This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

My life in art: Arts Society Lecturer Susan Whitfield

My life in art: Arts Society Lecturer Susan Whitfield

22 Oct 2019

Susan Whitfield specialises in the historiography of Chinese Central Asia, specifically the Silk Road (which she has travelled on numerous occasions). She holds an honorary position at the University College London Institute of Archaeology and worked as curator of the Central Asia manuscript collection at the British Library for 25 years.

The story of Sukhra’s defeat of the Hephthalites, illustrated here in a 16th-century manuscript. Image credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The story of Sukhra’s defeat of the Hephthalites, illustrated here in a 16th-century manuscript. Image credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Your new book, Silk Roads, is about to be published. Why is it a particularly important time to bring together scholarship on this subject?

With a mutable world order and increased questioning of the effects of immigration and diversity, I believe it is more important than ever to explore the interactions of the peoples, arts and cultures of Afro-Eurasia in the pre-modern world. In this book I have also sought to represent the whole geographical and cultural range covered by the Silk Roads, including often-neglected cultures. For example, the Red Sea kingdoms of Axum and Himyar, in today’s Ethiopia, Eritrea and Yemen, were rich cultures with a significant role in Silk Road history. We can all too easily forget this past when we are only presented with images of poverty and conflict.

A Child’s silk coat. The two materials of the outer part and lining used in this child’s coat, which was found with a pair of trousers, reflect the exchange and blending of silk cultures along the Silk Road. Image credit: Cleveland Museum of Art

A Child’s silk coat. The two materials of the outer part and lining used in this child’s coat, which was found with a pair of trousers, reflect the exchange and blending of silk cultures along the Silk Road. Image credit: Cleveland Museum of Art

You gained a PhD in Chinese Historiography. How do you define the term, and why it is such a vital area of study?

An understanding of the past is vital to assessing and questioning the legitimacy and effects of events in the present. Political regimes throughout history have sought to control this by providing their own historical narratives to give their regimes legitimacy and by restricting access to alternative views. The various regimes ruling China up to the present are no exception. This is seen in the spurious Silk Road narratives of the Belt and Road Initiative and, most recently, in the story of China post-1949 presented by the Communist Party in its 70th-anniversary events. It is vital that everyone has access to alternative narratives and learns the skills to question and judge between them.

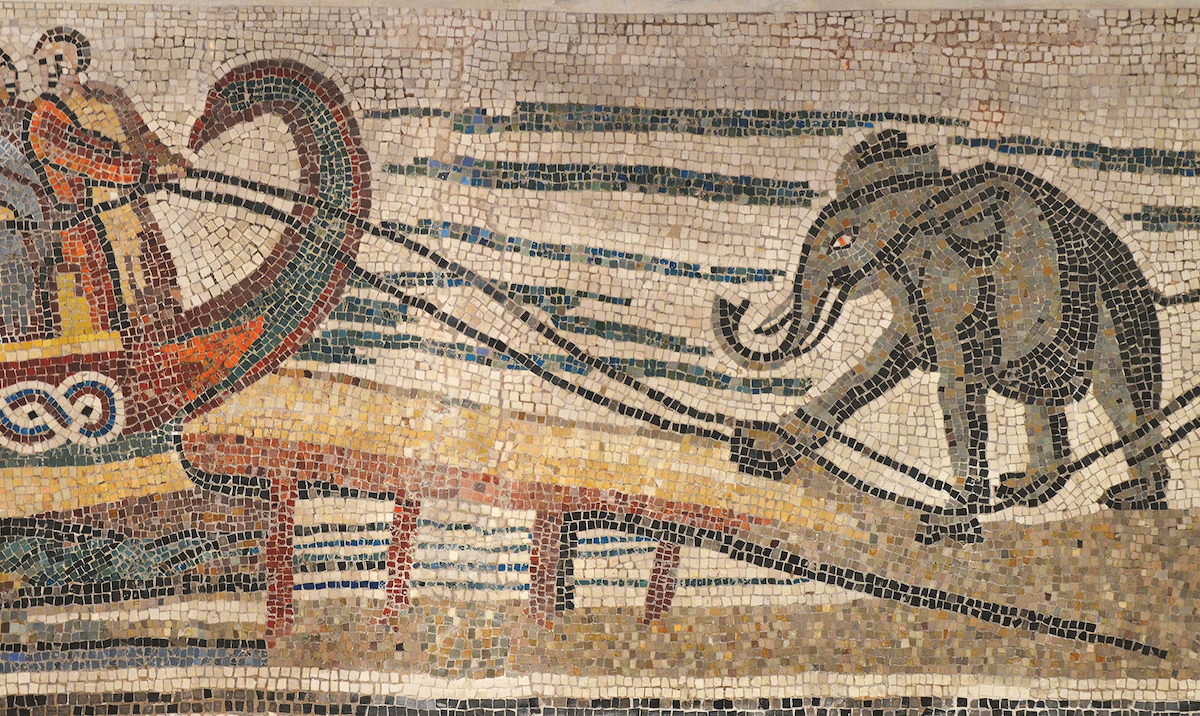

Sea transport was more efficient and cheaper for large, heavy and fragile cargo, including metals, glass, ceramics, slaves and, as shown in this 3rd- to 4th- century Roman mosaic from Veii, animals such as elephants. Image credit: Badisches Landesmuseum Karlsruhe

Sea transport was more efficient and cheaper for large, heavy and fragile cargo, including metals, glass, ceramics, slaves and, as shown in this 3rd- to 4th- century Roman mosaic from Veii, animals such as elephants. Image credit: Badisches Landesmuseum Karlsruhe

When and how did your fascination with the ancient Silk Road trading routes first come about?

As a student of medieval China, I struggled to understand the richness and diversity of the arts and cultures within the historiographical framework presented by my teachers and by many writers – that of a culture and history of a homogenous China. It was the realisation that China is much more like Europe – diverse peoples, cultures and arts as a result of migration, invasion and trade – that helped me start to gain more understanding. In the medieval period, much of China’s diversity came through what is now termed the ‘Silk Roads’ and once I started exploring this I was drawn in by the complexity of its interactions.

Could you tell our readers about one significant and fascinating object that is featured in your book?

The female polo-player shown here is a favourite piece of mine. The horse was introduced to China from the steppe centuries before the Silk Road. The armies of China started using cavalry to match the mobility of their steppe neighbours in warfare. But during the Silk Road period the horse became part of elite as well as military life in China, with envoys sent to seek fine horses from the Ferghana Valley and elsewhere in central Asia. The imperial stables in Xian held strings of hunting mounts and polo ponies. Visiting envoys were taken on hunts or challenged to polo matches. By the 7th and 8th centuries, the fashion among elite men and women was the so-called ‘foreigners’ dress’, comprising baggy trousers and a short split-sided tunic, suitable for horse riding.

What first compelled you to become an Arts Society Lecturer?

I feel privileged to have had the opportunities to study the Silk Road, to travel to many ancient sites, meet scholars worldwide and, above all else, work closely with texts and artefacts from across its length. The Silk Road has so many interesting stories to tell and I wanted to share these, not only with fellow academics. The Arts Society’s well-informed and enthusiastic audiences spread throughout the UK — and abroad — seemed like an ideal opportunity, not least because they often ask questions or share experiences that make me re-evaluate my own knowledge.

BUY

Silk Roads: Peoples, Cultures, Landscapes, edited by Susan Whitfield

Published by Thames & Hudson

About the Author

The Arts Society

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition