Dear Arts Society Member

Welcome to our February newsletter.

19 Sep 2020

Viva Rivera! by Jeni Fraser

In the early 1920s in Mexico the government commissioned artists to make art that would educate the mostly illiterate population about the country’s history and present a powerful vision of its future. Inspired by the idealism of the Revolution, artists created epic, politically charged public murals that stressed Mexico’s pre-colonial history and culture and that depicted peasants, workers, and people of mixed Indian-European heritage as the heroes who would forge its future. Out of a host of Mexican artists, Diego Rivera (1886–1957), emerged as its most devoted, celebrated, and prolific proponent*.

Rivera – probably better known as the husband of Frida Kahlo - had visited Italy to study Renaissance frescoes, a mural form recognised as a valuable medium of education and inspiration. Returning to Mexico in 1921, Rivera began a remarkable series of frescoes—paintings made on moist plaster, so that the pigments fuse with the plaster as it dries. The mural was monumental in scale and painted on three adjoining walls of the National Palace, overlooking the imposing colonial building’s main staircase. Riviera subdivided the overall them in relation to the architectural disposition of the walls – the largest, the central one, displays the part of Mexican history that Rivera regarded as more widely and objectively known, namely the period from the Spanish conquest of Mexico in 1519 up until and including the Revolution. On the two adjoining walls, Rivera painted other periods of Mexican history – on the right, the pre-Columbian world while on the left, a panorama of modern-day Mexico, as he saw it.

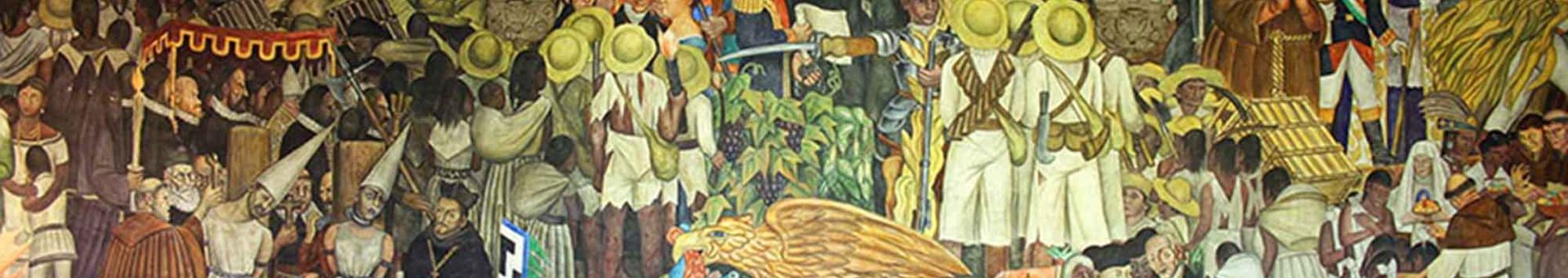

The central panel contains a complex of figures identified with centuries of struggle and resistance to colonial subjugation and dictatorship in an ascending chronology. At the very centre lies the Aztec symbols of an eagle with a serpent in its mouth – Rivera’s symbolic national heart. At the bottom, Cuauhtémoc (the last Aztec prince who ruled Tenochtitlan from 1520-1521) in combat with the conquistador Cortez references the first struggle against the outsider. The Aztec’s portrayal also symbolises disbelief in the myths and superstitions that mistakenly lead Aztec priest to believe that Cortez represented the returning incarnation of their god Quetzalcoatl, a belief that in no small way facilitated the conquest of the Aztec kingdom.

In the sequences above, Rivera isolates other significant moments of resistance and heroism in the prominent images of the priests Dom Miguel Hidalgo (1753-1811, behind the sword) and José Maria Morelos (1765 – 1815, wearing a white cap and pointing to his left), the father figures of Mexican independence in the 19th century. Above them, at the apex of the central arch and acting as a thematic and ideological ‘crown’ to the whole cycle are Alvaro Obregón (1880-1928) and his successor Plutarco Elias Calles (1877-1945), (who stand together wearing ‘business’ suits), the political leaders of the revolution and its aftermath. Carrillo Puerto (1874-1924) the Indian socialist governor of Yucatán, Francisco (“Pancho”) Villa (1878 – 1923) and Luis Cabrera (18756-1954), the lawyer and author, are also portrayed, standing behind the famous standard of the revolution, with its words Tierra y Libertad (land and freedom).

The secondary vertical tiers of the composition - under the two arches on either side of the centre - contain scenes representing the positive and negative aspects of the great political struggles of the 19th and early 20th centuries in ‘conversation’. For example: the introduction of Catholicism depicted on the right-hand side transforms the superstitious spirituality of the Indians and their nature gods, while on the left the cruel arm of this religious conversion is pictured in images of the Spanish Inquisition, juxtaposed with images of the branding and slavery of Indians. Similarly, the two side panels comment on the Mexican-American war of 1847 (right side) , the French occupation of Mexico in 1861, and the rule of the puppet Austrian emperor Maximilian (whose execution was painted by Manet), on the left. Together with these images of conquest and dictatorship – and the heroic tradition of resistance – Rivera shows the struggle taking place in a country whose people have been totally and irrevocably transformed by three centuries of colonial rule.

In a surprising addition to this line-up we find, in the left-hand, panel, an image of Karl Marx. Rivera was an avowed Communist, and in picturing the revolutionary struggles of the workers’ movements together with the portrait of Marx, Rivera presents contemporary political struggles as part of the national heritage. Rivera was forced to depict Marx and the world he proclaimed as a golden age to which Mexico would return, mirroring Quetzalcoatl, the Aztec god of life, light, and wisdom, painted on the opposite wall. Yet, as with the great Aztec kingdom, the Marxist domain kay beyond any real experience to which Rivera could be a witness. He could therefore do nothing but paint it as a utopia.

As with much history painting, Rivera’s mural renders into the realm of myth every event and every personage connected to the nation’s history. Perhaps, post-pandemic, a visit to Mexico City could feature on your ‘bucket list’ – you’d be amply rewarded if you visited.

Illustration: Diego Rivera - La historia de México- de la conquista al futuro, (detail) 1929-1935. Mural at Palacio Nacional, Ciudad de México

See also José Clemente Orozco and David Alfaro Sisquieros

Jeni Fraser

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

Dear Arts Society Member

Welcome to our February newsletter.

During the winter months a small group of Bibliophile volunteers from the Bowdon Arts Society meet on Thursday mornin