This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

Leonardo's Masterworks

Leonardo's Masterworks

2 May 2019

To mark the 500th anniversary of Leonardo da Vinci’s death, a new exhibition at The Queen’s Gallery, Buckingham Palace will show more than 200 of his drawings. Curator Martin Clayton reveals some of the highlights.

SEEK THE SURPRISE

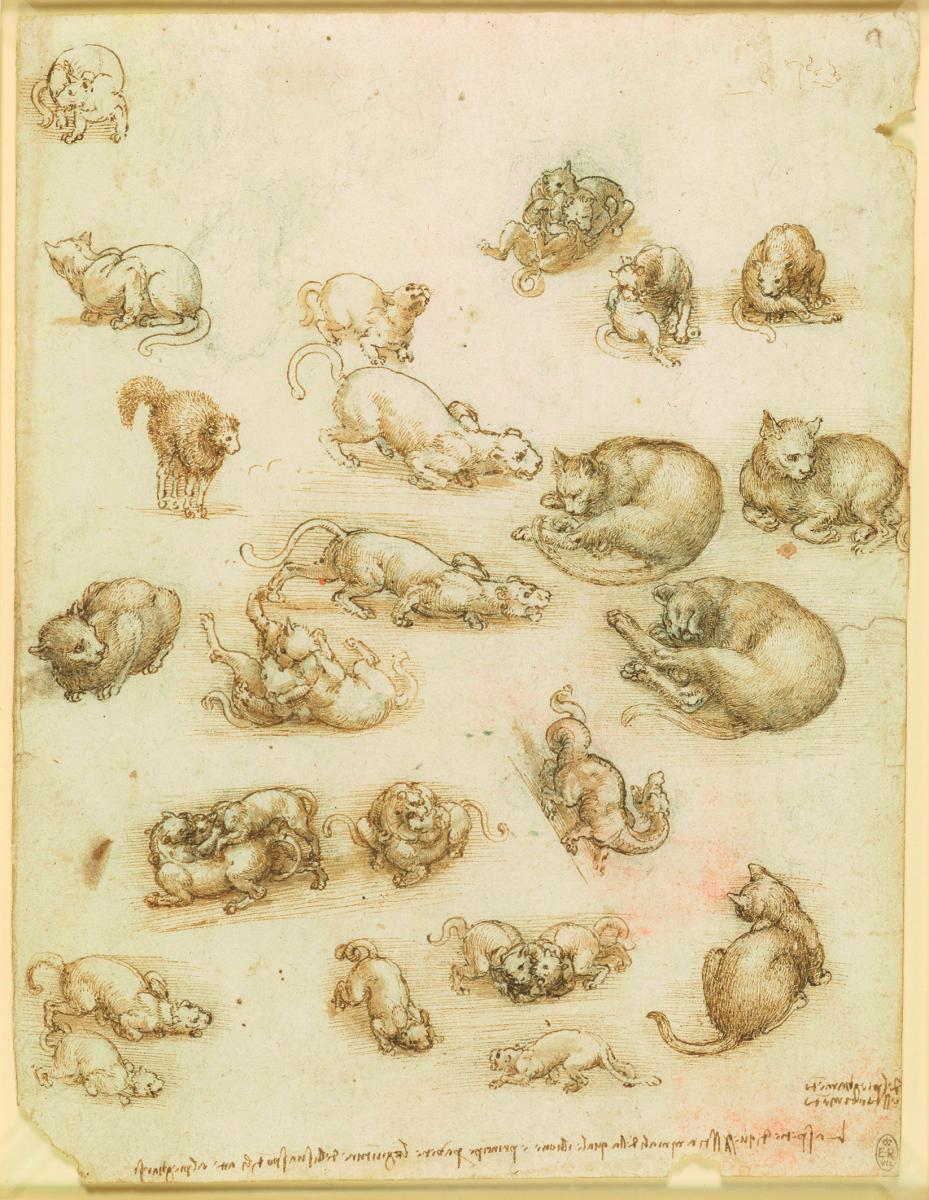

Cats, Lions and a Dragon, c1517-18, Black Chalk, Pen and Ink, Wash

Cats, Lions and a Dragon, c1517-18, Black Chalk, Pen and Ink, Wash

Drawn with care and attention, this work contains more than 20 cats and lions. Leonardo believed that these animals had the most flexible spines of any species in the natural world. He thought that by rendering them in different positions, it would help him to understand the principles of animal motion. This sheet is an example of Leonardo thinking aloud: he’s drawing ideas on paper to form the basis of further investigations. It contains an interesting surprise too. Tucked among the domestic and wild cats is a little dragon.

BOTANICAL WONDERS

A Star-of-Bethlehem and Other Plants, c1506-12. Red Chalk, Pen and Ink

This drawing features a clump of star of Bethlehem, wood anemone and sun spurge – plants that Leonardo would have come across in woodlands. He is trying to capture

the life and vivacity of the star of Bethlehem, depicting its movements and internal growth forces. To capture the intricacies of the plant, Leonardo uses pen, ink and red chalk – a material that gives a rich, dense mark when cut to a point. Suggestive of fertility and abundant growth, these plants were used as studies for his painting Leda and the Swan.

DESTROYED MASTERPIECE

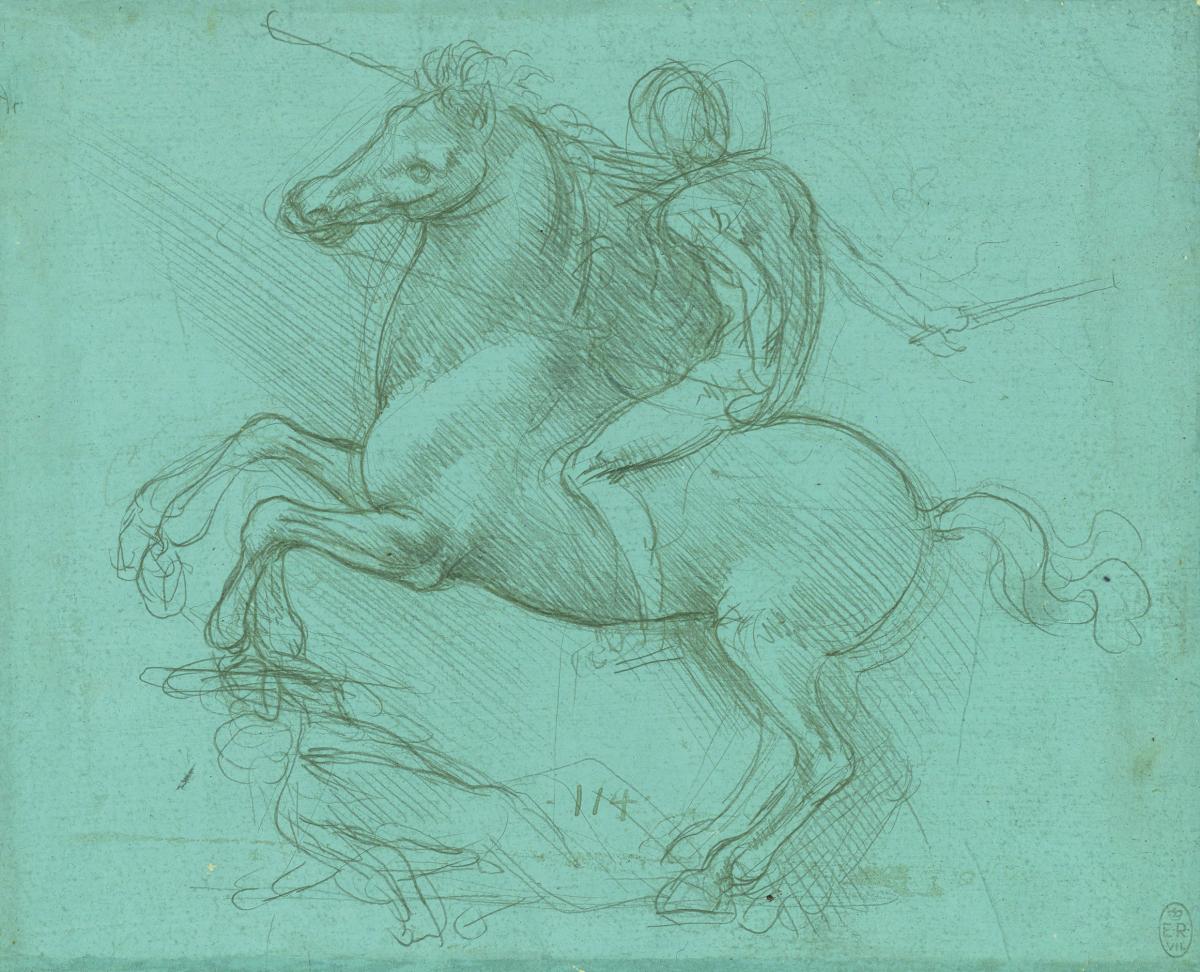

A Design for an Equestrian Monument, c1485-8. Metalpoint on Blue Prepared Paper

A Design for an Equestrian Monument, c1485-8. Metalpoint on Blue Prepared Paper

This design is all that remains of one of Leonardo’s most ambitious works. During the 1480s, Ludovico Sforza, the ruler of Milan, commissioned Leonardo to create a bronze equestrian monument, in honour of his father. Leonardo spent almost 10 years working on the project, making a full-scale clay model for the sculpture, and building a foundry to assemble the bronze. But the masterpiece was never completed. In 1494, the bronze was requisitioned to make cannon. Five years later, when French forces invaded Milan, the troops used Leonardo’s clay model for target practice. His masterpiece was destroyed before his eyes.

CHARTING THE LANDSCAPE

A Map of the Valdichiana, c1503-6. Black Chalk, Pen and Ink, Wash, Blue Bodycolour

A Map of the Valdichiana, c1503-6. Black Chalk, Pen and Ink, Wash, Blue Bodycolour

The Florentine government commissioned Leonardo to work on civilian and military engineering projects, including this map of the Valdichiana in southern Tuscany. It is likely that Leonardo was commissioned to survey this marshy region, with the idea of draining it. Among the area’s rolling hills, major cities, including Siena and Perugia, can be seen. This drawing is based on pre-existing maps of the area, and was made with materials including black chalk, ink and blue bodycolour (watercolour mixed with pigment).

ANCIENT MYTH

The Head of Leda, c1505-8. Black Chalk, Pen and Ink

The Head of Leda, c1505-8. Black Chalk, Pen and Ink

Drawing upon themes of procreation and the fecundity of nature, this drawing of a woman’s head was a study for Leonardo’s lost work Leda and the Swan. According to mythology, Jupiter, the king of the gods, transformed into a swan and seduced Leda, queen of Sparta. This is the only female nude Leonardo ever painted, and it highlights his love of personal decoration. Far from drawing a seductive female nude, Leonardo has drawn Leda with a conventional expression, her eyes cast demurely downwards. Instead, he devotes his energy to her elaborate hairstyle, with intricately knotted plaits.

MINIATURE SKULL

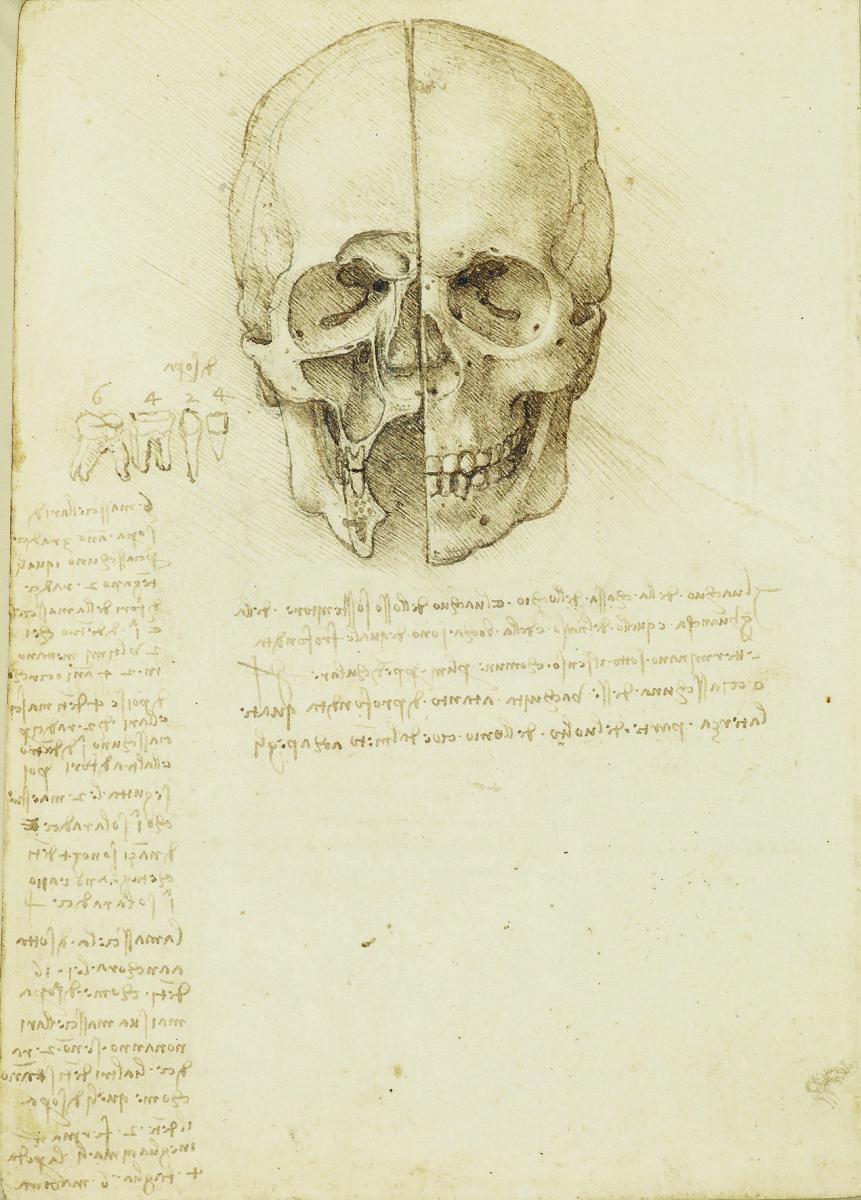

The Skull Sectioned, 1489, Traces of Black Chalk, Pen and Ink

The Skull Sectioned, 1489, Traces of Black Chalk, Pen and Ink

Bringing together scientific objectivity and exquisite artistry, Leonardo’s drawing of a sectioned skull is one of the earliest of his anatomical drawings. Unlike other anatomists of the era, Leonardo was interested in trying to understand how the shape of a bodily part, and its function, are intimately connected. No more than three inches high, this tiny drawing explores the relationship between the skull’s cavities and its surface features. The work also shows Leonardo’s ‘mirror writing’ – a style that moves from the right to the left of the page. In the text, he describes the skull’s nerve passageways and the form and number of the teeth.

ALL IMAGES: ROYAL COLLECTION TRUST/© HER MAJESTY QUEEN ELIZABETH II 2019

SEE

Royal Collection Trust has collaborated with 12 museums and galleries across the UK to stage exhibitions of Leonardo’s work; on until 6 May.

Leonardo da Vinci: A Life in Drawing, 24 May–13 October, The Queen’s Gallery,

Buckingham Palace, London;

bothrct.uk/leonardo500

About the Author

The Arts Society

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition