This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

The star artists of the Little Ice Age

The star artists of the Little Ice Age

18 Jan 2024

When the Little Ice Age hit the northern hemisphere from the early 14th century it had artists reaching for their brushes in response to the frosty phenomenon. Clare Ford-Wille revels in the frosty results

Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s Massacre of the Innocents, c.1565–67. Image: Google Art Project

Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s Massacre of the Innocents, c.1565–67. Image: Google Art Project

There are mysteries about the Little Ice Age.

Historians cannot agree the exact timing of its beginning, nor why it lasted well into the 19th century. Records such as diaries and letters exist but are patchy and not scientifically rigorous. Yet there is consensus that the Little Ice Age began sometime around 1300 and lasted until the 1870s.

Above all, there is agreement that climate changes bringing extreme periods of cold occurred in the 16th century and lasted throughout the 17th century.

This extraordinary phenomenon prompted Flemish and Dutch artists’ exploration of the art of winter landscape, which became a very special contribution to the history of art.

Among the remarkable works to emerge was Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s Hunters in the Snow, painted following the extreme winter of 1565 as part of a series, the Seasons, for the Antwerp banker and art collector Nicolaes Jonghelinck.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s Hunters in the Snow. Image: Google Art Project

Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s Hunters in the Snow. Image: Google Art Project

It has been suggested that this is the ‘first winter scene in art’, but that is not quite true.

Bruegel was following, on a new, larger format, on wooden panel, a tradition: that of paintings and sculptures of the seasons relating human activity to the unfolding of the Christian year.

This was sometimes combined with the signs of the zodiac decorating illuminated pages of books of hours; we see this in the early 15th-century Très Riches Heures by the Brothers Limbourg.

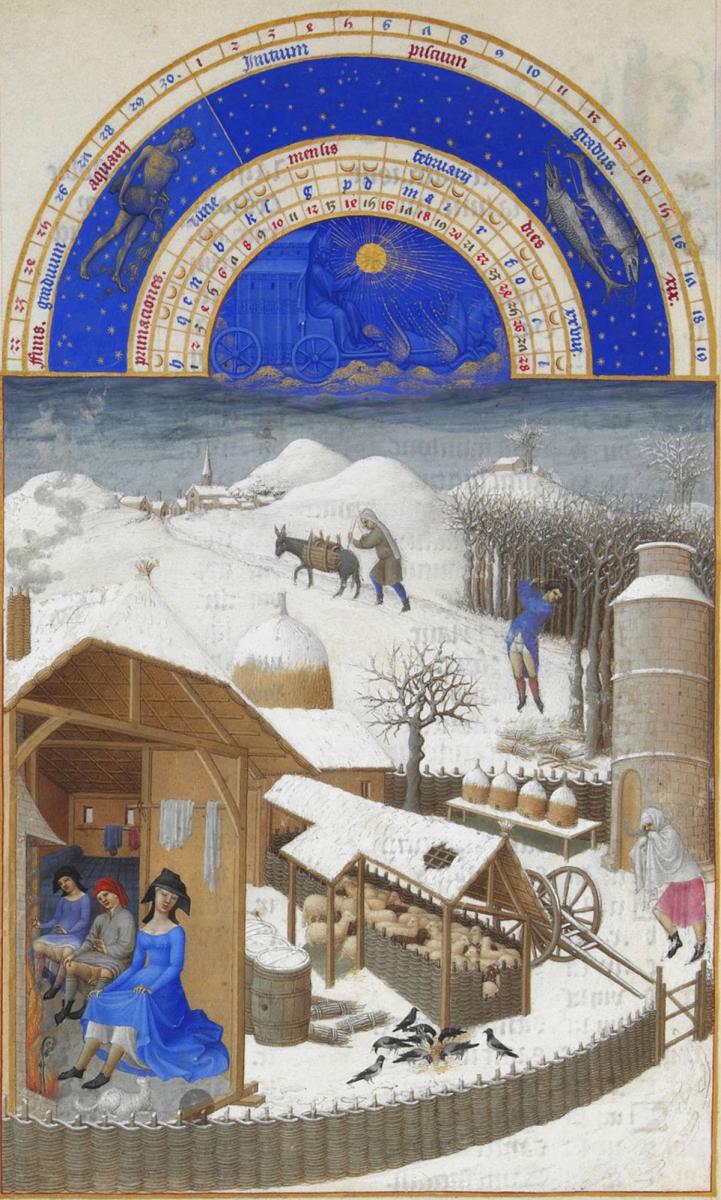

Très Riches Heures, Février. Image: Wikimedia Commons/RMN/R-G OJEDA

Très Riches Heures, Février. Image: Wikimedia Commons/RMN/R-G OJEDA

What is remarkable about the small ‘February’ illumination in Très Riches Heures is the deep snow and the busy winter activities of the peasants. Peer closely and you’ll see them fetching firewood and keeping the animals safely together for warmth in an enclosure. Little else could be achieved in such arctic conditions, except to sit near a fire lifting skirts and tunics for maximum warmth. What is exceptional about this illustration is the observation of the leaden wintry sky, and the effect of mist created by warm breath expelled from the peasant’s mouth as he checks the farmstead before night falls.

No other convincing winter scenes survive from the remainder of the 15th century, and they remained few until the increasingly severe winters of the later years of the 16th century.

This was when Pieter Bruegel’s scene spurred a tradition of larger paintings of wintry views – a movement continued by his family, especially Pieter Brueghel the Younger, and artists in the Southern Netherlands.

In the following century the genre of painting icy scenes swiftly spread to the Dutch provinces, through wonderful work by artists such as Hendrick Avercamp.

A Scene on the Ice near a Town, 1615, by Hendrick Avercamp. Image: Wikimedia Commons

A Scene on the Ice near a Town, 1615, by Hendrick Avercamp. Image: Wikimedia Commons

Such scenes involved landscape painting.

This medium emerged at the start of the 16th century in the work of Flemish painters, when the power of the Catholic Church was weakening. Religious subject matter diminished as Protestantism grew, with the consequent prohibition of elaborate Christian art. Views of landscape, everyday life and still life made new and powerful subjects.

They often had a symbolic and moralising function, suggesting the importance of the transitory nature of life. In addition, the Spanish-ruled Netherlands separated at the end of the 16th century. This provided another catalyst: now the cities and towns of the Netherlands came to be composed of a growing, wealthy middle-class mercantile society with spending power.

They were the collectors of art, with an enthusiasm for all things new.

The fresh wave of paintings of icy landscapes became a ‘must have’ at this time of extreme cold and frost.

It was against this backdrop that Pieter Bruegel the Elder would create masterpieces such as Hunters in the Snow. Just one of the exceptional elements of such works is how every figure within them was equally vulnerable against the threatening freeze of winter, whether rich or poor.

In Hunters in the Snow figures play joyfully on the ice in the middle ground contrasting, in the foreground, with the tired hunters and their dogs, bent against the cold wind, having little to show after their long day in the snow. In the far distance, we can see one of the first representations of the Alps, the mountains looming over the valley against a bleak sky.

Bruegel’s The Adoration of the Magi in the Snow. Image: Wikipedia Commons

Bruegel’s The Adoration of the Magi in the Snow. Image: Wikipedia Commons

Bruegel was also possibly the first artist to begin to set important historical and religious events in the season of winter. See his Massacre of the Innocents (top) or The Census at Bethlehem. This act of taking famed scenes and giving them a wintry twist has been followed ever since.

The equalising, frightening effects of winter weather can be seen powerfully in Bruegel’s tiny Adoration of the Magi in a Winter Landscape or in the Snow (above), where the depiction of a snowstorm is so convincing that it seems to overcome the Magi, their retinue and the Holy Family in the simple Flemish village in which the event is set.

Towards the close of the 16th century, when those Protestant Flemish artists were fleeing the Southern Netherlands and the rigorous control of the Spanish to seek refuge in the northern Dutch provinces, they took those new landscape ideas with them.

Hendrick Avercamp, who was born in Amsterdam in 1585, was to be a worthy successor to Pieter Bruegel, transforming the subject into immediately recognisable frozen expanses peopled with every layer of society, enjoying or suffering from the icy experience in myriad ways.

A Winter’s Scene with Skaters near a Castle, Hendrick Avercamp. Image: Wikipedia Commons

A Winter’s Scene with Skaters near a Castle, Hendrick Avercamp. Image: Wikipedia Commons

His earliest dated A Winter’s Scene with Skaters near a Castle (1608) was painted following another hard winter.

It is thought Avercamp was a deaf mute, which may have contributed to his powers of observation, not only of the sheer variety of people and activities on the ice, but also to his treatment of the leaden wintry skies with hints of pink in the clouds, as in his A Scene on the Ice near a Town (1615).

No other 17th-century artist specialised in winter landscape quite like Avercamp, although other Dutch artists included the subject in their careers, such as Esaias van de Velde, Jan van Goyen, Arent Arentsz and Abraham Hondius.

The Frozen Thames, 1677, by Abraham Hondius. Image: © Museum of London/Heritage Image Partnership Ltd/Alamy Stock Photo

The Frozen Thames, 1677, by Abraham Hondius. Image: © Museum of London/Heritage Image Partnership Ltd/Alamy Stock Photo

Hondius travelled to London and painted the famous frost fairs on the Thames in works such as The Frozen Thames(1677) and A Frost Fair on the Thames at Temple Stairs (1684).

The frost on the Thames of 1683–84 was the most extreme known in London. ‘I went across the Thames on the ice, now become so thick as to bear not only streets of booths … but coaches, carts, and horses …’ wrote the famed London writer John Evelyn in 1684. Among the populace the Thames became known as Freezeland Street.

Later, in the early 19th century, after two of the most extreme winters on record in 1812 and 1816 (called the ‘year without a summer’), great artists such as Caspar David Friedrich and Claude Monet would respond once again to the wonders of the Little Ice Age.

The ‘new’ sensational art of winter had firmly earned its icy place in the history of art.

About the Author

Clare Ford-Wille

is an art historian and Arts Society Accredited Lecturer

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition