Dear Arts Society Member

Welcome to our February newsletter.

24 Aug 2020

Unfurled: the Chinese handscroll

A significant difference between Eastern and Western painting lies in the format. Unlike Western paintings, which are hung on walls and continuously visible to the eye, most Chinese paintings are not meant to be on constant view but are brought out to be seen only from time to time. This occasional viewing has everything to do with format.

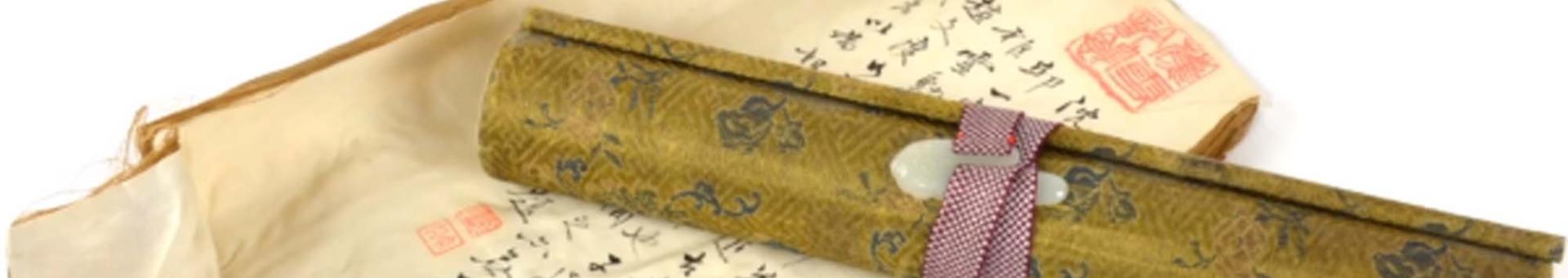

Ceremony and anticipation underlie the experience of looking at a handscroll. When in storage, the painting itself is several layers removed from immediate view, and the value of a scroll is reflected in part by its packaging. Scrolls are generally kept in individual wooden boxes that bear an identifying label. Removing the lid, the viewer may find the scroll wrapped in a piece of silk, and, on unwrapping the silk, encounters the handscroll bound with a silken cord that is held in place with a jade or ivory toggle. After undoing the cord, one begins the careful process of unrolling the scroll from right to left, pausing to admire and study it, shoulder-width section by section, rerolling a section before proceeding to the next one.

The experience of seeing a scroll for the first time is like a revelation. As one unrolls the scroll, one has no idea what is coming next: each section presents a new surprise. Looking at a handscroll that one has seen before is like visiting an old friend whom one has not seen for a while. One remembers the general appearance, the general outlines, of the image, but not the details. In unrolling the scroll, one greets a remembered image with pleasure, but it is a pleasure that is enhanced at each viewing by the discovery of details that one has either forgotten or never noticed before.

Looking at a handscroll is an intimate experience. Its size and format preclude a large audience; viewers are usually limited to one or two. Unlike the viewer of Western painting, who maintains a certain distance from the image, the viewer of a handscroll has direct physical contact with the object, rolling and unrolling the scroll at his/her own desired pace, lingering over some passages, moving quickly through others.

As the scroll unfurls, so the narrative or journey progresses. In this way, looking at a handscroll is like reading a book: just as one turns from page to page, not knowing what to expect, one proceeds from section to section; in both painting and book, there is a beginning and an end.

Indeed, this resemblance is not incidental. The handscroll format—as well as other Chinese painting formats—reveals an intimacy between word and image. Many handscrolls contain inscriptions preceding or following the image: poems composed by the painter or others that enhance the meaning of the image, or a few written lines that convey the circumstances of its creation.

Many handscrolls also contain colophons, or commentaries written onto additional sheets of paper or silk that follows the image itself. These may be comments written by friends of the artist or the collector; they may have been written by viewers from later generations. The colophons may note the quality of the painting, express the rhapsody (rarely the disenchantment) of the viewer, give a biographical sketch of the artist, place the painting within an art-historical context, or engage with the texts of earlier colophons. And as a final way of making their presence known, the painter, the collectors, the one-time viewers often “sign” the image or colophons with personal seals bearing their names, these red marks of varying size conveying pride of authorship or ownership.

This long handscroll work is an imaginary representation of various activities in a Han dynasty (206 BC–AD 220) palace on a spring morning. Among them is the famous story of Mao Yanshou painting the portrait of Wang Zhaojun. As the story goes, the concubines of Emperor Yuandi (r. 48–33 BC) were so numerous that he ordered the artist Mao Yanshou to paint their portraits in order to choose them for attendance. Except for the righteous Wang Zhaojun, all the concubines bribed the artist to portray them even more beautiful. For not receiving a bribe, the artist portrayed Wang less beautiful, ruining her chances of seeing the emperor. One day, when a barbarian chieftain came to the court seeking relations, he sought a Han beauty as his wife. The emperor, believing Wang Zhaojun to be the least attractive of the concubines, chose her as the chieftain’s wife. Only when he saw her did he realise that she was the most beautiful of them all. Infuriated, he had the artist executed.

Thus, the handscroll is both painted image and documentary history; past and present are in continuous dialogue. Looking at a scroll with colophons and inscriptions, a viewer sees not only a pictorial representation but witnesses the history of the painting as it is passed down from generation to generation.

TouTube links

Screenshot, YouTube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q3Ut32EZgpg&feature=youtu.be

Screenshot from YouTube ‘Viewing a Handscroll’ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8xE7DVa4p60

Illustrations

Wu Zhen, Fisherman, ca. 1350, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public Domain

Spring Morning in the Han Palace, (detail) 17th cent copy after Qiu-ying, (Ming Dynasty,1368-1644), Walters Art Museum, CC0 (no rights reserved)

by Jeni Fraser

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

Dear Arts Society Member

Welcome to our February newsletter.

During the winter months a small group of Bibliophile volunteers from the Bowdon Arts Society meet on Thursday mornin