This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

Light on Egypt

Light on Egypt

24 Aug 2022

An upcoming show at the Sainsbury Centre is set to unpick art’s constructed fantasies of ancient Egypt. We ask curators Dr Benjamin Hinson and Dr Anna Ferrari for the story

Artists have looked to Egypt for centuries: from antiquity, through to the Cleopatra of Shakespeare’s stage and Shelley’s Ozymandias to today, with figures like David Hockney and Awol Erizku reinterpreting Egyptian imagery and themes. This fascination with ancient Egypt is not a neutral phenomenon – it has often reflected underlying political motivations.

Now, in Visions of Ancient Egypt, we explore for the first time this enduring legacy, bringing the story – and issues surrounding it – to the present day. Ancient Egypt has proven endlessly inspirational. Unlike other ancient cultures, it never truly ‘died’; echoes remained through religious stories and the accounts of classical authors. The name ‘Egypt’ was always present in Western culture, even if it conjured an imagined vision. Indeed, ideas of ancient Egypt have proven highly mutable, and have been exploited to suit different agendas. Egypt can act as a cypher for wisdom and law; the arcane, mysterious and esoteric; monumentality and permanence; or the sublime and ideas of death. There is no ‘one’ Egypt.

‘EACH TIME EGYPT APPEARS IN ART, IT TELLS US SOMETHING ABOUT THOSE REUSING IT’

Just as the meanings of Egypt are flexible, so too is the imagery in art. Until the 19th century few had travelled there. Most direct encounters with Egyptian art came through pieces seen in Rome, and Egypt was understood through a classical lens. The same key objects appeared in art, a checklist of known sources. Napoleon Bonaparte’s invasion of Egypt in 1798 and subsequent publications like the Description de l’Égypte introduced new monuments to Western artists, and in the late 19th century, archaeological finds provided further sources for jewellers, furniture designers and Orientalist artists. They then incorporated artefacts from museums into their art to lend authenticity. In the 1920s, the rediscovery of Tutankhamun’s treasures spawned a ‘Tutmania’ that touched all aspects of visual culture.

The continued use of ancient Egyptian imagery is more than just an aesthetic. It is a visual reflection of how ancient Egypt’s heritage has been contested and reinterpreted for different purposes. In Europe, for centuries, ancient Egypt was seen as part of Western history, not African. It was held as the origin of wisdom and law, and the precursor to classical civilisation. The great European powers of the 18th and 19th centuries saw themselves as heirs to Egypt’s legacy. It is no coincidence that artistic uses of ancient Egyptian imagery flourished at the same time they attempted to control Egypt. Similarly, the archaeological discoveries that were shipped to European museums and inspired Victorian artists were only possible because of ongoing European influence in Egypt. Each time Egypt appears in art, it tells us something about those reusing it. The Egyptianising aesthetic cannot be understood without highlighting the motivations underlying it.

Egypt’s own voice in this narrative has historically been ignored. The artistic story is told through a Western lens. Yet at each of the important moments explored in this exhibition, Egypt was also engaging with its pharaonic past through art. In the 1920s, a generation of Egyptian artists, trained in Europe, turned to pharaonic imagery to make powerful statements about Egyptian identity, nationalism and independence. More recently, Egyptian- Armenian artist Chant Avedissian has explored Egyptian motifs as part of a larger visual vocabulary linking societies across the Middle East and Asia. Visions of Ancient Egypt explores this little-known narrative, revealing how Egyptian artists have responded to Egypt’s pharaonic legacy. Here on these pages are just some of the treasures to be seen in the show.

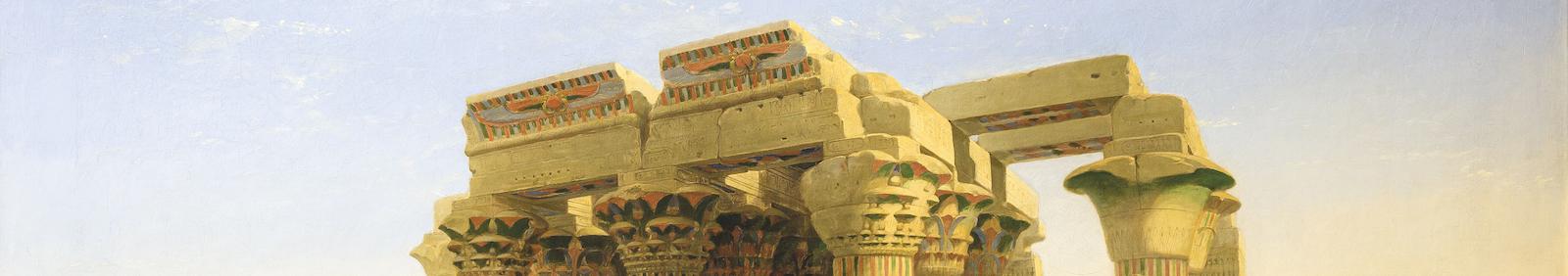

RUINS OF THE TEMPLE OF KOM OMBO (ABOVE)

David Roberts’ 1842–43 panorama of the temple at Kom Ombo represents a picturesque view, the architecture highlighted by a low sun and dwarfing the figures in the foreground. It shows how Roberts, who travelled to Egypt between 1838 and 1839, contributed to the romanticised vision of Egypt. He drew on his training as a theatre scene painter to create atmospheric settings, adding largely imaginary groups of figures to emphasise scale and the scene’s exoticism.

The Fourth Pyramid Belongs to Her, Sara Sallam, 2016-18

THE FOURTH PYRAMID BELONGS TO HER

This 2016–18 collage is part of a series in which artist Sara Sallam explores Egyptians’ attitudes to their ancient past. She explains: ‘To accentuate the absence of collective mourning for the ancient Egyptians, I portray my grandmother as one of the pharaohs in a series of collage portraits, projecting, in turn, my personal grieving for her onto them. In doing so, this project becomes an invitation to reacknowledge their forgotten humanity and to see them through the eyes of a girl mourning her grandmother.’

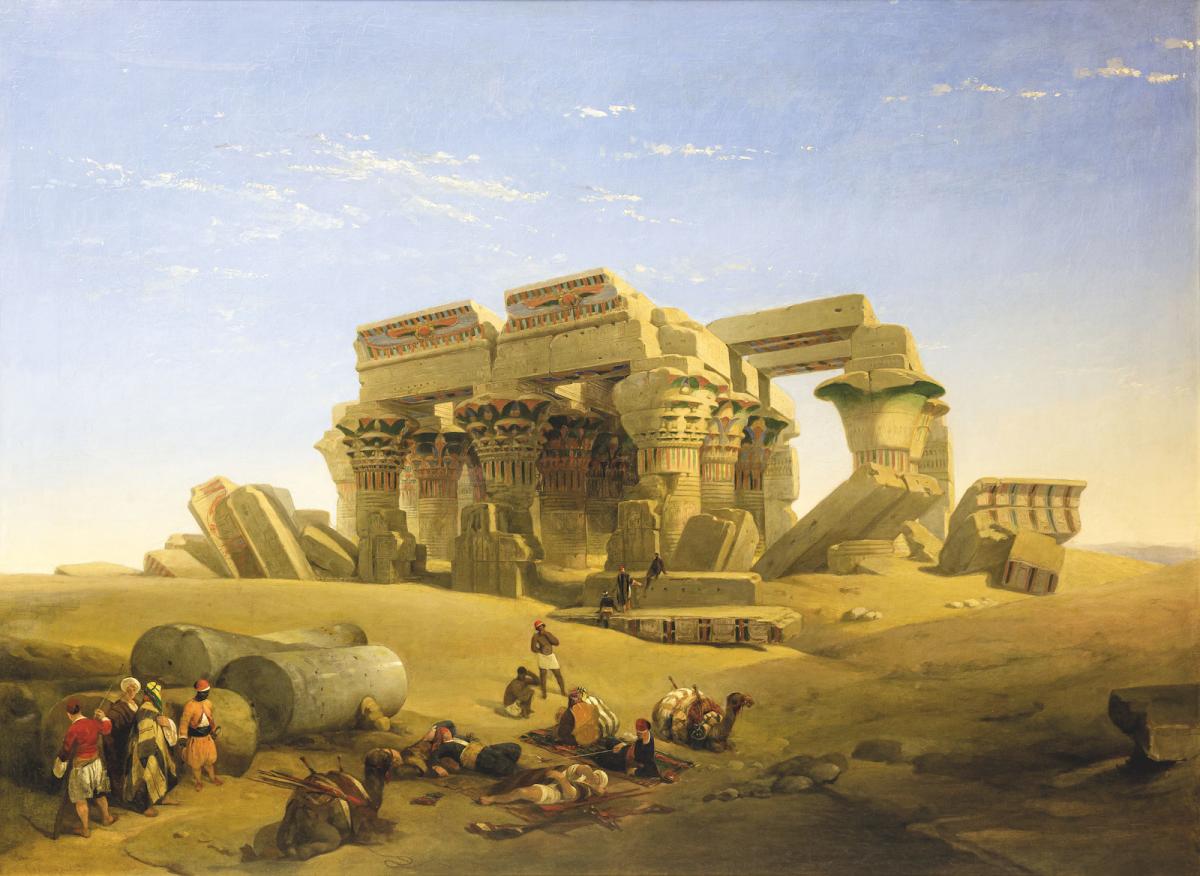

Nefertiti (Black Power), Awol Erizku, 2018

NEFERTITI (BLACK POWER)

This 2018 neon work by Ethiopian-American artist Awol Erizku reclaims the Egyptian queen as specifically African royalty, and as a powerful symbol of African-American pride and empowerment. Erizku weaves together African, East Asian and North American cultural references, bringing together an African queen with Chinese characters reading ‘black power’, to address issues of race, identity and politics.

Pastime in Ancient Egypt, Lawrence Alma-Tadema, 1864

PASTIME IN ANCIENT EGYPT

In his 1863 painting, Lawrence Alma-Tadema transformed the visual representation of ancient Egypt. Departing from previous evocations of sparsely inhabited ruins, he imagined an animated, vibrant scene. Here he drew on archaeological publications and recently excavated objects displayed in national museums; details like the furniture and instruments were painstakingly copied from real examples. The work is a vision of pharaonic Egypt combining drama, exoticism and eroticism, but also archaeological accuracy, lending ‘realism’ to an otherwise fanciful scene.

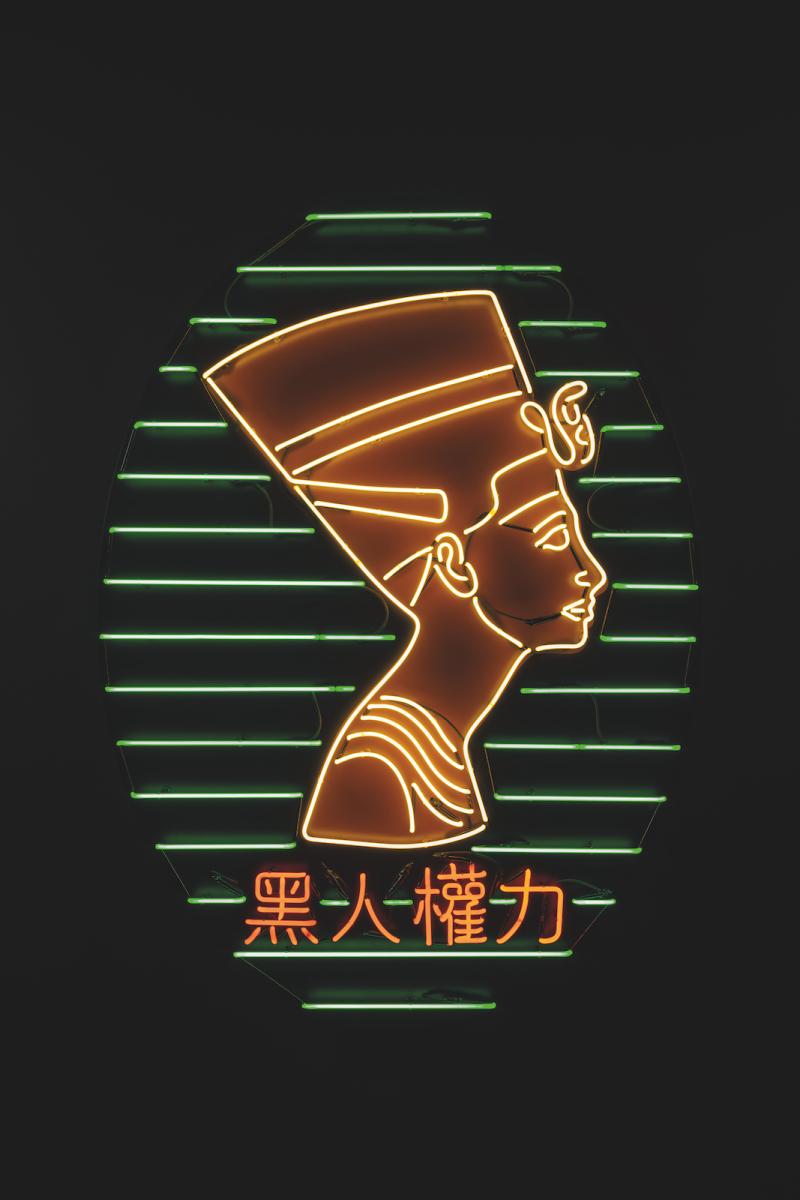

Alberto Giacometti’s Standing Woman, 1958–9

STANDING WOMAN

Alberto Giacometti’s 1958–9 Standing Woman betrays his fascination with ancient Egyptian sculpture. Depicting a figure in frontal pose with its arms along its sides and placed on a block-like base, it speaks directly to ancient statuettes. Modernist artists like Giacometti turned to Egyptian art as one of a range of non-Western sources, countering the traditional ‘canonical’ sources of classical Greek and Roman art. For Giacometti, ancient Egyptian art represented reality more closely than Western art since the Renaissance.

WEDGWOOD’S CANOPIC JAR

Wedgwood was an early proponent of the Egyptian style, yet his source material for designs was second-hand, derived from prints that illustrated Egyptian and Roman-era Egyptianising objects in Italy. His 1790 ‘Canopic Jar’ typifies the dissemination of ideas: its design is copied from a print, which itself illustrated a Roman Egyptianising artefact mistakenly believed to be Egyptian. At this time, Egyptian art was seen through a distorting classical lens, and print sources were crucial in spreading images of Egypt across Europe.

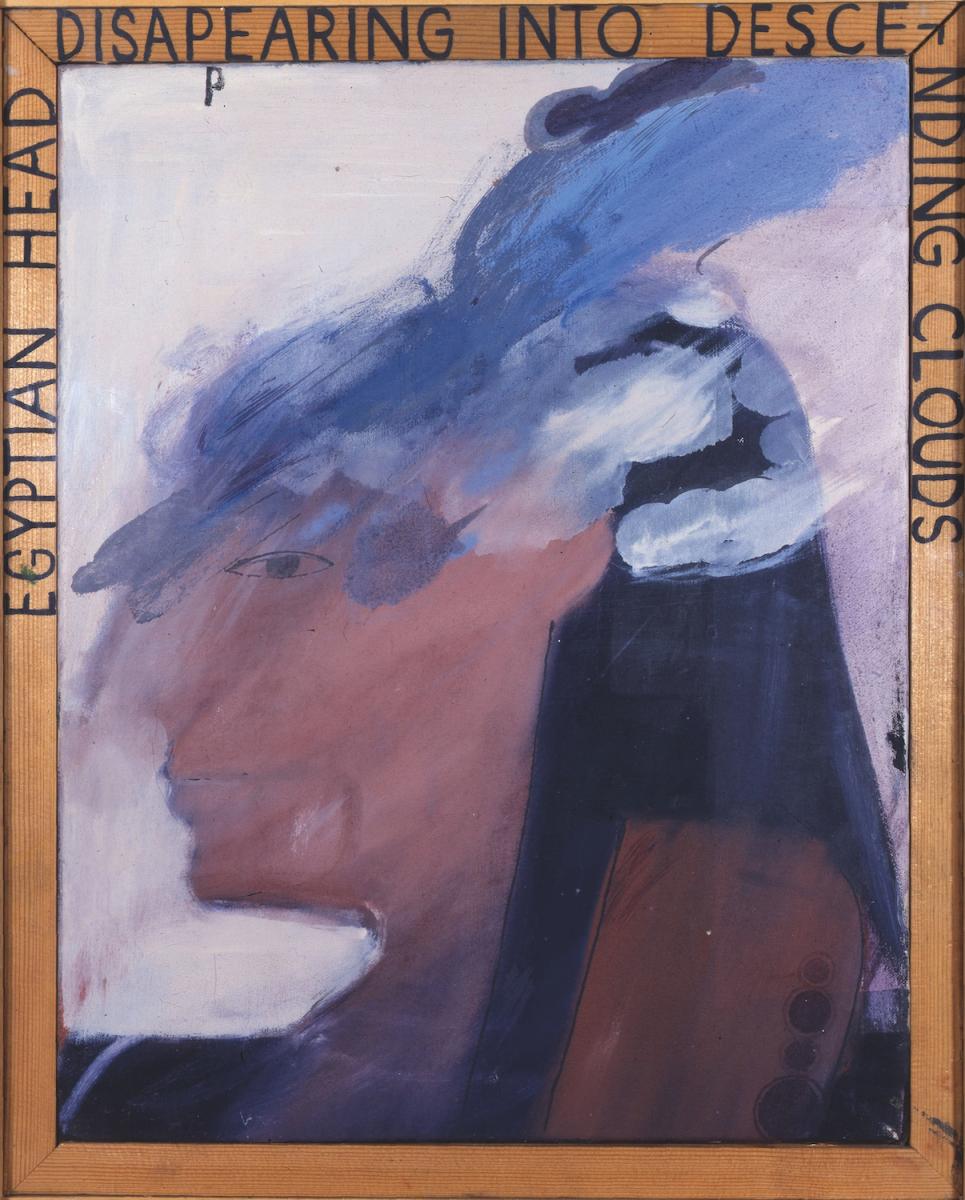

Egyptian Head Disappearing into Descending Clouds, David Hockney, 1961

EGYPTIAN HEAD DISAPPEARING INTO DESCENDING CLOUDS

David Hockney executed this painting in 1961, while a student at the Royal College of Art and before he first visited Egypt in 1963, showing his long- standing interest in ancient Egyptian art. The close-up of an Egyptian head in a distinctive profile, partly obscured by a painterly cloud that disrupts the head’s flatness, suggests his playful attitude towards the formal qualities of ancient Egyptian art.

IMAGE CREDITS: © ROCHDALE ARTS & HERITAGE SERVICE.VCOURTESY OF THE ARTIST AND TINTERA GALLERY; © HARRIS MUSEUM & ART GALLERY; © THE ARTIST, COURTESY BEN BROWN FINE ARTS; SAINSBURY CENTRE COLLECTION © ALBERTO GIACOMETTI ESTATE. © YORK MUSEUMS TRUST (YORK ART GALLERY); JOSIAH WEDGWOOD & SONS/1790 © VICTORIA AND ALBERT MUSEUM, LONDON

SEE

Visions of Ancient Egypt (supported by Viking), The Sainsbury Centre, Norwich

3 September 2022–1 January 2023

sainsburycentre.ac.uk

About the Author

Dr Benjamin Hinson and Dr Anna Ferrari

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition