This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

Five gold rings for the season

Five gold rings for the season

20 Dec 2022

Ciaran Sneddon selects five gold rings in the form of art – from saintly altar decorations to the most distant artwork ever created

December and January are a time of celebration for many of us, no matter which festivities we choose to honour.

It’s also a time of artistic frisson, with a multitude of songs, performances, exhibitions and other works devoted entirely to marking Yuletide.

Here, we look at five pieces that unwittingly support the crescendoing lyric of a Christmas carol classic – The Twelve Days of Christmas. Perhaps you will enjoy reflecting on them as choir sopranos belt out with gusto: ‘five golden rings’…

Circle of gold

Saint Alexander, by Fra Angelico (Guido di Pietro), c.1425. Credit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Bequest of Lucy G Moses, 1990

Saint Alexander, by Fra Angelico (Guido di Pietro), c.1425. Credit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Bequest of Lucy G Moses, 1990

Suitably saintly in both content and appearance, this early altar decoration from the church of San Domenico in Fiesole in Tuscany is a golden delight. Saint Alexander may not be the patron saint of anything, but he certainly holds a close association with gold, and is often depicted encircled by a halo of that colour.

Fra Angelico, meanwhile, was a driving force of the early Renaissance in Italy. This piece was made while Angelico served as friar of the church in which it was installed. His commitment to religion has earned him the nickname Beato Angelico (‘Blessed Angelic One’), and a proclamation by Pope John Paul II that he was indeed ‘blessed’.

A certain ring to it

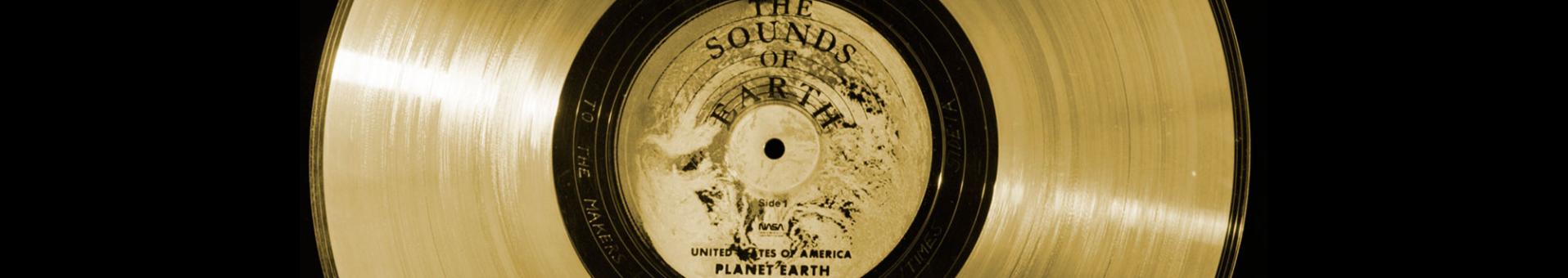

Voyager Golden Record, NASA, 1977. Credit: NASA’s Jet Propulsion Library, shared under a Creative Commons licence

They are the most distant-known artworks ever created by mankind.

Launched in 1977, the Golden Records onboard Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 are a noble attempt to summarise life on Earth to possible intelligent extraterrestrial life forms. Whether they will ever be appreciated by any other living things is unlikely: the best chance seems to be Voyager 1’s eventual pass within a relatively close distance of a star in around 40,000 years.

The contents of the records were determined by a committee. Among the final inclusions are audio clips of natural sounds, recorded greetings in 55 languages, messages from then-US President Carter and the UN Secretary General, music and 115 images. Some of these images are technical graphs that help give Earth’s home address, while others include portrayals of sport, architecture, food, music and human biology.

In the round

Helmet Crest (Maidate), by an unknown artist, 18th to 19th century. Credit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Bequest of George C Stone, 1935

Helmet Crest (Maidate), by an unknown artist, 18th to 19th century. Credit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Bequest of George C Stone, 1935

Golden rings are not the property of the Christian faith alone. Indeed, hollowed circles of the eye-catching colour are found the world over. This example is made of wood, lacquer, textile and gold, and is of Japanese origin.

It would have been mounted on the front of a helmet, and its central characters are a representation of the war god Hachiman. Then a Shintō deity, he was absorbed by Buddhism and renamed Daibosatsu. Though the exact use of this crest is unknown, the god was seen as a protective figure. Similar crests have been found that served different purposes. Some were a representation of family, others of religion, with iconography that varies from renderings of plants and animals to traditional heralds.

Halo rings

Madonna and Child, Berlinghiero (early 13th century, c.1230s). Credit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Gift of Irma N Straus, 1960

Madonna and Child, Berlinghiero (early 13th century, c.1230s). Credit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Gift of Irma N Straus, 1960

This is one of just two pieces to be definitively assigned to the artist Berlinghiero, who was one of Tuscany’s most prominent artists of the time. It is Byzantine in nature, and familiar to those with even the slightest level of interest or knowledge of this style. The all-gold background is typical, and though the two figures may be fairly simply depicted, there are a few clear physical metaphors.

Jesus, whose halo is intersected with a crucifix, holds a scroll that identifies him as a source of great knowledge. His outfit would also not look astray on the body of a philosopher. His mother, meanwhile, indicates her son – pointing the way to the future and to salvation.

Solar circle

Glass positive photograph of total solar eclipse, Royal Observatory, Greenwich, 1919. Credit: Science Museum Group/in accordance with Creative Commons licence

Glass positive photograph of total solar eclipse, Royal Observatory, Greenwich, 1919. Credit: Science Museum Group/in accordance with Creative Commons licence

A halo of a different kind, and art of space rather than in space, this early image shows the corona at the central moment of a solar eclipse.

Captured on 29 May 1919 in Sobral, Brazil by Sir Arthur Eddington on behalf of the Royal Observatory, it was part of a project to assess Einstein’s theory of relativity.

Science aside, the sun has clearly been a key inspiration and focus for artists since the literal dawn of humanity. As technological advances were made, and mankind leapt forward in its understanding of our place in the universe, more traditional depictions of Earth’s closest star gave way to photography and videography that represent its true form.

About the Author

Ciaran Sneddon

Ciaran Sneddon writes for The Arts Society

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition