Tattoos as fine art: Q&A with Dr Matt Lodder

Tattoos as fine art: Q&A with Dr Matt Lodder

26 Jun 2018 - 11:14 BY The Arts Society

- Featured lecturer

Arts Society Lecturer Dr Matt Lodder takes us under the skin of tattooing’s rich history.

Dr Matt Lodder

Tattoos are no longer taboo. As a society, we’ve never been more inked: it’s thought that as many as one in five British adults sports a tattoo.

But it would be a mistake to think that we’re living through the first moment in time when fashion and culture has embraced ink. As an art form, its history is wide-reaching and incredibly rich, as Arts Society Lecturer and art historian Dr Matt Lodder can tell us. He has spent his career looking at Western tattooing from the 17th century to the present day – with all its romance, mystery and a great many surprises.

He tells us a little more about his work…

How did your interest in tattoos begin?

I was told two cautionary tales as a child. The first was of my great-grandmother, who had been tattooed around 1900, when her brothers arrived home one day with a tattoo machine. She agreed to let them tattoo her on the understanding that it would wash off. Of course, it didn’t – and so she was burdened with her initials permanently etched into her wrist for the rest of her life.

The second was of my grandfather, who woke up in a tattooist’s chair in Jakarta in the 1940s as they were about to tattoo a fly on the end of his nose. He had a lucky escape! Those two stories told together were supposed to warn me off tattooing for life, but they sparked a lifelong fascination and a wonderfully exciting career.

When – and how – did you realise that it was a subject you could pursue in an academic career?

My route into a PhD is a fairly well-worn one – when I was a student, I kept looking for answers in existing books to the questions I had about the things which interested me, and simply didn’t find them. So I knew I’d have to write them myself!

From an art historical perspective, what are the key moments in the history of tattoos?

These aren’t perhaps the ‘key moments’ for the story as a whole, but I think the moments where tattooing and a more conventional art history meet might be of interest in this context. For example, some of the best and most extensive representations of maritime tattooing in painting are actually in a pair of enormous wall murals in the Palace of Westminster, painted by Daniel Maclise in 1862. The murals are next to the main chamber of the House of Lords, and commemorate the battles of Waterloo and Trafalgar; they feature numerous intricately tattooed sailors.

I’m also delighted to find examples in my research of people who have copies of their favourite paintings tattooed on them. There are some remarkable copies of William Bougerau salon paintings tattooed in the late 19th century, and also several notable instances of popular Japanese prints, such as those by Hokusai, which indicate an Orientalist craze at the very beginning of the professional tattoo industry in this country.

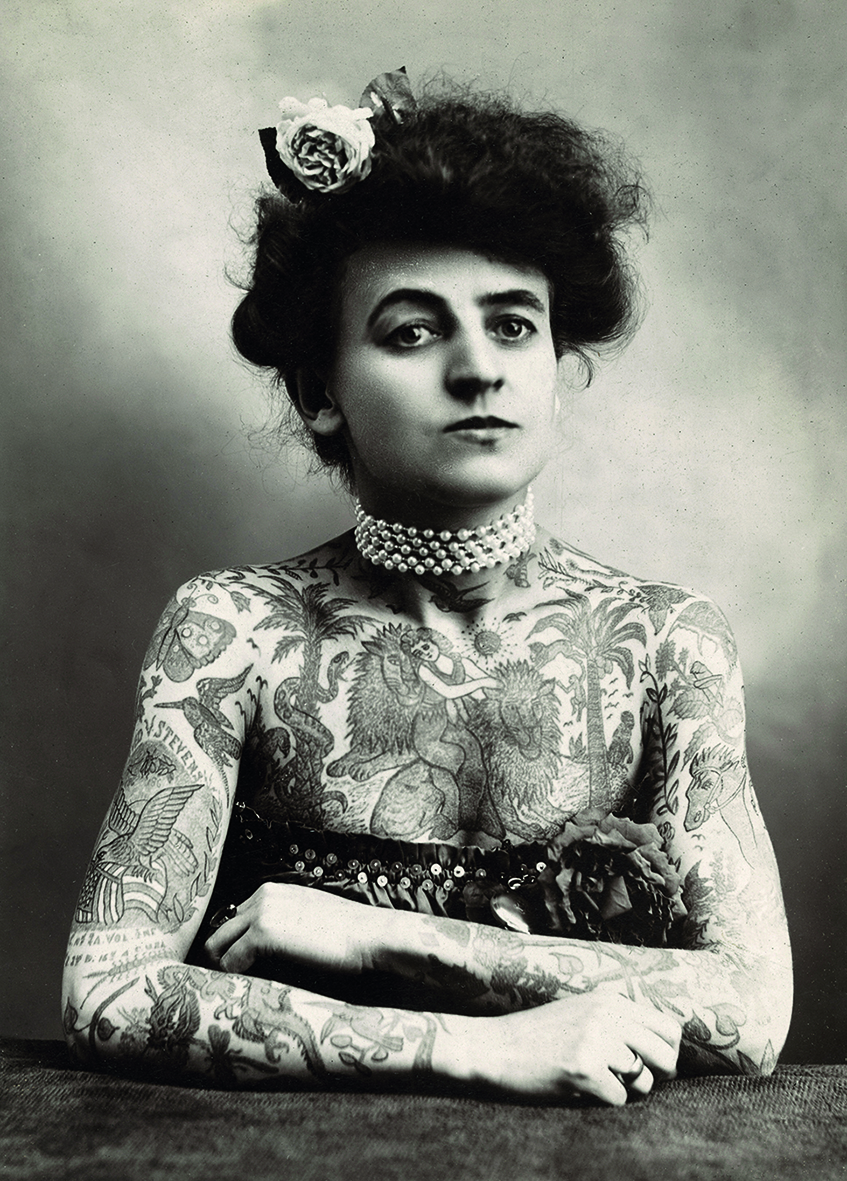

Maud Wagner (1877–1961), an American circus performer and the first known female tattoo artist in the US, c.1911 Credit: Granger/Bridgeman Images

You have recently curated an exhibition on tattoos, Tattoo: British Tattoo Art Revealed, at the National Maritime Museum in Falmouth. What were your top three items on display and why?

Most important for the history of tattooing in this country, perhaps, was an enormous hand-painted banner used by a dockside tattoo artist around World War I. The banner is unique, and covered in delicately rendered tattoo designs in oil paint on a canvas sheet. It had some almost mythical status in the tattoo industry, and had long been thought lost, until I discovered it as part of an extensive and unseen private collection in Wales, hidden away in a loft.

Another highlight included a 3D printed replica of a 17th-century tattoo stamp from the Middle East, used to lay out designs on the arms of pilgrims.

I must also mention the preserved tattooed human skins that we borrowed from the Wellcome Collection in London, which had been acquired in France in 1924. The skins preserve the tattoos of prisoners and soldiers from French campaigns in North Africa; we were delighted to be able to include one which was in two parts, an eyeball tattooed on each. It turns out that these were buttocks, and the eyeball tattoos a fairly common gag tattoo!

What, for you, has been the most unusual tattoo you have come across in your research?

One soldier during World War I was hit with some shrapnel in his ankle – his tattooist revealed that the existing tattoos he had, which resembled socks, had to be ‘darned’ to fix! There are numerous examples of men getting portraits of Edward VII and George V tattooed on their bald spots, around the times of their coronations.

One member of the House of Lords had a full back tattoo of a fox hunt, with the fox escaping safely rather theatrically down its hole! Rather salacious tattooing of this kind also has a long and storied history!

Why do you think that tattoos, as a body art form, have had such a surge in popularity in recent years?

In 1926, a journalist for Vanity Fair wrote that tattooing had ‘passed from the savage to the sailor, and from the sailor to the landsman, and is now to be found beneath many a tailored shirt’. I have examples of similar headlines – telling us that tattooing is the hot new trend! – from every decade since the 1880s. A lot of my writing and exhibition-making is focused, therefore, on trying to break the myth that tattooing is a particularly novel activity on these shores, but is instead an integral part of our cultural life.

Dr Matt Lodder offers multiple lectures on his chosen subject, from The Untold History of Tattooing to Tattooing and The Great War.

He is a lecturer in Contemporary Art and director of American Studies in the School of Philosophy and Art History at the University of Essex.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

BECOME A LECTURER

The Arts Society has a directory of speakers and we are always interested to hear from enthusiastic, knowledgeable and entertaining lecturers who speak about the arts.