This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

How the artist Mondrian went from trees to triangles

How the artist Mondrian went from trees to triangles

30 Sep 2022

It is 150 years since the pioneering artist Piet Mondrian was born. Today we associate him with bold abstract works yet, says Chloë Ashby, look at his early art and you’ll discover a whole new Mondrian

Woods near Oele, 1908. Credit: Kunstmuseum Den Haag, The Hague, The Netherlands, Salomon B Slijper Bequest © 2021 Mondrian/Holtzman Trust

Piet Mondrian was born in the Dutch town of Amersfoort in 1872. His father, a headmaster and keen amateur artist, gave him drawing lessons, and his Uncle Fritz introduced him to the Impressionistic style of the Hague School.

Mondrian went on to qualify as an art teacher and, aged 20, he enrolled at the Rijksakademie van Beeldende Kunsten in Amsterdam. During three years of academic training, he learned to draw from the model and practised copying old masters.

Up to the turn of the century, Mondrian produced the kind of landscapes that proved popular in the local art market: flowers and windmills, farmhouses and canals, seascapes and dunes. And yet, as important to him as the subject matter were colour and form, from the lemony orb of a sun to a tree’s whirling branches. There was a Romanticism to the way he traced the effects of natural light. His was a unique kind of realism.

Mill in Sunlight, painted in 1908. Credit: Kunstmuseum Den Haag, The Hague, The Netherlands, Salomon B Slijper Bequest/Restored with financial support from American Express/© 2021 Mondrian/Holtzman Trust

Mill in Sunlight, painted in 1908. Credit: Kunstmuseum Den Haag, The Hague, The Netherlands, Salomon B Slijper Bequest/Restored with financial support from American Express/© 2021 Mondrian/Holtzman Trust

New hues and views

It’s unclear when exactly that realism began to give way to abstraction, but gradually Mondrian replaced the earthy tones of 19th-century Dutch landscape paintings with expressive and saturated hues.

He took inspiration from the Impressionists and the Fauves, and the Symbolist paintings of Vincent

van Gogh, whose exhibition he visited in Amsterdam in 1905. He was also influenced by spiritualist movements such as Theosophy, which placed an emphasis on mystical experience.

Mill in Sunlight (1908), a highlight at the current Fondation Beyeler exhibition Mondrian Evolution (on until 9 October) shows a windmill blazing red against a shimmering, speckled sky. Rendered with coarse brushstrokes, the field looks like it’s been freshly ploughed. There may be a pool of water glistening with reflections in front of the wooden structure, or it could simply be a mirage. Across the canvas are glinting lines and cross-hatchings, a hint of the rectilinear arrangements to come.

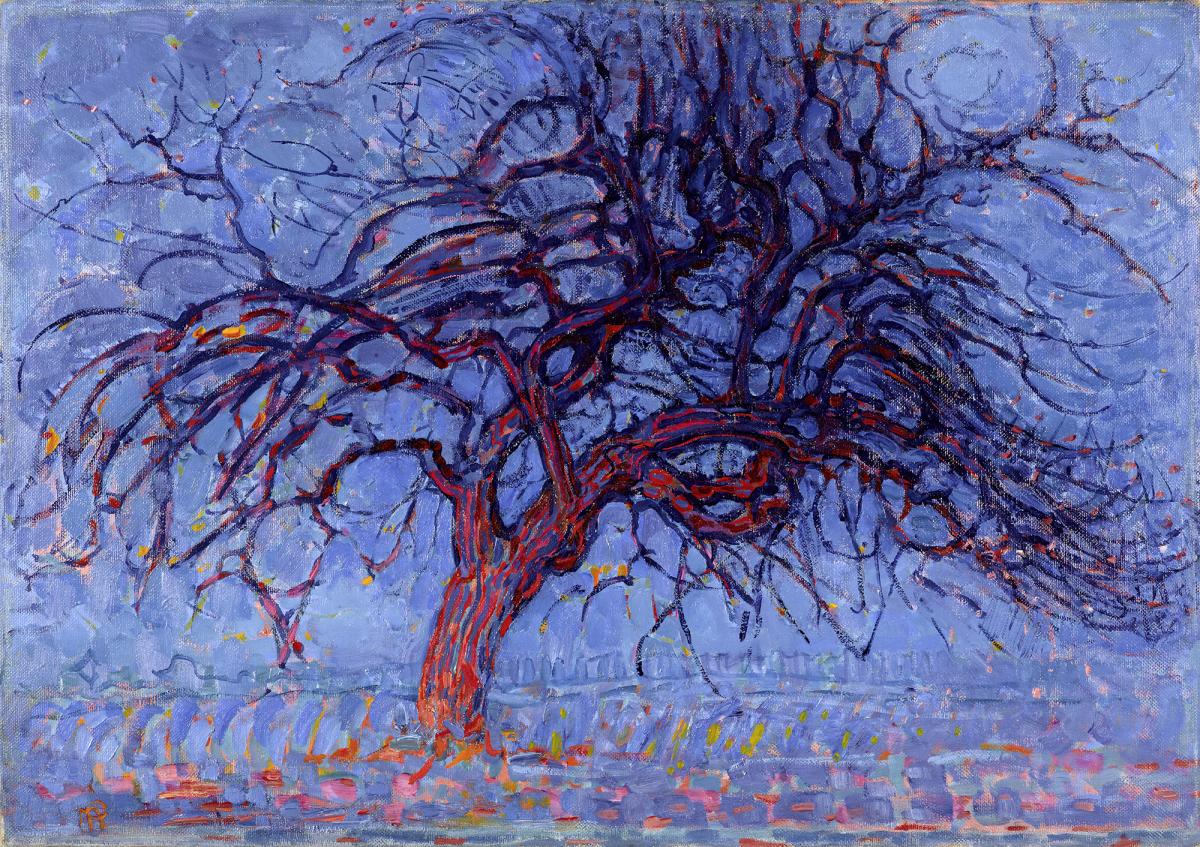

Evening: The Red Tree, 1908–10. Credit: Kunstmuseum Den Haag, The Hague, The Netherlands © 2021 Mondrian/Holtzman Trust

Evening: The Red Tree, 1908–10. Credit: Kunstmuseum Den Haag, The Hague, The Netherlands © 2021 Mondrian/Holtzman Trust

Paris, Picasso and more

Energised by the Modern art emerging from Paris, which he glimpsed at another exhibition in Amsterdam in 1911, Mondrian decided to move there. For two years he absorbed the Cubist creations of Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, learning how to look beyond the outer appearance of things.

Going one step further, by 1914 he was painting his Pier and Ocean series, abstractions without volume, composed entirely of vertical and horizontal black lines. ‘I wish to approach truth as closely as is possible, and therefore I abstract everything until I arrive at the fundamental quality of objects,’ he said.

Back in the Netherlands, in 1917 he co-founded the Dutch art and design movement De Stijl with artist Theo van Doesburg, advocating an abstract style he called Neo-Plasticism.

Mondrian’s Composition with Yellow and Blue, 1932. Credit: Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Beyeler Collection, purchased with a donation by Hartmann P and Cécile Koechlin-Tanner, Riehen © Mondrian/Holtzman Trust. Photo: Robert Bayer, Basel

Mondrian’s Composition with Yellow and Blue, 1932. Credit: Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Beyeler Collection, purchased with a donation by Hartmann P and Cécile Koechlin-Tanner, Riehen © Mondrian/Holtzman Trust. Photo: Robert Bayer, Basel

Ideals and unity

Practitioners of Neo-Plasticism renounced realism in favour of pure and spiritual geometries that they believed could help restore balance after World War I. Theirs was a rational ideal comprised of long continuous lines and large windows of primary colours.

‘Mondrian understood abstraction as a process of approaching absolute truth and beauty, which he aspired to as an artist,’ says Ulf Küster, curator of Mondrian Evolution. ‘He carried out his stylistic development by searching for the unity and essence of the image itself.’

All minimalist aspects of modern design, says Küster, ‘have their starting point somewhere with Mondrian’. And yet, he was much more than a single-minded minimalist, a man committed to his principals. His early works – lush and varied, joyous and rich – attest to that.

Mondrian Evolution is at the Fondation Beyeler, Switzerland until 9 October; fondationbeyeler.ch

Find out more

Read the full feature in the summer issue of The Arts Society Magazine, available exclusively to members and supporters of The Arts Society (to join, see theartssociety.org/member-benefits)

About the Author

Chloë Ashby

Chloë Ashby is an arts writer and novelist; her latest novel is Wet Paint and her book Colours of Art: The Story of Art in 80 Palettes is out now

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition