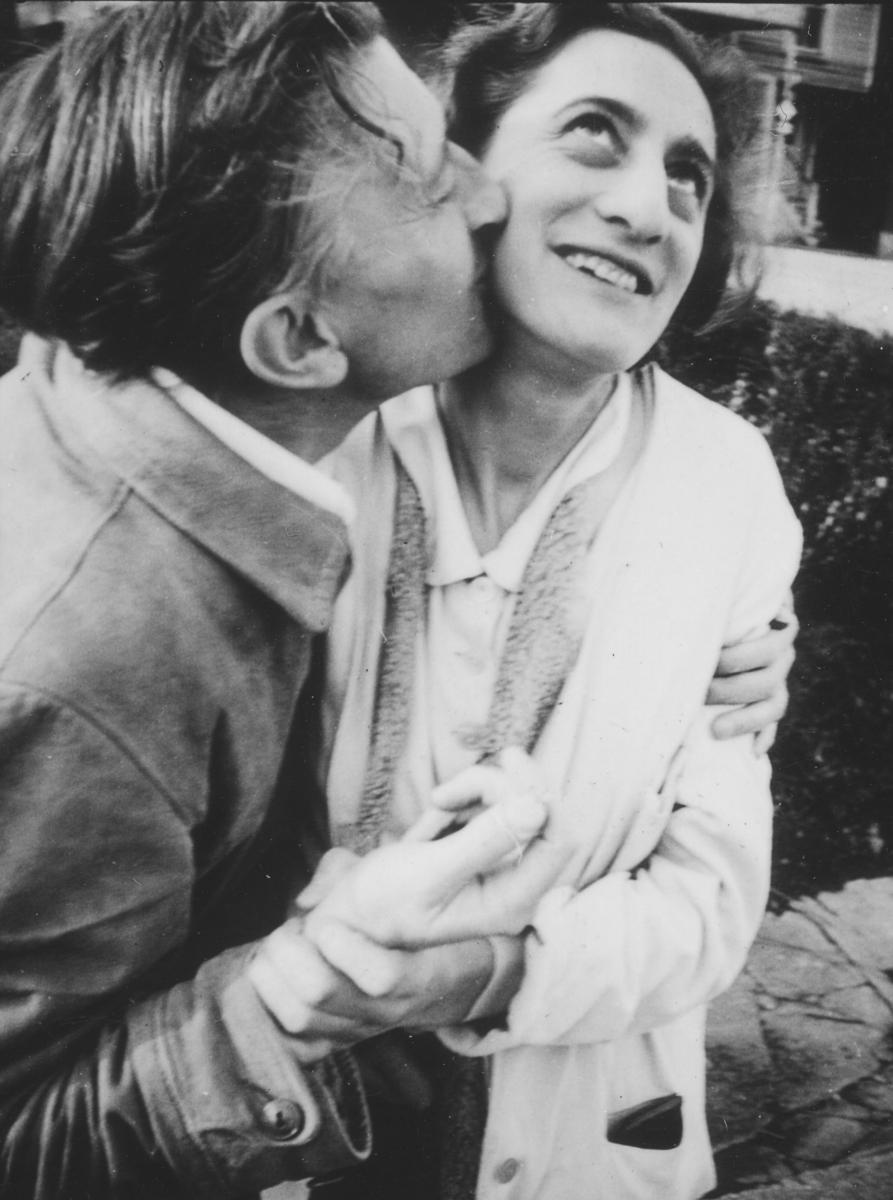

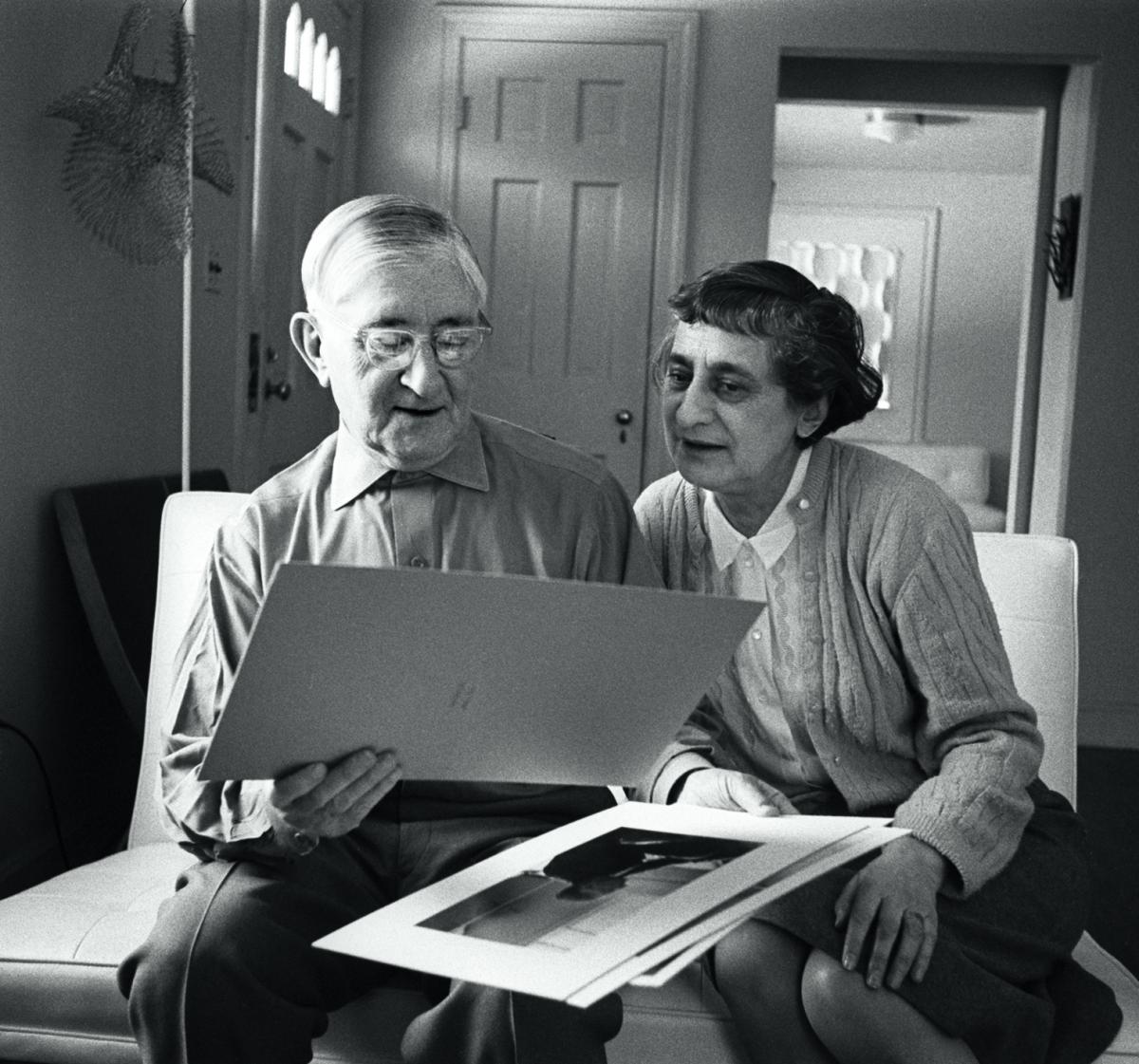

Josef and Anni Albers, c.1935. Courtesy and © 2020 The Josef And Anni Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/DACS, London

Josef and Anni Albers, c.1935. Courtesy and © 2020 The Josef And Anni Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/DACS, London

You knew Anni and Josef Albers personally. What are your recollections of them?

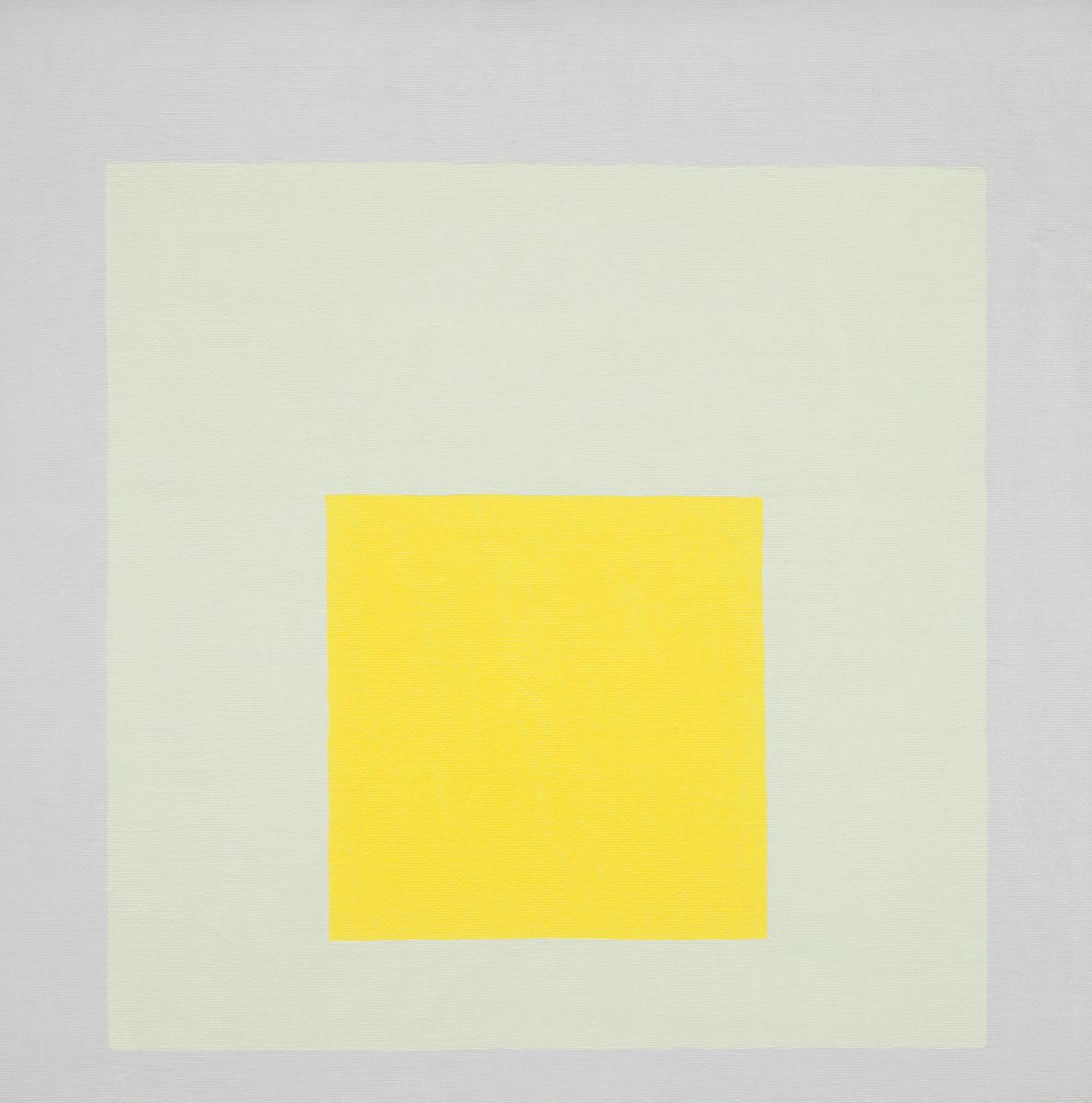

I was fortunate to spend time with them in their last years and they appear, in hindsight, all the more remarkable. They were youthful and still working. Josef didn’t start his Homage to the Square series (his paintings of three or four nested squares of solid colours, of which he made more than 2,000) until he was 62. They were like a two-person religious sect. They led a confined, organised life and dressed simply. They liked the affordable (at one time they had recycled car seats as a sofa), and had no patience with pretension. Art and universal truths were their primary focus. Josef strove to explore the miracles of colour, wanting to reveal them to the world endlessly. Anni was obsessed with the quality – the candour – of weaving; what it should reveal about the medium and how it should show the truth in the way a textile holds together.

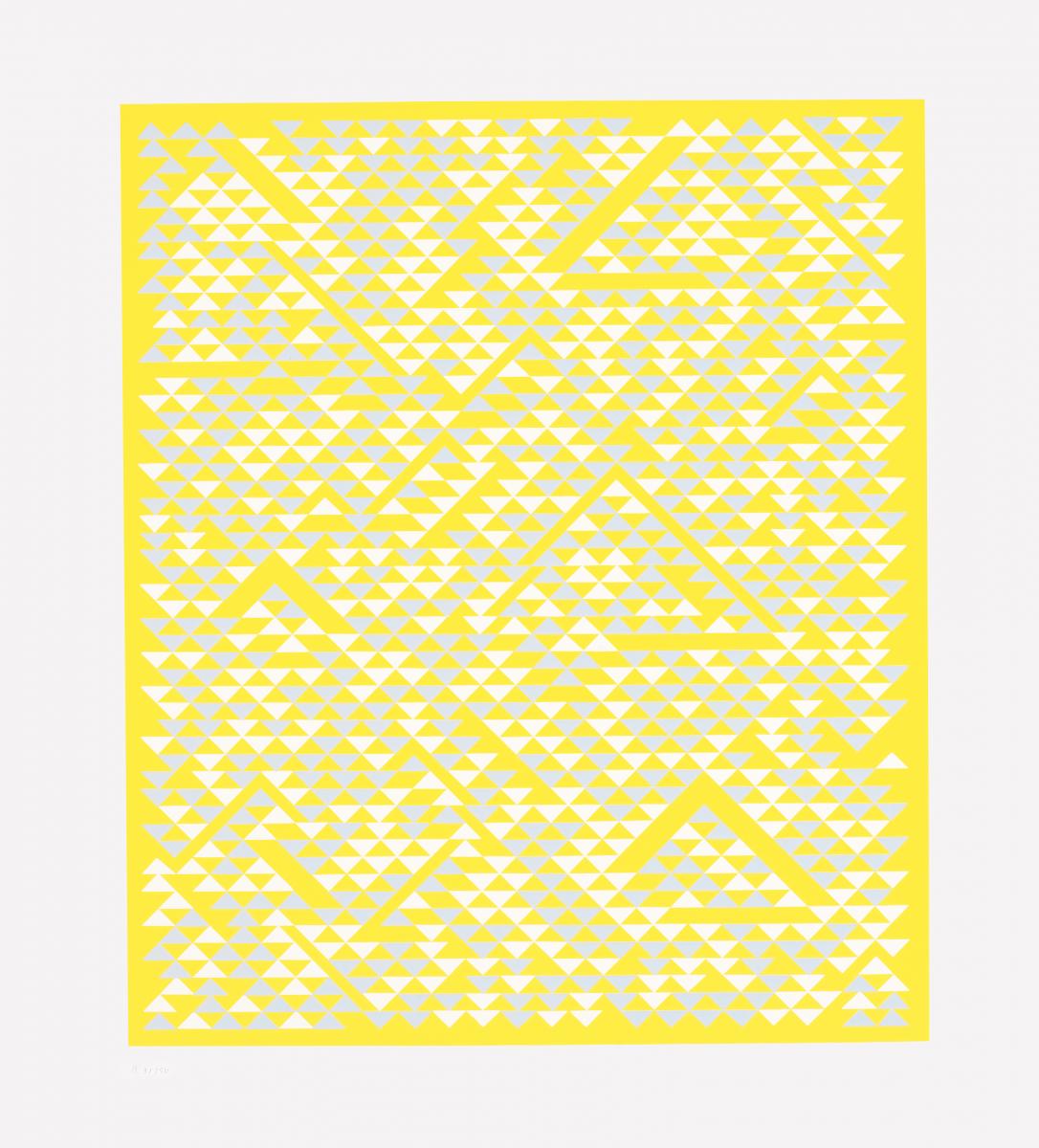

Anni Albers screenprint, B, 1968. 55.8 × 47.8cm. Photo: Tim Nighswander/Imaging4art © 2020 The Josef And Anni Albers Foundation/ Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/DACS, London

Anni Albers screenprint, B, 1968. 55.8 × 47.8cm. Photo: Tim Nighswander/Imaging4art © 2020 The Josef And Anni Albers Foundation/ Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/DACS, London

How would you describe their partnership?

They worked on their own terms, in everything they did, including their marriage, which was complex. Anni recalled Josef coming to her once to ask for help in ending an affair. ‘I was very proud to be able to help him,’ she said. An unusual attitude – yet what I understand now is just how important their marriage was in liberating them to be creative. They supported each other’s priorities. They understood each other’s need to make art. Their work complemented each other’s. But if their art was shown with that of other artists, for instance Josef’s with Donald Judd’s, it was like trying to listen to two musical scores at once.

Josef Albers, Study for Homage to the Square: Impact, 1965. Oil on Masonite; 60.5 × 60.5cm. Courtesy The Josef Albers Museum Quadrat Bottrop. © 2020 The Josef And Anni Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/DACS, London

Josef Albers, Study for Homage to the Square: Impact, 1965. Oil on Masonite; 60.5 × 60.5cm. Courtesy The Josef Albers Museum Quadrat Bottrop. © 2020 The Josef And Anni Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/DACS, London

Where should we place the Alberses in art history?

It’s important to get away from the idea of ‘movements’. There are no ‘isms’ that can be associated with them. They can’t be typecast. Yes, they are associated with the Bauhaus, where they met, but they were just two very original artists, producing art of integrity and energy. Their closest affinities were to artists that had preceded them by centuries.

‘THEY WERE LIKE A TWO-PERSON RELIGIOUS SECT. THEY LED A CONFINED, ORGANISED LIFE AND DRESSED SIMPLY... THEY HAD NO PATIENCE WITH PRETENSION. ART WAS THEIR PRIMARY FOCUS’

If coming to Anni’s work for the first time, which pieces should we seek?

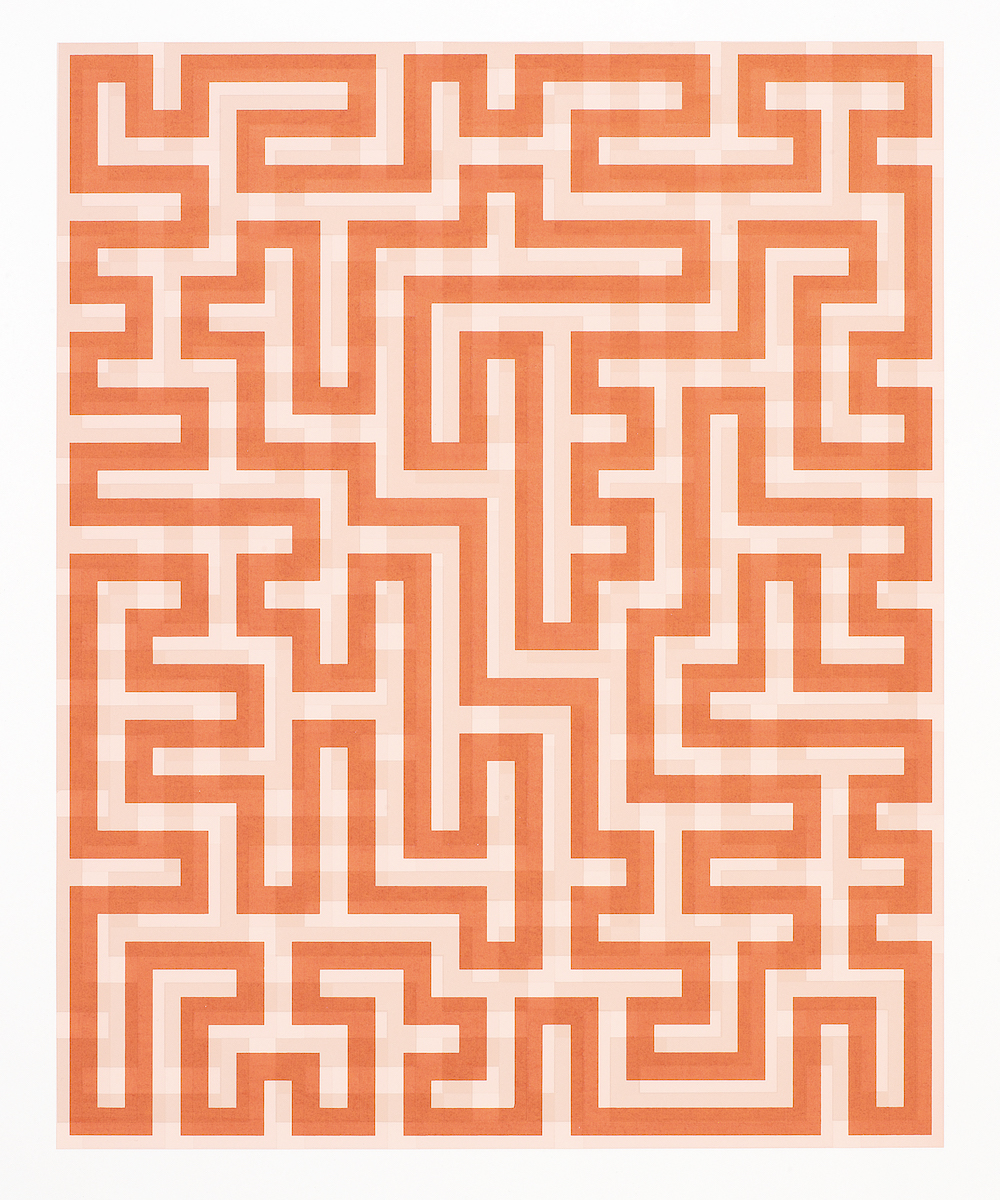

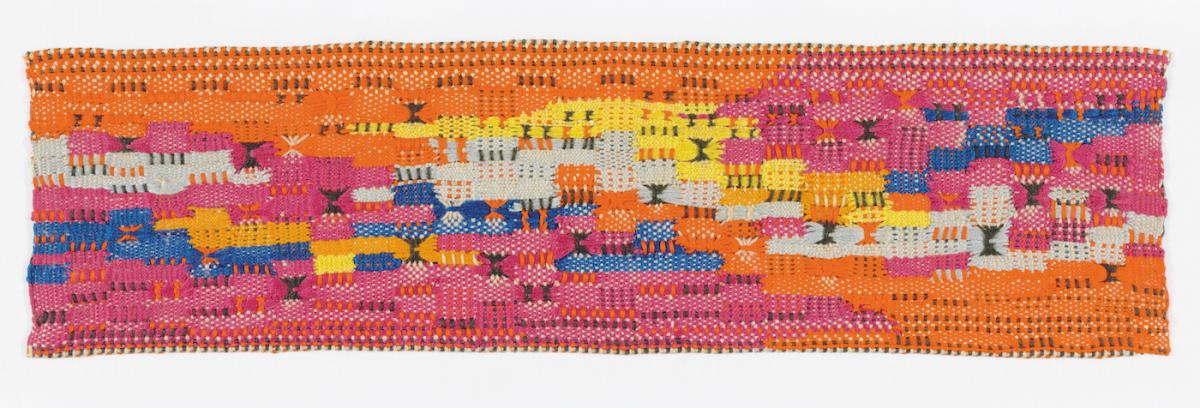

Start with a couple of her simple, functional Bauhaus textiles, of the type where the entire design is thread. What gives the piece its structure, gives it its beauty. Move on to her 1927 Untitled wall hanging, now owned by Harvard Art Museums. Anni thought it was the best of her Bauhaus period. Then there are the room dividers she made for her 1949 exhibition at MoMA. Such an inventive use of materials, including cellophane, horsehair and jute. See her 1958 South of the Border. Just five inches high, it’s like a mural, with such vibrancy. It’s in the realm of her great making. Her Meander prints are remarkable for the way they depend so much on the process of printmaking. And I would direct you to her later wall prints. Who else but an older Anni Albers would utilise the tremor of her hands to create something so beautiful?

Josef Albers, Etude: Red-Violet (Christmas Shopping), 1935. Courtesy and © 2020 The Josef And Anni Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/DACS, London

Josef Albers, Etude: Red-Violet (Christmas Shopping), 1935. Courtesy and © 2020 The Josef And Anni Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/DACS, London

And of Josef’s work?

Start with his sparse drawing of two geese, c.1917. He used minimal means to maximum effect – that is how he always worked. Seek out his Bauhaus assemblages of broken glass shards and stained glass, and his photo collages of a similar time. I like the one of Walter Gropius at the beach in Biarritz. You can see Josef ’s playfulness in his juxtaposition of the images. For his Black Mountain College years go to his small 1935 Etude: Red-Violet (Christmas Shopping). It is so true to abstraction. If it was on a magazine cover now no one would guess that it was a Josef Albers, nor when it was made. Of his Homage to the Square series, for me, it is his pair, Despite Mist (1967 and 1968). The only physical difference between them is the outermost colour. And then see his linear series, Structural Constellations. So simple: thin, straight lines create compositions that are optical illusions. You can see the image one way, then another and can’t reconcile how you can see two things simultaneously.

Josef And Anni Albers In Their Living Room, 8 North Forest Circle, New Haven, Connecticut, c.1965. Photo © John T Hill. Courtesy The Josef And Anni Albers Foundation

Josef And Anni Albers In Their Living Room, 8 North Forest Circle, New Haven, Connecticut, c.1965. Photo © John T Hill. Courtesy The Josef And Anni Albers Foundation

Why was colour so important to Josef?

He was fascinated by its deceptive qualities and its magic. He arranged colours in a way to make a perfectly flat colour appear shaded. Again, he created illusions. Take a work where he has dark red in the middle and pale tan outside. You begin to see the illusion of that red on the outside of that tan square that surrounds it, but not on the part of the tan square that is closest to it. An impossibility occurs. In maths, 1 + 1 + 1 = 3. But for Josef, in art, the same sum equalled infinity.

An Anni Albers screenprint, Red Meander II, 1970–71, © 2020 The Josef And Anni Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/DACS, London

An Anni Albers screenprint, Red Meander II, 1970–71, © 2020 The Josef And Anni Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/DACS, London

What myths about the pair would you debunk?

There are so many. Firstly, Anni did not weave Josef ’s suits. There was talk of Josef being harsh: a rumour, for instance, that he had forced the artist father of actor Robert De Niro to be so unhappy that he left art school. It’s not true (Robert De Niro Senior, by the way, was a good painter). But both Anni and Josef were opinionated. Josef spoke of Marcel Duchamp’s work in the way he spoke about Hitler. He thought Duchamp’s influence gave people license to be second-rate artists. That, to him, was unacceptable. And art history does Anni a disservice when it says she was forced into textiles at the Bauhaus. Working with oils and canvas or equivalent there meant wall painting. Anni had an inherited physical condition that saw her walk with a limp; she could not climb a ladder for such painting. But once in the textiles space she saw how to use a loom inventively. It became a treasure trove of possibilities.

Anni Albers, cotton and wool, South of the Border, 1958. 10.5 × 38.7cm. Courtesy Of The Baltimore Museum Of Art. © 2020 The Josef And Anni Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/DACS, London

Anni Albers, cotton and wool, South of the Border, 1958. 10.5 × 38.7cm. Courtesy Of The Baltimore Museum Of Art. © 2020 The Josef And Anni Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/DACS, London

What does the Alberses’ art offer a 21st-century audience?

One of Anni’s favoured books was Wilhelm Worringer’s 1908 Abstraction and Empathy. To use his term, their art offers ‘visual resting places’. For me, their work offers a marvellous diversion. Both Anni and Josef felt that art, at its best, does not evoke the tragic. This year our foundation worked with St Mary’s Hospital, Paddington to take the Alberses’ art as a frame to redo the paediatric intensive care unit. Josef considered yellow the colour of healing. The unit was subsequently used to care for Covid-19 patients. Our hope is that the Alberses’ approach to art now provides at least a few minutes’ reprieve from a situation in those spaces. If art is going to have a place for us, it is the creation of an ‘other’ in which we can lose ourselves – in the intricacies of an Anni Albers-designed wallpaper, or the colours Josef loved. It’s that ‘other’ that the Alberses sought in their work. And we have particular need of that ‘other’ in these times.

FIND OUT MORE

Anni & Josef Albers: Equal and Unequal by Nicholas Fox Weber is published by Phaidon; phaidon.com

For more – and news of 2021 exhibitions – see The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation; albersfoundation.org

Sue Herdman is editor-in-chief, The Arts Society Magazine

About the Author

Sue Herdman

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition