This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

5 spooky artworks for Halloween

5 spooky artworks for Halloween

28 Oct 2022

The desire for eerie entertainment has not always been so attached to late October – it has always existed. Artists the world over have found inspiration, and success, in the macabre. Ciaran Sneddon uncovers the spooky remains of five artworks, each revealing a different tale of gloom, despair or fear

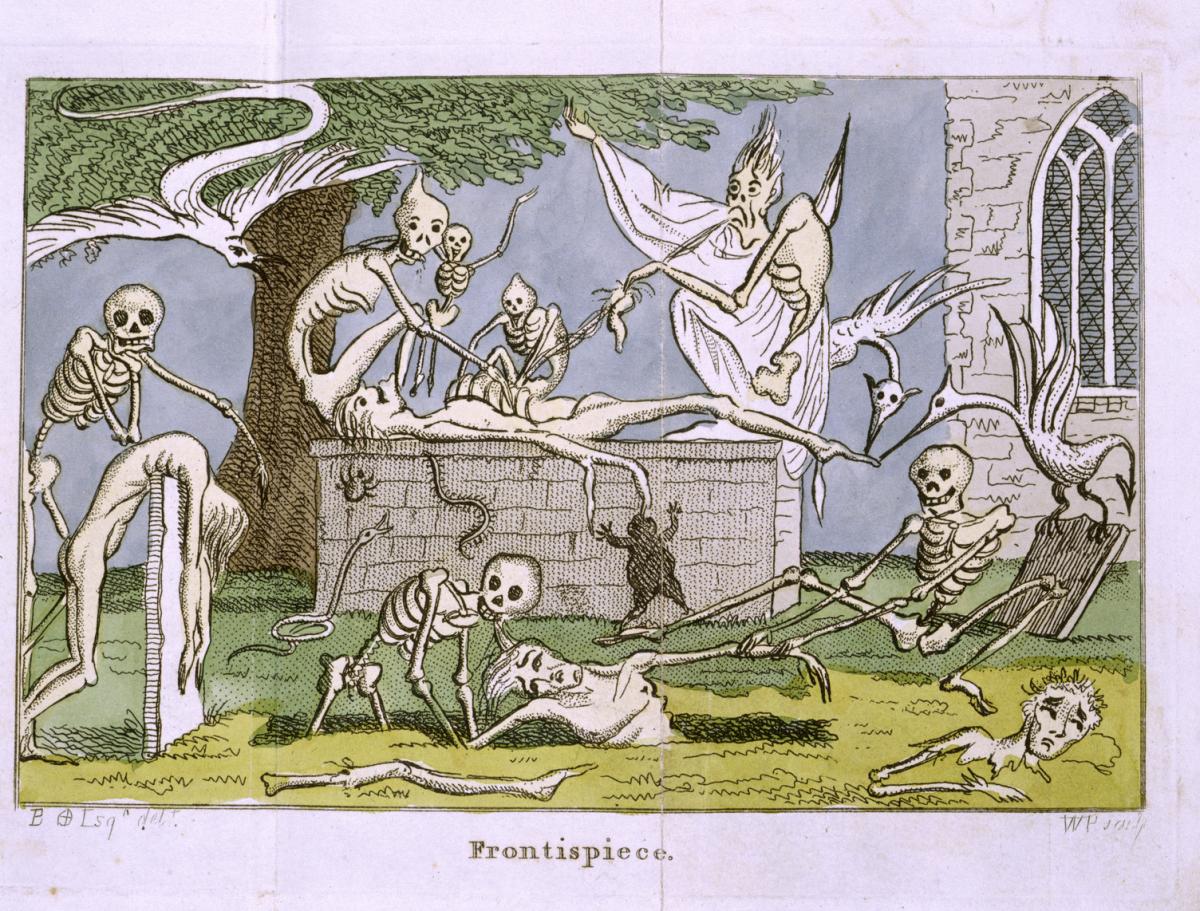

A frontispiece by an unknown artist from Tales of Terror, with an introductory dialogue, in the collection of the British Library. Credit: Flickr/British Library

A frontispiece by an unknown artist from Tales of Terror, with an introductory dialogue, in the collection of the British Library. Credit: Flickr/British Library

After dark…

Alone, the skeletons look almost comical: Casper-like apparitions from a children’s film. But the disembodied corpses, dragged from their graves and feasted upon by supernatural monsters, tell a different story. Or, perhaps, several stories. For this is the frontispiece of an early 19th-century work, supposedly by Gothic novelist MG ‘Monk’ Lewis, entitled Tales of Terror. Its grim fables are as colourful as the opening image, although this is mostly because it is a parody of a previous publication. This follow-up is a send-up of Lewis’ style and that of other contemporaries, including Sir Walter Scott. The frontispiece’s creator is unknown, but it was printed for R Faulder in 1808.

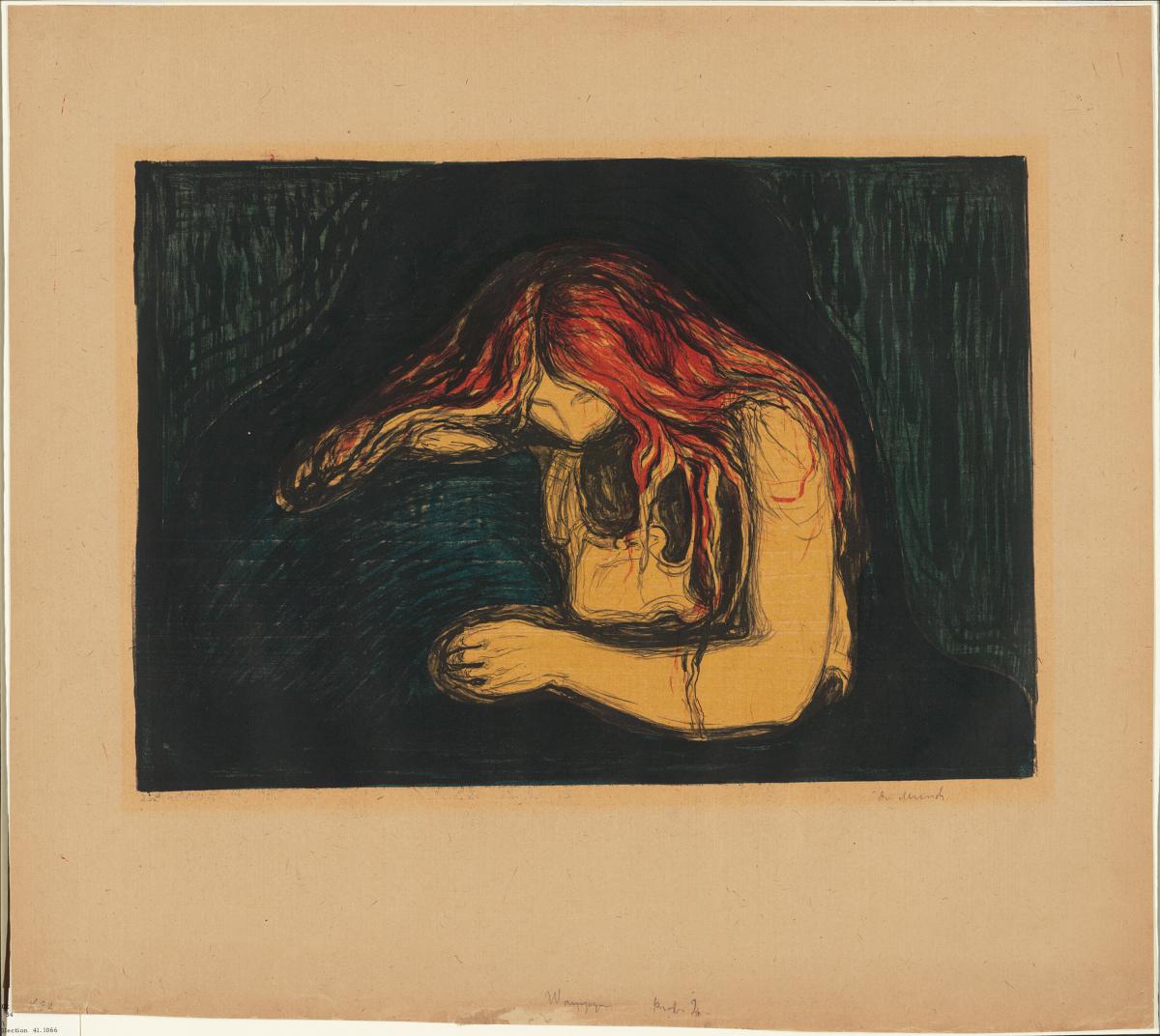

Vampire II, 1895–1902, by Edvard Munch. Credit: John H Wrenn Memorial Collection/Art Institute Chicago

A tender vampire?

A vampire it may be, but this piece’s name is a zombie: the second incarnation of a creature, unexpectedly brought to life. Munch (1863–1944), the artist who also brought us, of course, The Scream, had titled the shadowed figure Love and Pain, and it was by this name that it was exhibited in 1893. Poet and novelist Stanislaw Przybyszewski – a friend of Munch – felt this was a misnomer. Where Munch had seen a soft moment of a woman kissing and comforting a man, Przybyszewski saw a vampiric horror: a Gothic tale of temptation, deception and murder. In its new form, Vampire became a central theme of Munch’s work, with various iterations produced throughout the rest of his career.

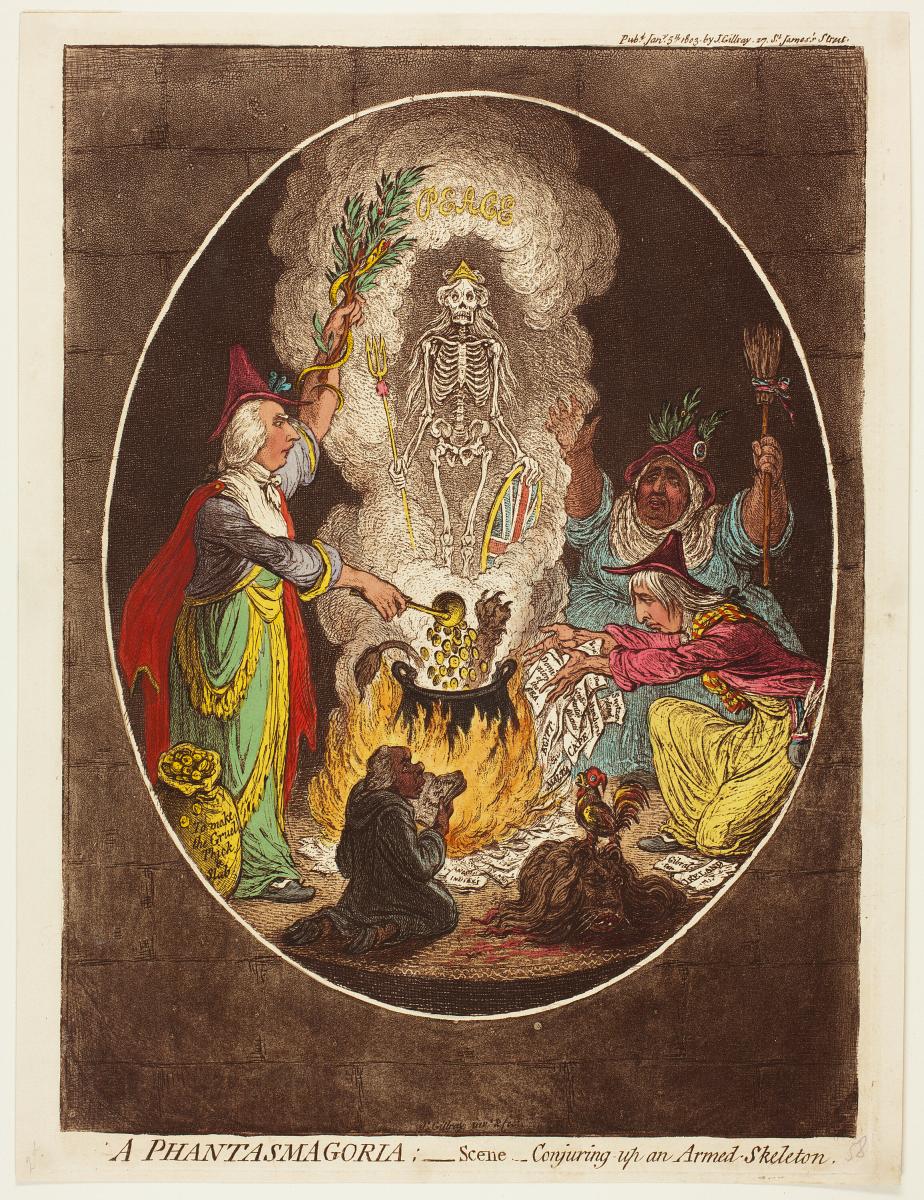

A Phantasmagoria – Scene – Conjuring Up an Armed Skeleton, by James Gillray, 1803. Credit: Gift of Thomas F Furness in memory of William McCallin McKee/Art Institute Chicago

A Phantasmagoria – Scene – Conjuring Up an Armed Skeleton, by James Gillray, 1803. Credit: Gift of Thomas F Furness in memory of William McCallin McKee/Art Institute Chicago

Conjuring spirits

An enduring idea of supernatural horror is that it can be used to highlight narratives and themes from the real world. So it was with this print by caricaturist James Gillray (1756–1815), who in this work returned to the then topical issue of the 1802 Treaty of Amiens – the agreement between France and the UK that saw the French Republic officially recognised by the British for the first time. Gillray was no fan of this arrangement, feeling that his country had been fooled by its former enemy, and that it was only a matter of time before Napoleon broke his side of the deal. Here he transports Shakespeare’s witches – recasting them in the shape of three proponents of the treaty – into a more modern age, where they encourage the British government to give up money and claims to colonised lands, in return for a creepy, skinned version of Britannia and a smoky apparition of peace.

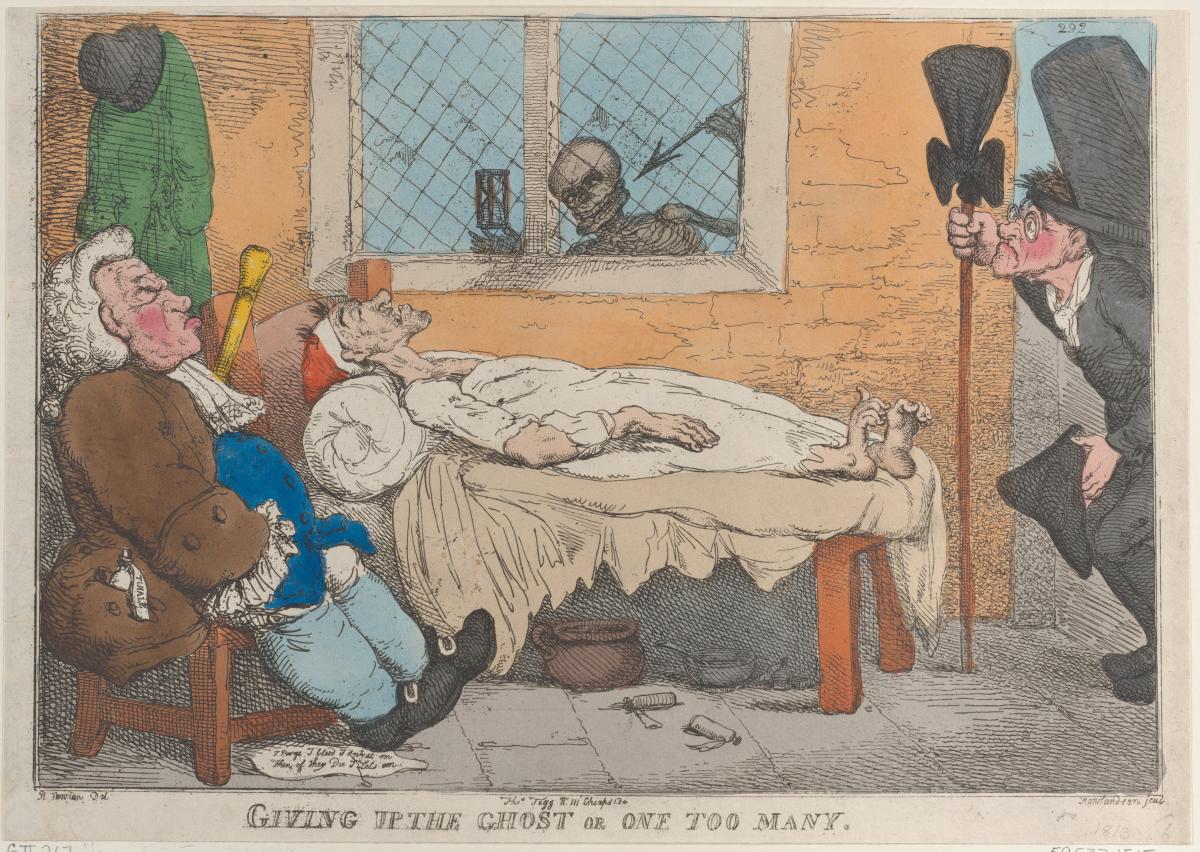

Giving Up the Ghost or One Too Many, by Thomas Rowlandson, c.1809. Credit: The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund,1959/The Met

Giving Up the Ghost or One Too Many, by Thomas Rowlandson, c.1809. Credit: The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund,1959/The Met

Ghoulish scenes

There is scathing satire etched into every stroke of this piece, pockmarked as it is with morbid detail and witty asides. The eye is naturally drawn to the grimacing skeleton – a representation of Death, clearly aware of his imminent duties here – but there is fun to be found elsewhere. There is the note beneath the physician’s chair that reads: ‘I purge, I bleed, I sweat em, then if they die, I lets em.’ The strewn bottles reveal Rowlandson’s long-standing interest in caricaturing the medical profession, usually as the target of humour. Of course, more horror may lie in Rowlandson’s erotica, which he created for private buyers. However, as that body of work was kept away from the public eye and has never fully resurfaced, it’s impossible to tell.

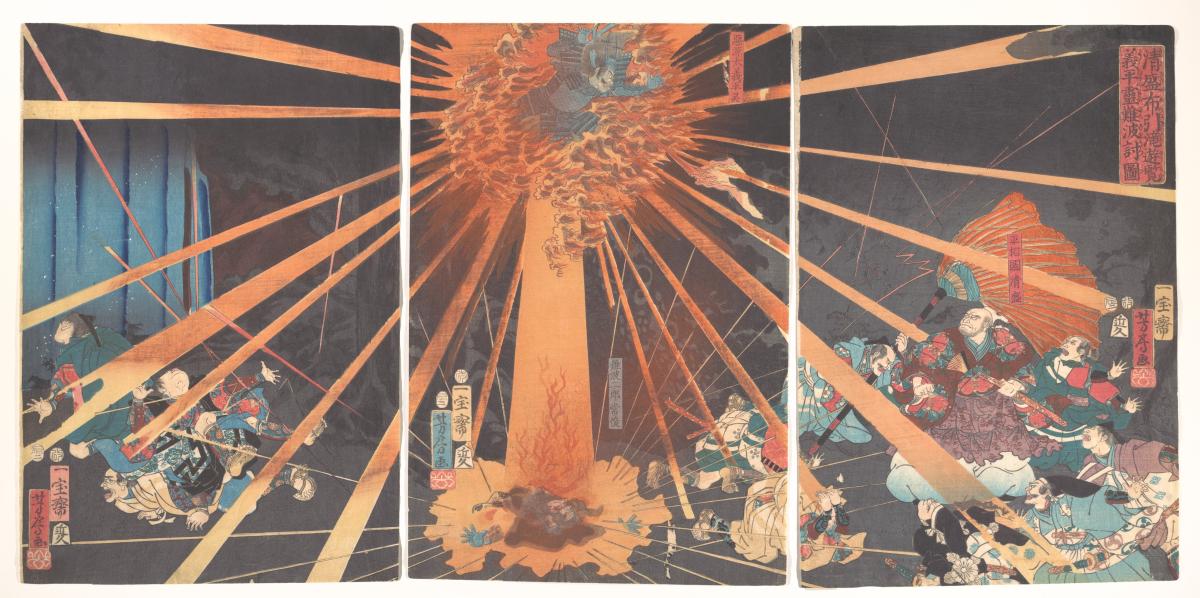

The Ghost of Akugenta Taking Revenge on Nanba at the Nunobiki Waterfall, by Utagawa Yoshifusa, 1856. Credit: Purchase, Arnold Weinstein Gift, 2001/The Met

The Ghost of Akugenta Taking Revenge on Nanba at the Nunobiki Waterfall, by Utagawa Yoshifusa, 1856. Credit: Purchase, Arnold Weinstein Gift, 2001/The Met

Rays of orange dissect the black and blue backdrop in this mythological scene, based on the Tale of Heiji. The tale is a 36-chapter-long war epic that details the Heiji Rebellion of the mid-12th century in Japan, albeit in a fashion that has snowballed over centuries of oral retellings. Yoshifusa’s trio of woodblock prints captures just one moment from the saga: the resurrected ghost of a warrior called Akugenta Yoshihira delighting in his moment of vengeance against his murderer, Nanba Jirō. This fearsome piece isn’t atypical of Yoshifusa’s portfolio. He built his name by presenting legendary heroes in unadulterated splendour, marking a conscious and significant change from the peaceful romanticism that had dominated the Japanese art world during his younger years.

About the Author

Ciaran Sneddon

Ciaran Sneddon writes for The Arts Society

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition